A Sikh, two Muslims, a Jew, a Christian and a Buddhist walk into a room.

The six men aren’t setting up a punchline, but holding a community meeting here on No 5 Road in Richmond, British Columbia.

Balwant Sanghera has been planning the float for the annual Canada Day parade, and reminds everyone that they can participate. Azeem Moledina wants to talk about weekend parking. Abba Brodt would like to make the street more pedestrian-friendly. Frank Klassen is new to the area and is meeting many for the first time.

All in all, it’s a pretty typical neighbourhood association meeting, filled with cups of tea and small talk.

But No 5 Road is not a typical neighbourhood - the street and the surrounding area is home to about 20 places of worship: Buddhist and Hindu temples, a Sunni and a Shia Mosque, and several churches, preaching in English, Mandarin, Minnanese, Cantonese, Arabic, Hindi, and Punjabi.

Sanghera, a member of the Gurdwara Nanak Niwas, or Sikh temple, likes to call it the Highway to Heaven.

“I do not think there is any [other] place like this,” he says.

Inside

“Whenever we worship I am reminded of the way my ancestors worshipped,” says Jonathan Wang, while sipping tea in the library of Ling Yen Mountain Temple.

In another room, nuns in putty-coloured robes are chanting softly, while worshippers quietly go in and out of the temple’s elaborate courtyard.

Built in 1996, the temple is by far one of the most impressive buildings on the highway, with lush gardens, colourful murals and ornate gilded eaves.

A small pear tree flourishes on its expansive grounds, a nod to the land’s agricultural past.

Faith did not strike Mr Wang all at once; for him, it was more of a slow awakening.

For years, he dropped his wife off on No. 5 Road without going inside the temple himself. But as he grew older, he says, he started thinking more about what might be waiting for him after death.

He longed to connect with his family back in Taiwan, and he came to cherish Buddhist teachings of reincarnation.

“I came to see it not just as a Buddhist temple but as a community where people come to get in touch with their culture.”

At the meeting, Frank Klassen is notably quiet. He’s been a pastor at Trinity Pacific Church for almost a year, but it’s his first-time meeting many of the men around the table, and he has some trepidation.

Can they shake hands in their religion? Is it rude to drink tea if others are fasting? Who is vegetarian and who isn’t?

“There’s kind of a cautious getting to know each other that takes time,” he says.

Located directly across from Ling Yen Mountain Temple, Trinity Pacific is part of the Church of God (Anderson) movement, which emphasises personal faith and one’s relationship with God over liturgical practice.

The importance of this relationship to his church and his faith can make Rev Klassen feel a bit “queasy” when people talk about the “highway to heaven”.

“Ultimately the road that leads to heaven is a narrow path, it’s not a smorgasbord,” he says.

Rev Klassen said he’s happy to participate in community events and wants to be a good neighbour but ultimately he’s more concerned with strengthening the faith of his own congregation.

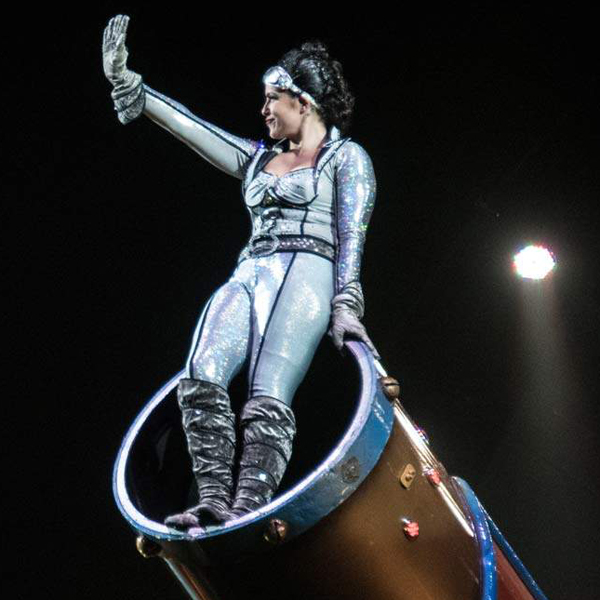

Practicing musical worship at Trinity Pacific

After leaving the meet-and-greet with his neighbours, he pulls out his Bible and turns to Matthew 7:14.

“Enter through the narrow gate," he reads.

"For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.”

When the Canadian government announced it would be dramatically increasing the number of Syrian refugees allowed into the country in 2015, it triggered an outpouring of support from across the country.

It was no different on the Highway to Heaven.

The BC Muslim Association, a Sunni mosque and cultural association located around the corner from No 5 Road, on Blundell Road, had worked with church groups both on and off the highway to sponsor refugees before.

But this was the first time they would be applying to sponsor refugees on their own. Their neighbours on the highway supported them, giving money, food and kitchen items. After raising more than C$500,000, the mosque was allowed to sponsor 47 refugees to come to Canada.

The project was especially close to the heart of Shawkat Hasan, who spearheaded the campaign.

He was just a boy when the First Arab-Israeli war broke out in the late 1940s and his family fled from the city of Ramla to a United Nations refugee camp. One day, in a bag of clothing donated by the Red Cross, he found a note pinned inside a man’s coat.

“Please write me back,” the note said in English, along with an address in Abbotsford, British Columbia.

The eight-year-old Hasan did, and thus began his long correspondence with Isaac Braun, a Mennonite from Canada who was involved with raising money to support refugees.

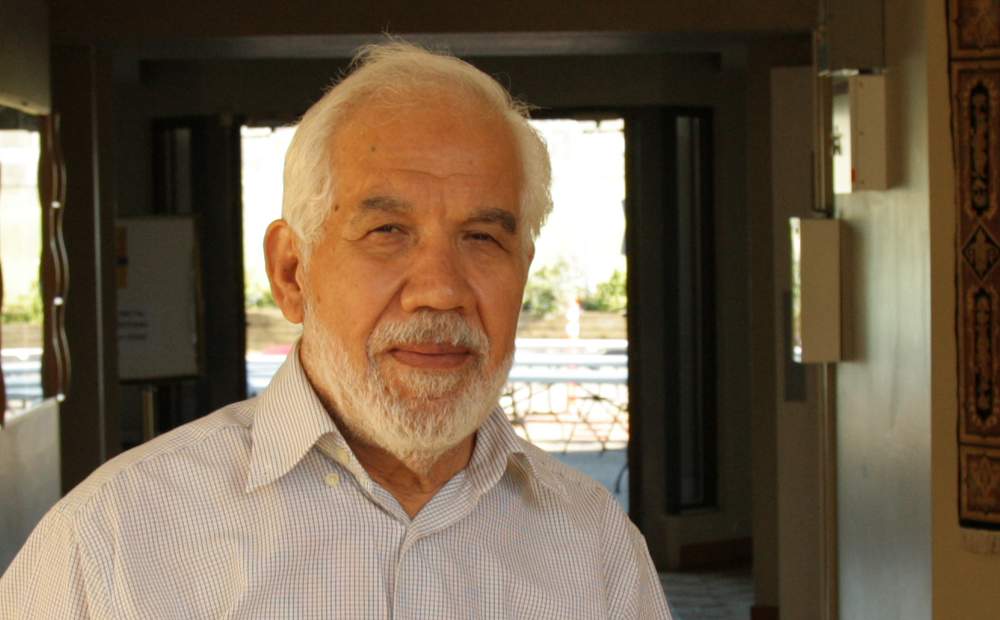

Shawkat Hasan

The two struck up a friendship that would bring them both halfway around the world.

Braun attended Hasan’s high school graduation and helped him get into a Mennonite University in the United States, which in turn set Hasan on the path to a job with the United Nations Refugee Agency in Europe.

Hasan says that it was Braun, a Mennonite, who taught him about the impact that one person can have on the lives of others.

“We are all human beings created by the same god for the same destiny,” Hasan says, while sitting outside the BC Muslim Association before evening prayers.

"People are arguing and killing each other for no reasons, except to create more misery.”

When he was finally ready to retire and his own two daughters were ready to go to university, Hasan decided to move his family to Canada, where Braun had lived.

“In Canada, as soon as you step out of the airplane you are no different than everyone else,” he says. "I love this, and I think this is an example for the rest of the world.”