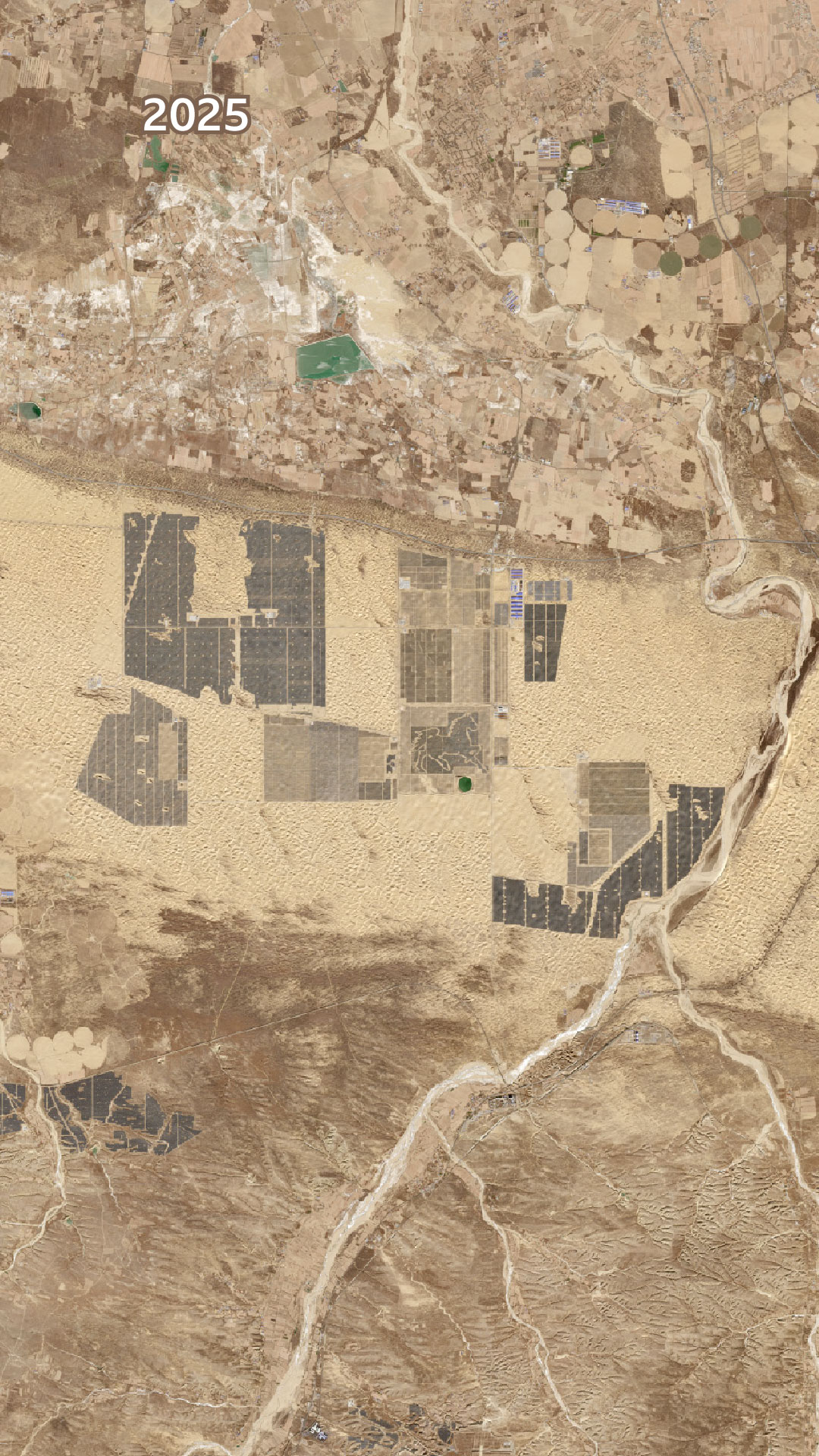

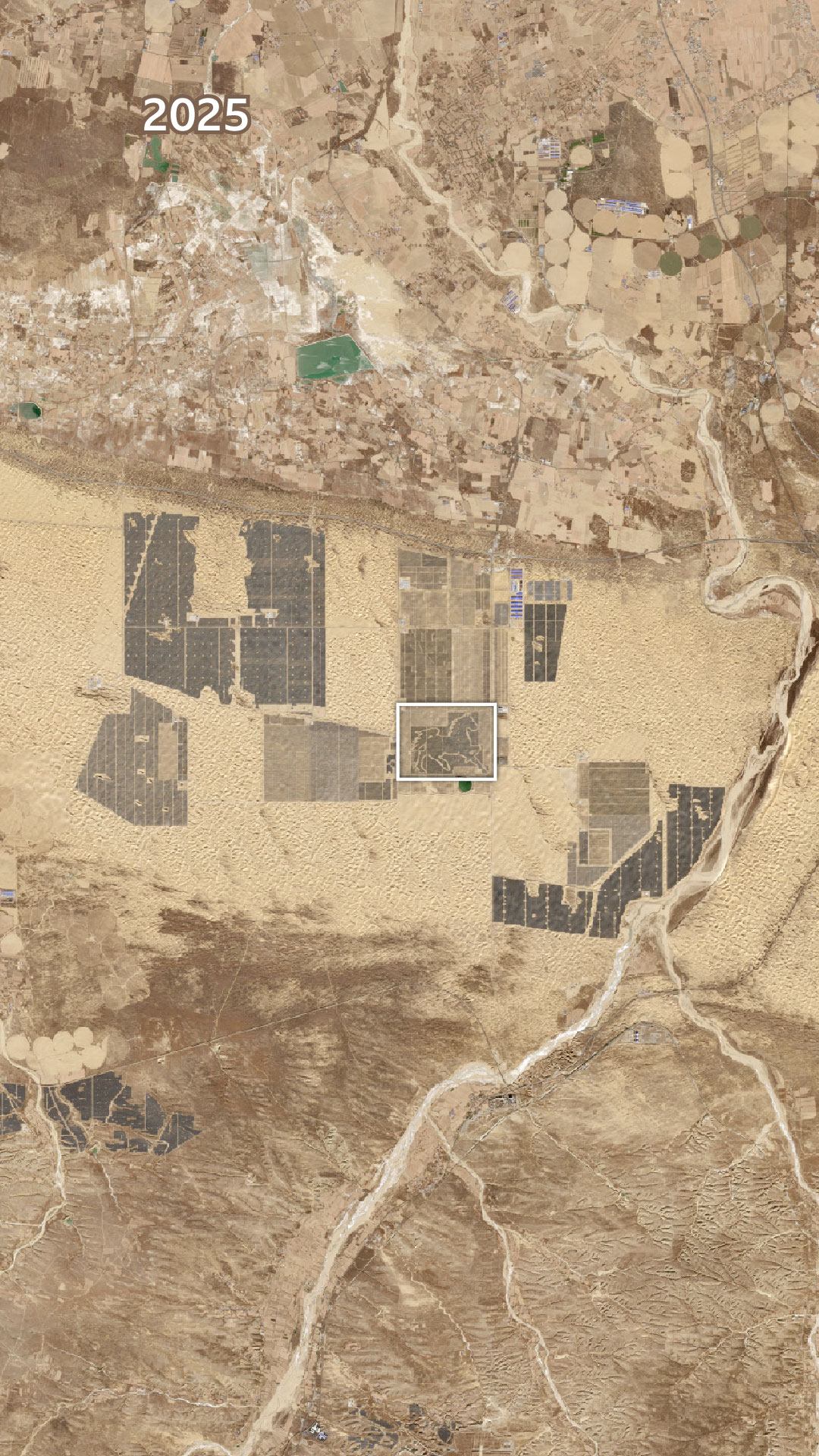

China has created a desert that no longer just reflects the Sun. It captures it.

Aluminium soaks up the rays on the golden dunes of Inner Mongolia, transforming one of the harshest landscapes into one of the world's largest solar farms.

Xin Guiyi, who has lived here all his life, seems to welcome the change.

"It used to be so dry and the desert was getting bigger," he explains, as he mixes feed for his small flock of sheep after bringing them in from the cold.

For decades, Xin and thousands of other helpless farmers in these parts watched their grazing lands shrink.

Vegetation thinned, topsoil blew away and the land lost its life because of overgrazing and rising temperatures.

The solar panels, scientists find, act as shade and windbreaks to protect the grass and restore the land. It doesn't stop the desert but there is modest impact - and that gives Xin hope.

"Wind and solar energy are abundant in Inner Mongolia. We can contribute to our country."

That sentiment may not be shared everywhere but Beijing's determination to turn China into a renewables superpower is now evident across its vast landscapes.

