Frederick Ashton: virtuoso

Deborah Bull on English ballet's master choreographer

Dancer, writer and broadcaster Deborah Bull spent twenty years with The Royal Ballet. She first met Sir Frederick Ashton in 1980 when he gave a talk to the students of The Royal Ballet School and the retired legendary choreographer was a frequent visitor to the company's rehearsal studios.

On the eve of a season of Ashton's finest works at the Royal Ballet, Deborah writes for BBC Arts on his life and work.

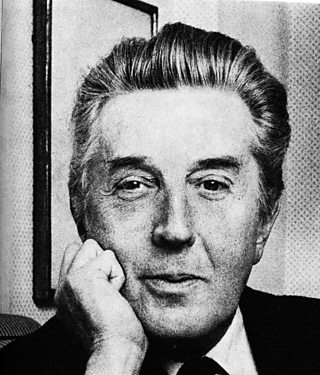

Frederick Ashton

In 1917 in a theatre in Lima, Peru, the 13 year-old Frederick Ashton witnessed a performance by the celebrated Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova. He was smitten, forever. 'She injected me with her poison', he would later say, and her precisely schooled classicism combined with subtle glamour and expressive lyricism became the touchstone of the English Ballet style he would go on to create.

My first memory of Fred is some 63 years later and a talk he gave while I was a student at The Royal Ballet School. At the end, I put up my hand to ask a question:

"What do you do if you're creating a ballet and you realize that the dancer you've cast is not, after all, right for the role?"

"My dear", he replied, as if I should have known, "you can't break someone's heart".

It's not a question he ever had to consider, where I was concerned.

By the time I joined The Royal Ballet in 1981, Ashton had been retired for a decade and besides, I was never really a 'Fred' dancer. His eye always went to artists with lyricism and softer charm; my style was athletic and highly physical.

Despite his retirement, he was a frequent presence in the company's rehearsal studios in West London's Barons Court, still dapper and distinguished, wreathed in cigarette smoke and relishing his status as the elder statesman of ballet.

In his eighties by now, he still had a ballet left in him (Varii Capricci, 1983) and plenty of wisdom to impart.

As a member of the corps de ballet, you find yourself dancing in most of the repertoire, regardless of your style and choreographers' preferences. So early on, I was cast in the work that was – perhaps surprisingly – his own favourite from amongst all his ballets, the 1948 Scènes de Ballet.

Superficially, it's a cool and cosmopolitan work without a plot that perhaps evokes the lost, fashionable demi-monde of the thirties. But its underlying architecture is based on Euclidian geometry – an interest Ashton developed during his wartime service in the RAF, where he was responsible for analysing aerial photographs.

Post-war, he applied these patterns in the dance studio, producing a fascinating work that can, allegedly, be viewed satisfactorily from any angle.

This rigour makes for a work that is as engaging to dance as it is to watch. Unusually for Fred, who was typically drawn to highly melodic and rhythmic music, it is set to a score by Stravinsky that isn't entirely regular and lacks obvious lyricism.

In the corps de ballet we synchronised our steps not by the usual technique of counting, but by humming under our breath the music's asymmetric and complex phrases. I can still sing them now.

I began to dance the Winter Fairy in Cinderella not long before Ashton's death in 1988 and its icy choreography marked a slight thaw in the choreographer's regard for me and my work. It's a fiendishly difficult solo, originally created for Beryl Grey 40 years earlier.

But like much of Cinderella, it is Ashton at his best: every step reveals something about the character who dances it, proving that movement can, in the hands of a master, be more evocative than words.

It's impossible to write about Fred without evoking the memory of Margot Fonteyn, the ballerina through whose artistry he most completely realised the vision of perfection Pavlova had planted in his soul.

She's often described as his 'muse', but it's perhaps more accurate to regard their working relationship as a partnership of equals: two great artists whose creative synergy enabled something genuinely sublime.

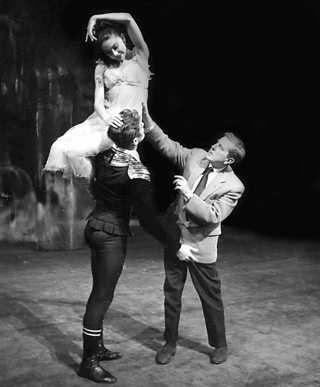

In Marguerite and Armand, made in 1963 for the classic partnership of Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, Ashton's choreography, with its reckless lifts, rapturous embraces and melting surrender transforms the romantic melodrama of the story, and Liszt's music, into an intoxicating, heroic passion that is almost overwhelming.

During his lifetime, Ashton never allowed another ballerina to dance the part of Marguerite.

Ashton created some of 20th century ballet's most glorious ballerina roles: Two Pigeons and A Month in the Country for Lynn Seymour; La Fille Mal Gardée for Nadia Nerina and a veritable roll call of roles for Fonteyn.

But his muse was always Anna Pavlova and a mark of his devotion to her can be found in his choreographic leit motif, colloquially known as the 'Fred step'. Based on a step from a gavotte that Pavlova performed, it's a simple, lilting sequence that takes just four counts to complete: posé en arabesque, coupé, pas de bourréedessous, pas de chat.

You’ll find it somewhere in virtually every Ashton ballet, often assigned to a minor character or slipped discreetly into a dance for the corps de ballet. Some see it as Fred's lucky charm, or as a cryptic puzzle, akin to the mouse that's always concealed in one of Terrence Cuneo's paintings.

To me, it's a profound expression of continuity – a subtle gesture that links dancer, choreographer and audience back to Ashton's moment of epiphany in Lima.

- Deborah Bull became Creative Director of the Royal Opera House when she left the Royal Ballet in 2002.

She is now Creative Director at King's College London, as well as a writer and presenter on television and radio and the author of four books on dance.

Read her full biography - The season celebrating some of Sir Frederick Ashton's finest works is at the Royal Ballet from 18 October - 12 November 2014.

More Frederick Ashton

![]()

Ashton: A life in dance

In an exclusive BBC Arts film, friends and fellow professionals pay tribute and share insights into Sir Frederick Ashton and his work.

![]()

Rising star performs the 'Fred Step'

Francesca Hayward, a rising star in the ballet world, gives an exclusive performance of the signature 'Fred Step' - revealed in glorious slow motion.

![]()

Ashton: Four of the best

Archive tasters of the four featured works in The Royal Ballet's Ashton season: Symphonic Variations, Scènes de ballet, A Month in the Country and Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan.