Tim Dunn: 'A railway engine, steam ones in particular, are probably the closest we’ve ever come to creating artificial life'

The Trainspotting Live presenter reveals how rail has become a way of life...

Talk to any driver or any person who’s ridden on a steam locomotive footplate... these things feel alive. They have personalities.Tim Dunn

Hello there! I thought I'd just explain what on earth I'm doing being a co-presenter on BBC Trainspotting Live. In my spare (!) time away from my main marketing job, I’m a railway historian, enthusiast, writer, curator and consultant to a number of railway-related museums and attractions in Britain and abroad: you could say that I quite like trains. But I claim that it’s not my fault; I claim that these things tend to find you. Nurture, perhaps, rather than nature.

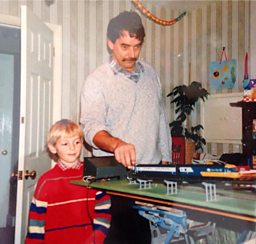

As a small Timmy I was brought up playing with model trains, learning how to read with a thousand of my grandfather’s railway books informing both my world view and my vocabulary. It didn’t help having a dad who had a fondness for railways too; he’d been a trainspotter as a kid in the early 60s. So, with dad’s help, being taken to see Intercity 125s whoosh past in Berkshire and then happily chat our way on to footplates on preserved steam railways every bank holiday, I wanted more. More of the most marvellous things: simple joys, delight in the perceived mundane but a constant desire to try to show others how brilliant those things were.

As I grew up, my train sets just got bigger. I did talks at school; I remember setting up a train set around the classroom where I and my classmates raced our Hornby Flying Scotsmans, Smokey Joes and those 125s. I had birthday parties in an old New York Subway car in Buckinghamshire and we took friends for rides on miniature trains. I then got paid to help run Bekonscot, the world's oldest model village; and there they have Britain’s biggest public model railway. I had the best job any railway-loving teenager could ever want.

I was never worried about the possibility of being bullied or having the mickey taken out of me for my love of railways, the technology that made them function or the places that resulted from them. Probably because I’ve always just enjoyed myself, and seen my hobby as a starting point for socialising, or sharing, or having fun. And I still do.

Because the joy of railways – not trains per se – is that they’re enablers. They’re the catalyst for something else. They connect; they join; they spark; they bring people together or make things happen. Grandpa’s railway books (and all of the ones I’ve acquired since) taught me about the world in which I live and they explained why the people were where they were, and why those people did what they did. Britain, like much of the modern world, has been shaped by transport: and much of that is down to the railways. And that’s why I’m happy to have a little part to play on BBC Trainspotting Live, because I’m pleased to be able to share some of my enthusiasm and a few of the facts that I’ve picked up on the way.

Perhaps it’s also because a railway engine, steam ones in particular, are probably the closest we’ve ever come to creating artificial life. They’re elemental. Forget Frankenstein’s monster: talk to any driver or any person who’s ridden on a steam locomotive footplate or stood next to one in repose as steam gently whiffles from a valve: these things feel alive. They have personalities. Created from steel and iron, hacked from beneath our feet by men in times past, these creatures are fed by coal made from ancient life, watered from rain from the sky and lit from a burning flame. These things come together to create new life – a movement, a breathing, oscillating machine that responds to its environment. And like a real creature, when we see one in danger, or when it is hurt, railway enthusiasts run to save it, to help it, to repair it; like a pet seeing a surgeon. No surprise that so many vicars (male and female) delight in railway enthusiasm – perhaps they too, see man’s creation of a steam engine to be something theologically important.

Or perhaps I’m taking it all a bit too seriously. After all, I generally see a train as a chance to visit a pub with an ever-changing view.

Like any pastime, sometimes enthusiasm switches to obsession: the key of course, is to know when to stop. And you only know when to stop when you have self-awareness. Perhaps finding myself as a co-presenter on a BBC programme called Trainspotting Live is my clue to stop; or perhaps it’s a clue that I’m not quite ready to.

I don’t think I am ready to stop tracking down the remarkable iron horses, mechanical marvels and rusting dinosaurs of the railway age. Whether it’s finding myself on the team helping to bring the Postal Museum’s Mail Rail system underneath London to a wider audience, writing for the London Transport Museum blog, or whether it’s being a trustee of an incredible and quite beautiful project to help an Ebola crisis-beating Sierra Leone National Railway Museum transform lives in West Africa using old British-built trains, I think I’m on the right track. And I’m chuffed to bits to have people riding along with me.