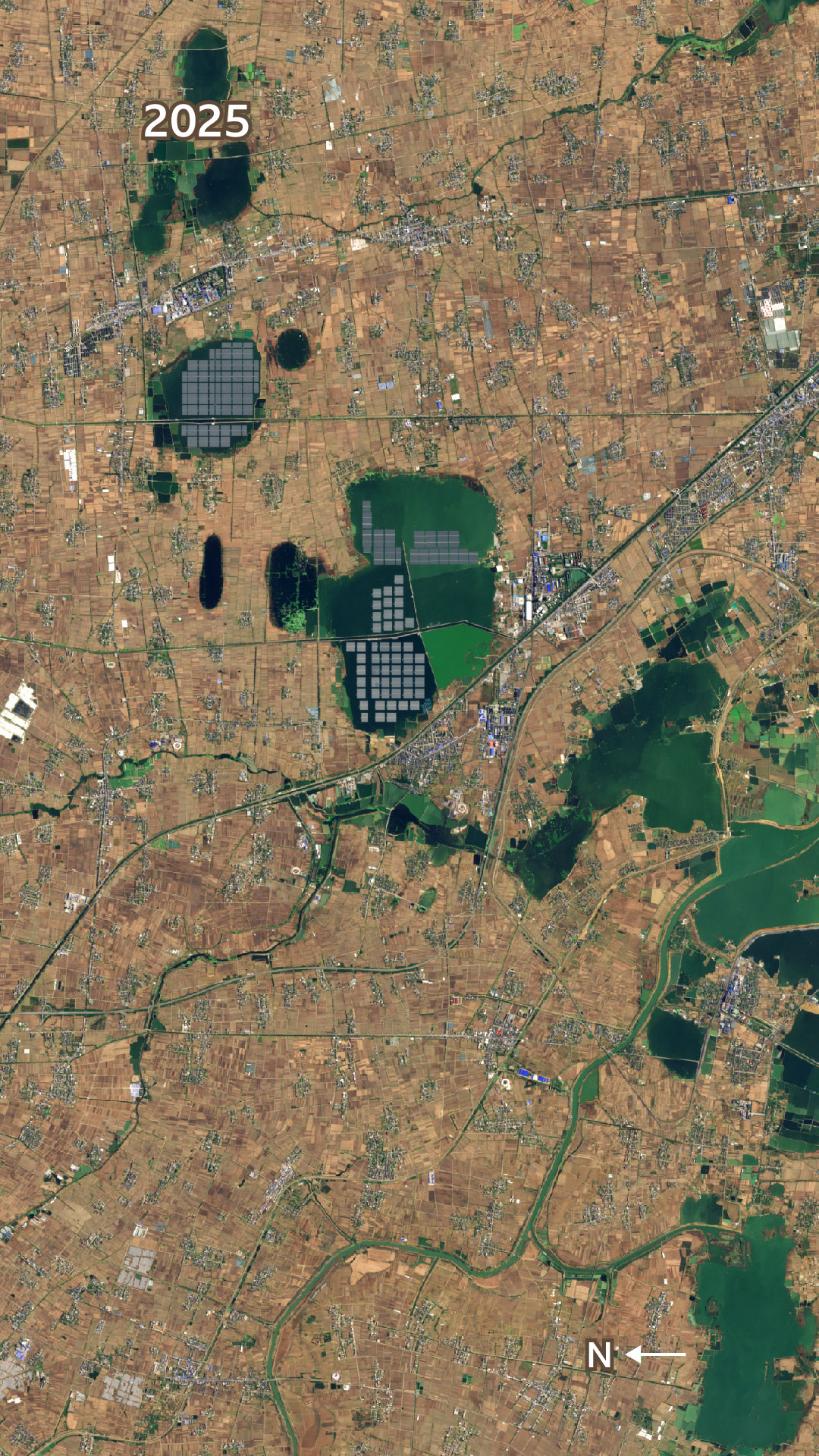

In Gansu and Xinjiang, rolling hills and open plains have morphed into massive wind and solar bases. Shimmering silicon panels sit underneath turbines, capable of generating enough electricity to power tens of millions of homes.

China, which is still the world's top carbon emitter, has been building an unrivalled green energy grid.

The country's leader Xi Jinping told the UN in 2020 that China would aim to hit peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. This goal now appears to be within reach with analysts from Carbon Brief saying its CO2 emissions have been flat or falling for 21 months.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump's White House has been pedalling back American commitment to green energy - last week it reversed a key scientific ruling that supports all federal action to curb emissions.

So Beijing finds itself in an unexpected position: at the helm of a renewables revolution.

This has been driven by both Beijing's ambition as well as the competition that it unleashed.

So much so that there has been an oversupply: of panels, key components and solar power. This has sparked price wars and a sharp decline in electricity rates, which has battered Chinese firms in the renewables supply chain.

The speed of the transition has raised concerns that opposition from locals and environmental questions have been swept aside, while communities that powered its coal industry are being left behind.

