Scientists investigate what's under Antarctica's ice

- Published

More is known about the surface of some planets in our solar system than what lies beneath Antarctica's ice.

But a new map of Antarctica has revealed a detailed landscape, that's never been seen before.

Researchers have found evidence of thousands of hills and mountain ranges that have remained undiscovered until now.

They hope the new findings will help them understand what will happen if the ice melts due to climate change.

More on Antarctica

Antarctica: How has it changed

- Published6 February 2023

Scientists dig up 'world's oldest ice' in Antarctica

- Published14 January 2025

How Antarctica hides huge mountains under the ice

- Published6 June 2025

Scientists hope the new findings will help them understand what will happen if the ice melts due to climate change.

Researchers used data from satellites, and knowledge of how Antarctica's glaciers move, to work out what's happening beneath the ice.

They believe it's the most complete, detailed map ever made.

Until now, scientists have had to use measurements from the ground or air, and use radar to map under the ice but this technique left gaps.

Dr Helen Ockenden from the University of Grenoble-Alpes told BBC News: "It's like before you had a grainy pixel film camera, and now you've got a properly zoomed-in digital image of what's really going on."

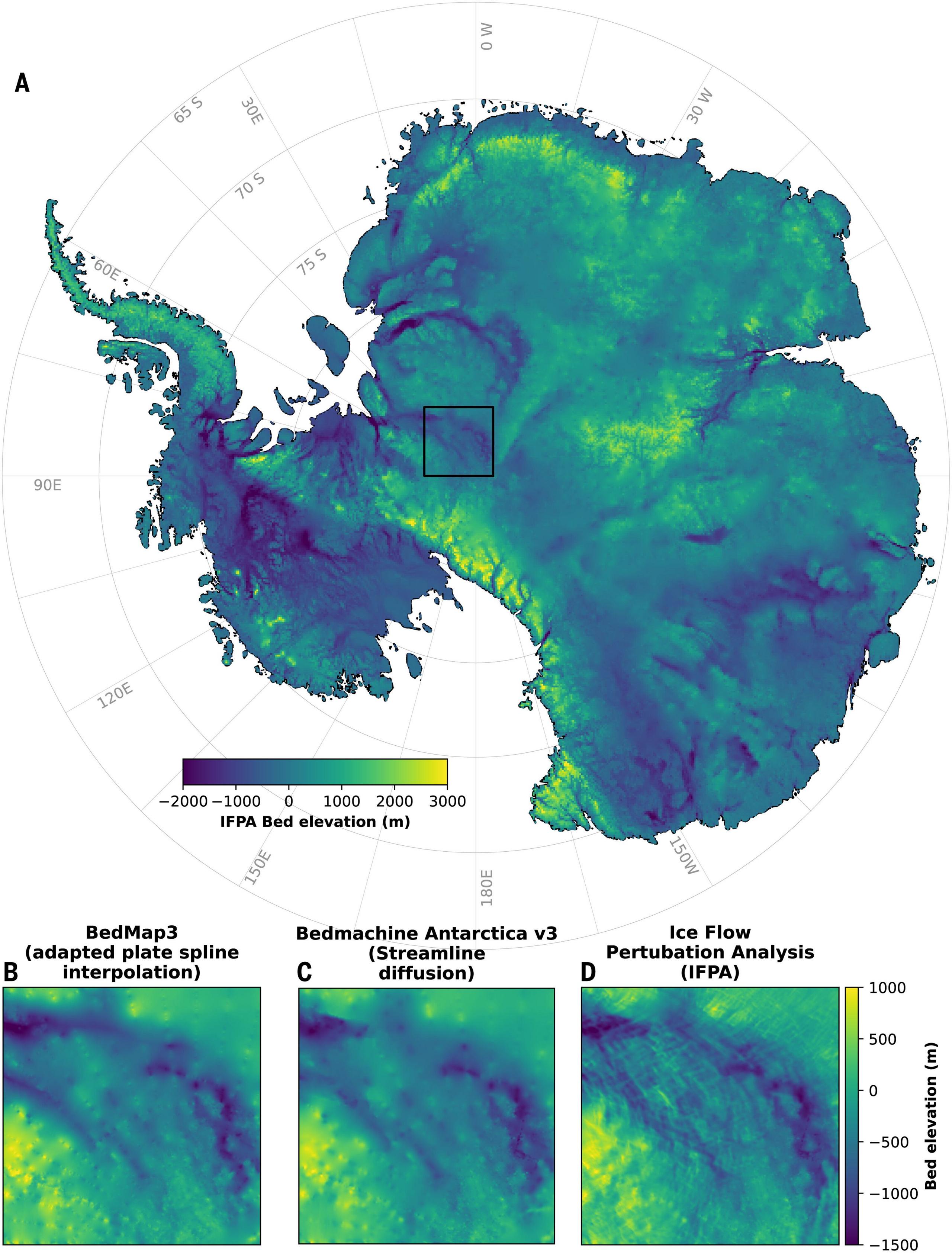

The boxes at the bottom show the difference in the detail of the maps. The image furthest to the left is the old way of mapping under the ice whereas the more detailed image on the right was captured with the new technique

The new technique has shown more hills and ridges and more details around some of the mountains and canyons that we know are already under the ice.

They discovered a deep channel that cuts into Antarctica's bed that runs the same distance as London to Newcastle (around 250 miles).

It is 50 metres deep and nearly 4 miles wide.

While the discovery is exciting, there are uncertainties around its accuracy because it relies on assumptions about exactly how ice flows.

But researchers say it's a good step forward for our understanding of the continent.