Our theatrical past laid bare

By Adrian Edwards, Curator, the British Library

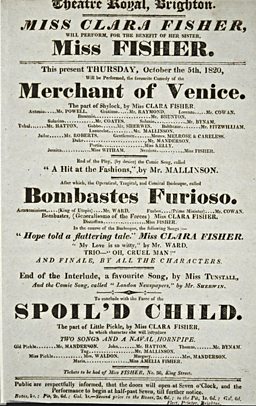

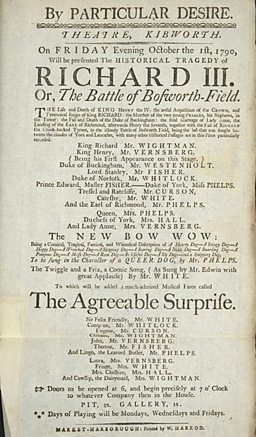

In the days before breakfast and drivetime programmes, with no chat shows or peer-to-peer review websites, it was the humble printed playbill, often trumpeting bold claims and superlative language, which was used to attract an audience to its seats.

Hundreds of years after their primary purpose has passed, they now act as a mouth-watering record of performance across the country, painting a comprehensive picture of Britain's theatrical past. The extensive collection of playbills in the British Library date from 1753 to the early years of the 20th century and cover cities and towns, villages and hamlets: from Stratford-upon-Avon to Southam.

They are not posters – the playbills used the letter press, not the technology of mass production.

These are fliers or bills advertising performances, printed by local printers to be distributed, put up and given out to entice audiences along to the shows. They were also for use during the performance itself to find out who was on stage next, like a theatre programme today. They are not posters – the playbills used the letter press, not the technology of mass production.

Playbills don’t have illustrations (other than a printer’s standard decorative ornaments), but the language used to advertise each performance can offer insights into details such as the performance venue, how the company promoted themselves and the price of seats! Some were produced for travelling theatre companies and these leave blanks in place of dates or venues.

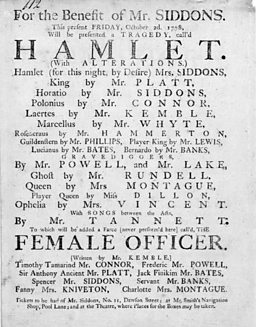

Othello, Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard II, Richard III, The Merchant of Venice and Romeo and Juliet are the Shakespeare plays that crop up most often. But if we were to watch these plays we may be surprised to see how they had been adapted to suit changing tastes, from adding new characters or songs to changing the ending!

This was particularly true when it came to performances out of London where, far from the eye of the critics and academics, there was more freedom to interpret Shakespeare’s work. Companies sometimes experimented by staging different versions of his work in the regions or 'provinces' as they were called at the time. It meant actors were also freer to experiment – such as the actress Sarah Siddons who played Hamlet on a limited number of occasions and only in the regions. We have a rare playbill for one of her performances in Liverpool dated 1778.

There are sketches, living tableaux and plays where Shakespeare appears as a character.

There are sketches, living tableaux and plays where Shakespeare appears as a character. There are also a number of pageants in honour of the Bard, and a play known as The Jubilee which was sparked by the first national event to honour the bard in 1769, organised by the actor-manager and adaptor, David Garrick.

Unlike today, Shakespeare tends to be part of a programme of entertainment which could include songs, farce, burlesques and plays by other dramatists. And he’s not always top of the bill – sometimes his work is performed as an afterpiece!

So sit back in your seat in the stalls and enjoy a cornucopia of Shakespeare, burlesques melodrama, historical epics and amateur productions. The cast includes some of the greatest actors and managers of their day from the Kembles, Macready, Kean, Henry Irving and Bram Stoker of Dracula fame. Then there’s the women who performed in the 18th and 19th centuries: Sarah Siddons, Charlotte Cushman, Ellen Terry and others. Also, the child stars such as the infant Kean, the Young Roscius (a term applied to actors of all ages), and Clara Fisher. There was the first black Othello – Ira Aldridge – an American actor who successfully toured the regions from the mid 1820s onwards.

We hope you enjoy their stories!

![]()

Shakespeare Lives

The nation’s greatest performing arts institutions mark 400 years since the Bard's death

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

About Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

What do playbills reveal?

- They inform us where tours of different areas took place – we have information relating to Ira Aldridge’s tour across the East and South East of England, for example…

- Benefit performances –charities, local businessmen, actors and theatre managers usually got one benefits night, usually at the end of a season where they chose the play and got all profits after running costs and salaries etc…

- How these works were performed – with beautiful scenery, new gas lighting, costumes andspecial effects…

- The locality at the time – for example, was it a small town? Was it popular with travellers? And what about a growing population due to the industrial revolution?...

- What was on the bill with Shakespeare? A farce coupled with a Shakespearean tragedy perhaps?...

- Why was Shakespeare performed in this location? Was there an established theatre, was it a stopping point at the back of a pub for travellers in need of entertainment, or was the performance part of an event such as a festival or fair?

- They can also tell us something about the economic prosperity of an area, and the demand for entertainment.

A few are also a commentary on historical events of the time, such as the political burlesques which satirised well known performances and relied upon the audience being in on the joke. For example, in London during the protests about the Corn Laws there were productions of The Tempest which featured Ariel as a law enforcement officer.

The playbills can also offer a commentary on the times and suggest the growth of a particular city due to the industrial revolution, or ease of access due to the railways, or the introduction of technologies such as gas lighting.

As theatres were built they can also tell a story of the local businessmen or theatre impresarios who put their money into creating these new palaces of entertainment.

This is the first time a collection has been explored in such a way – academics are in the process of researching this subject.

So it’s an exciting opportunity to tell original stories, offer fresh insight into Shakespeare, his works, his audiences and the places featured on the playbills.

Related Links

![]()

Who can we thank for Shakespeare's popularity?

The David Garrick Effect

![]()

Was Shakespeare a genius?

Where did the term 'bardolatry' come from?

![]()

The first lady of Shakespeare

Sarah Siddons helped legitimise the role of female performers

![]()

The actor who overcame prejudice to win over audiences

Ira Aldridge toured extensively during the 19th Century