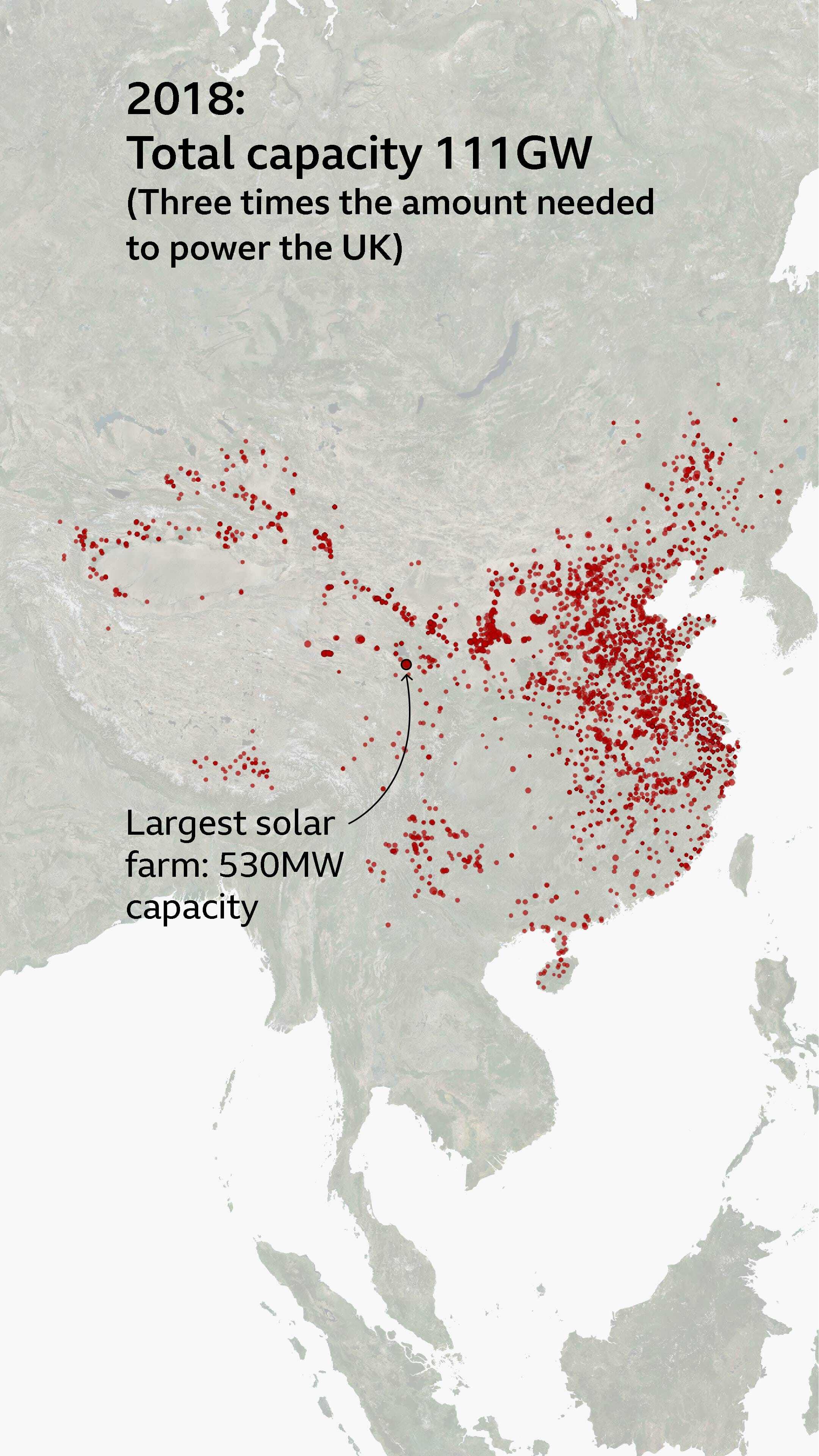

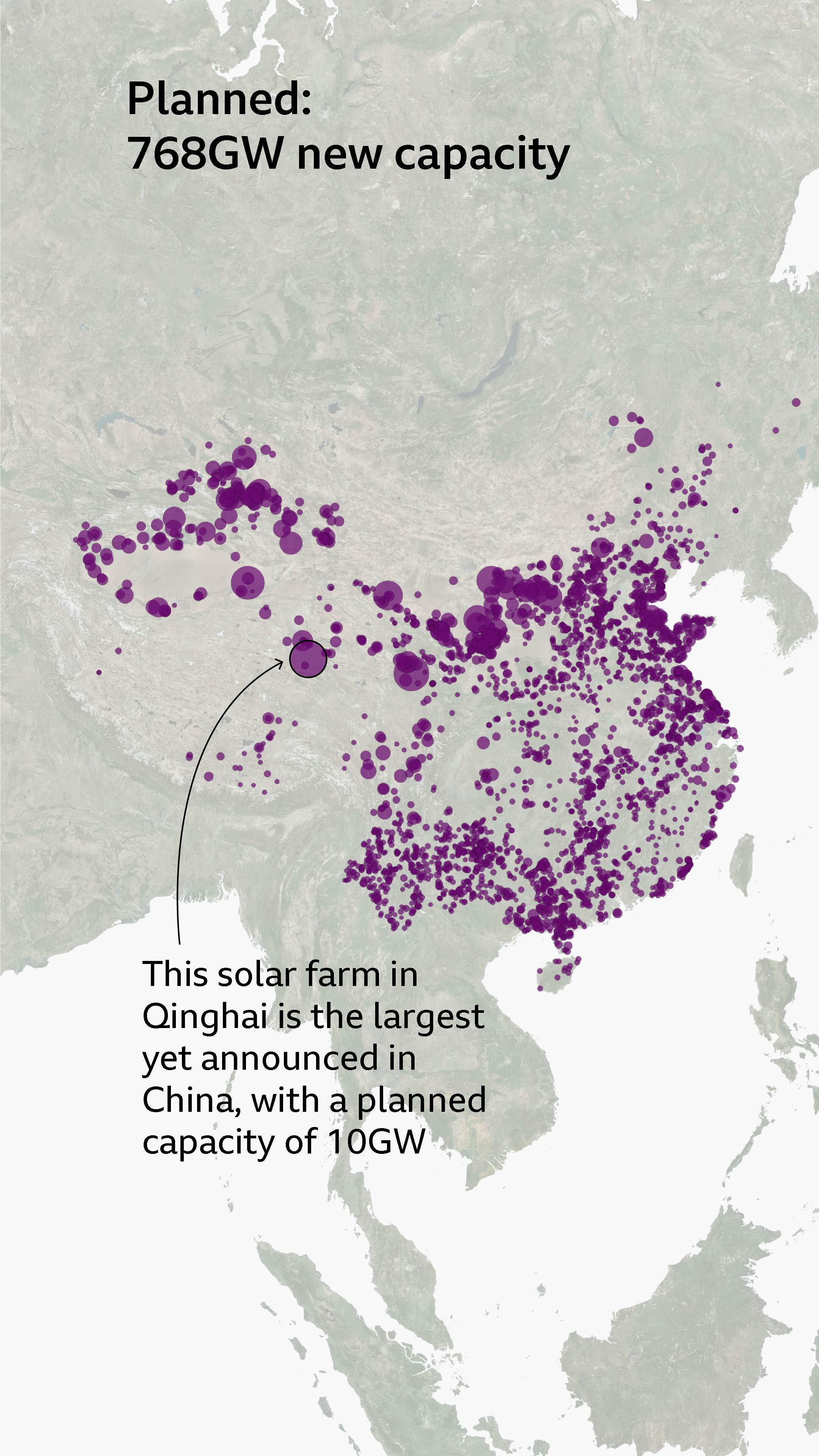

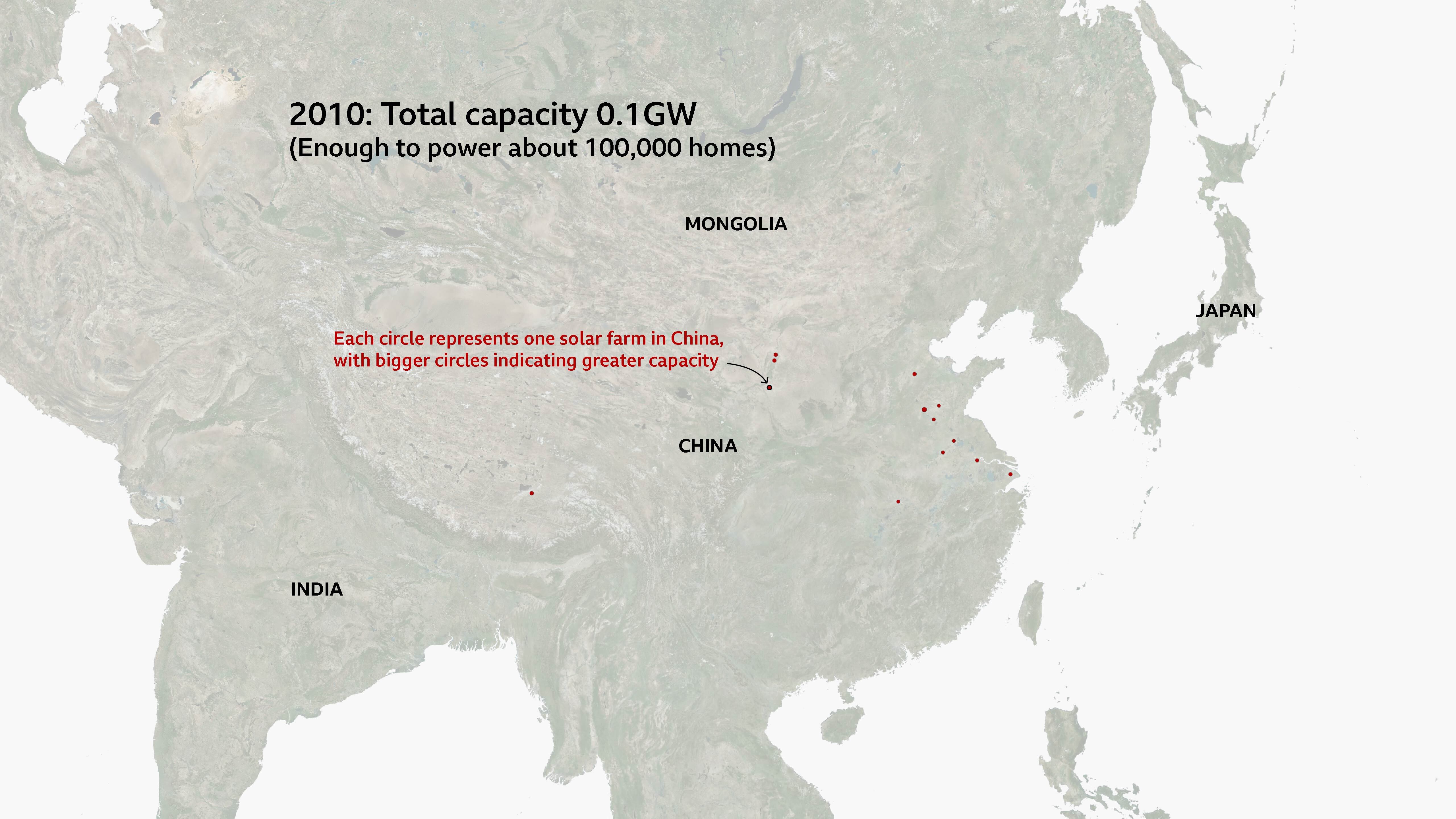

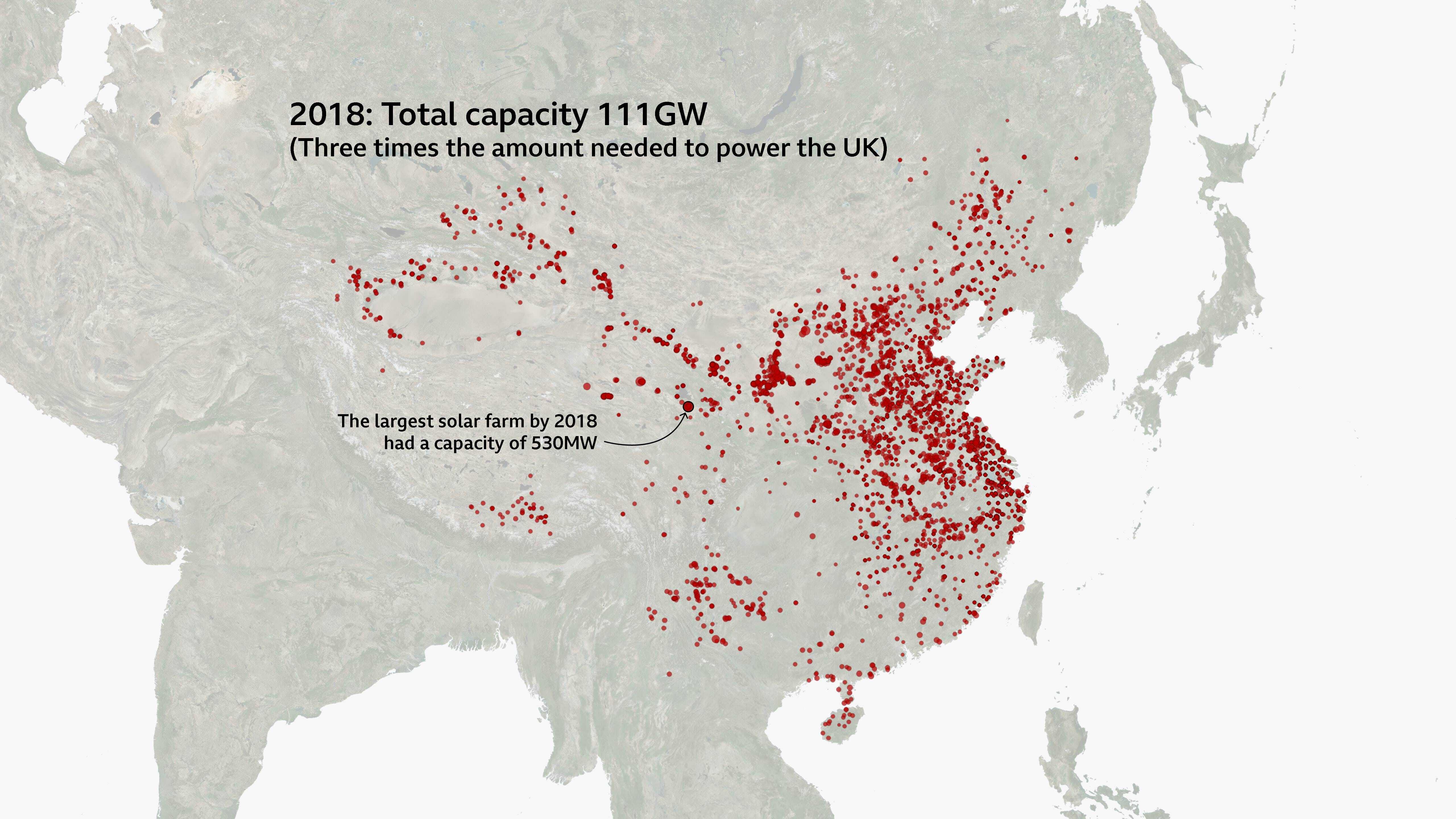

It has been an extraordinary expansion.

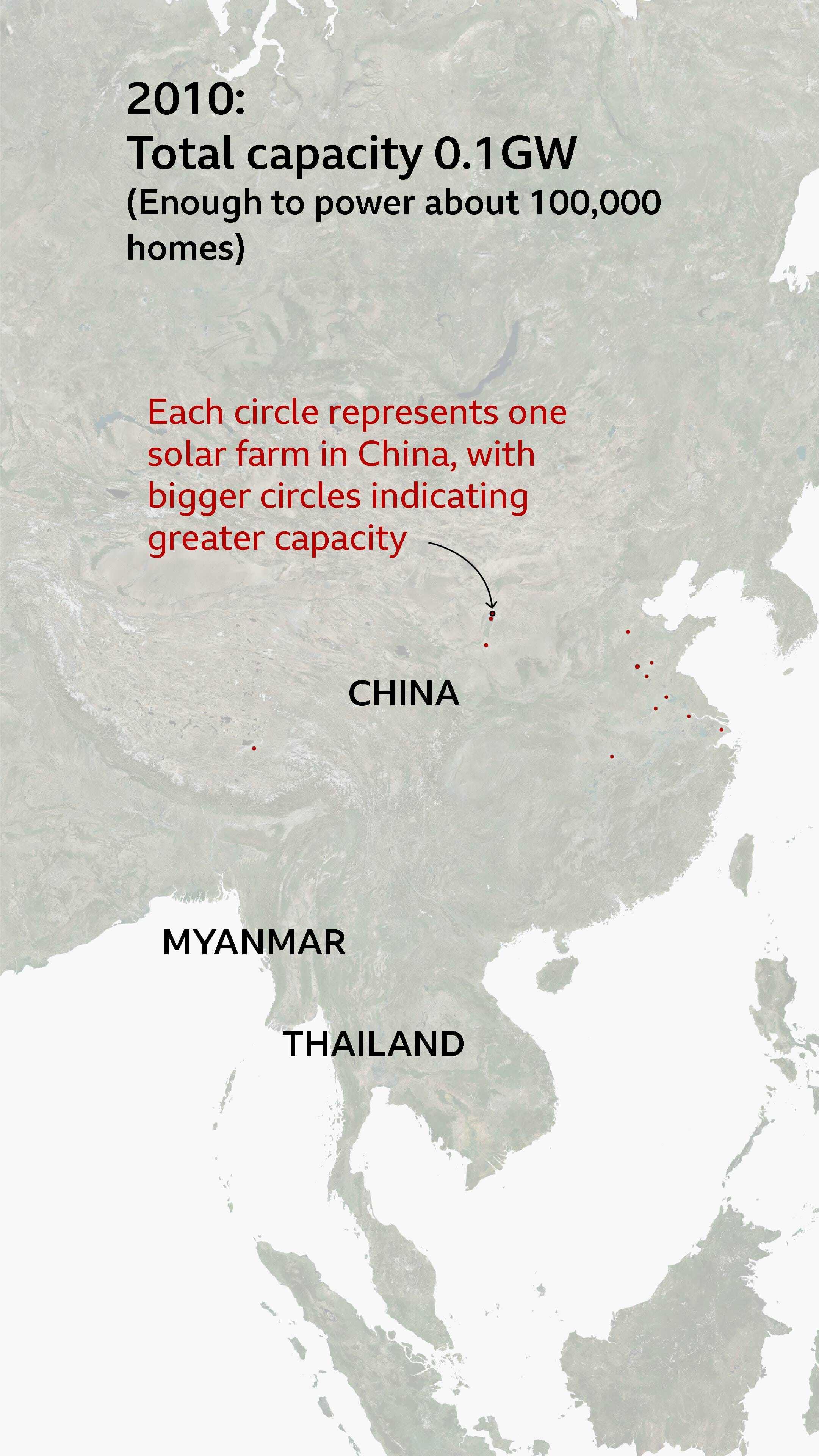

Back in 2010, China was generating less electricity from the Sun than six other countries - Germany, Spain, the US, Japan, Italy and South Korea.

Global Energy Monitor, which collected the data, says once smaller solar projects - such as panels on top of homes - are taken into account, China's total solar capacity is in fact already 1,063GW.

China's Communist Party has done this before, kicking off a massive economic transformation when it opened up the country for trade in the 1980s. The result changed the world.

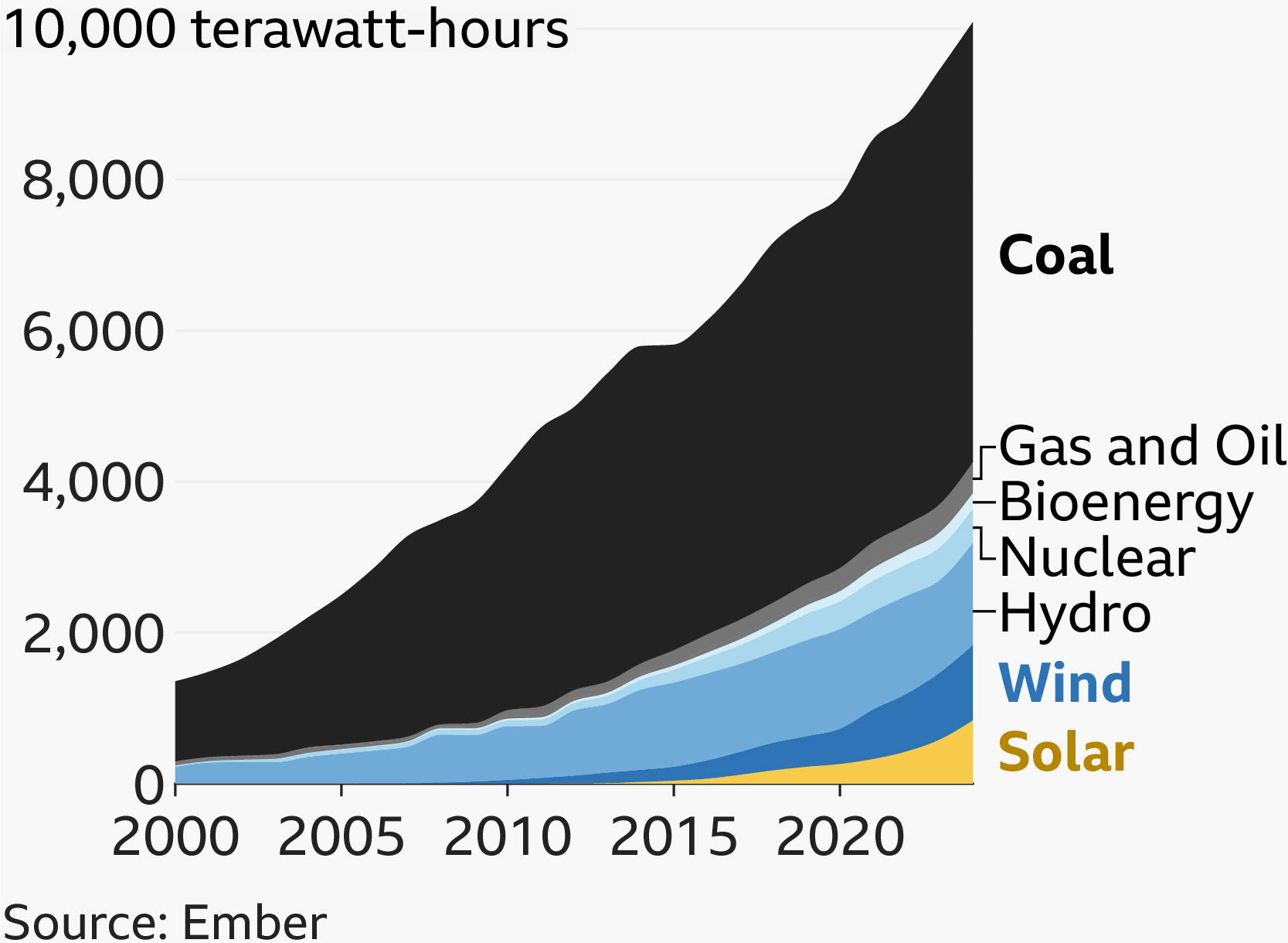

As a land of farmers turned into a formidable manufacturing and industrial power, it needed energy - and lots of it.

Coal was cheap and plentiful, and soon the world's factory became a fossil fuel-burning polluter - China overtook the US as the biggest producer of carbon dioxide in 2006.

Now China is transforming again, after directing billions in state subsidies and loans at becoming a renewables superpower.

Bejing has focused on three key industries: electric vehicles, batteries and solar panels.

Already, China makes more solar panels than the rest of the world combined.

In Xinjiang, which is a key part of this supply chain, rights groups and the United Nations have alleged forced labour and grave human rights violations, all of which Beijing denies.

And yet cheap Chinese-made solar panels are now everywhere, from rooftops in Pakistan to Jamaica, revealing just how indispensable China has become to the world's green energy goals.

This has frustrated the West, especially the EU, which has long accused China of resorting to "unfair trade practices" by manufacturing too much and pricing out competitors.

But today, one out of every seven solar panels produced worldwide is made by a single Chinese facility, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Oversupply has also become a domestic challenge.

Solar manufacturers have been cutting prices to stay competitive, while investing to keep up with the latest tech and rising raw material costs. The result: the country's top solar panel makers predicted they would lose up to 38.4 billion yuan ($5.5bn; £4bn) for 2025, Nikkei reported last month.

Six provinces reportedly cancelled 143 wind and solar projects with a combined capacity of 10.67 GW in the second half of last year.

Beijing has been stepping in to curb the glut. But waste and storage remain big challenges as China's grid, which still relies on coal and thermal power, transitions to absorbing the volume of solar and wind power that is being generated.

This transition has happened in China much faster than anywhere else.

China has added more capacity for generating solar energy than the rest of the world combined for several years.

The same is true for wind power.

Some experts argue that China is so far ahead in renewable tech that it could take other countries decades to catch up.

"It's a resounding victory for China," says Li Shou, from the Asia Society's Climate Hub. Their lead is "so significant and so systematic... it's not a question of whether other countries should work with China - it's how.

"If you are a country still debating whether to work with Beijing - then you will be increasingly left in the dust."

Even in China, there is often little choice but to go along with Beijing's plan.

In the southern province of Yunnan, the lush mountains of Funing county were once home to one of the world's largest tea growing regions.

Now the beloved tea crops in Paohuo village are being replaced by one of Xi's "new economic forces": solar panels.

Large industrial drones buzz overhead, deploying panels into position. All over the hillside, workers are busy reading installation guides or hammering the metal into soil.

Watching the scene is Duan Tiansong, a tea farmer. "My heart aches. I cannot sleep at night thinking about this."

He holds up leaves shed by the few tea plants that remain among the solar panels.

"Look at this land. It was a great green tea farm, and now it's like this," he says.

He worries that uprooting so many tea plants to install panels has loosened the soil, raising the risk of erosion: "In other places where they cut trees, they've already caused landslides."

Anxious about the dangers, the 35-year-old has pleaded his case to local officials but he says he has received no reply. "I do not understand why my local government wants to introduce this."

Duan waves a contract, which says the village agreed the land could be rented for other purposes. They were not told it was for a solar farm, he says.

Thirty-three villagers have signed it but few of them use the land to grow tea, Duan says.

He has not signed it.

Work progressed anyway and we saw the China Energy Engineering Company installing solar panels.

We asked the company whether the villagers were consulted before they began work, and for evidence that the land was obtained legally. But we received no response.

It's hard to see Duan's resistance slowing down the activity all around us.

The hill is already covered in poles or panels. And this is only one of about 300 solar installations across Yunnan that began in 2025 alone.

China is in a hurry.

When that happens, few things can stand in the way of the Communist Party's ambition. In the late 1990s it relocated more than a million people, by some estimates, to build the world's largest dam on the Yangtze river despite opposition and environmental concerns.

In today's China, it is even harder to measure the number of protests against these projects.

Searches on Douyin - China's TikTok - yield videos of villagers protesting against solar projects, on their rooftop or on their land, but they are quickly stifled and then censored online. They are usually opposed to losing their farmland, or unhappy with the compensation offered.

Companies that want to create large solar panel installations must submit a thorough environmental report, but smaller solar parks only need to provide basic paperwork.

Scientists say that the impact of installing solar panels can be mitigated with careful planning, and by working with farmers to share the land.

Concerns do exist, about the pace of change, and its longer-term consequences. China's electric vehicle and battery makers are powered by its mining of rare earths - for which China is paying a steep environmental price, our earlier reporting found.

It is also not clear what plans Beijing has for the millions who work in the coal industry, which it wants to phase out.

But frank warnings are rare in China, especially as projects are approved by local governments eager to show they are doing their bit to support Beijing's renewables push.

That push is certainly starting to pay off.

"Clean power has grown fast enough to cover all the increase in electricity demand in China and then some," says Qi Qin, from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

"Fossil fuels are being pushed out of the mix. This is the first real sign China is approaching a structural turning point."

And yet China is running two races at the same time.

It is trying to keep the lights on for the world's second-largest economy, and its 1.4 billion people, while building renewables capacity that can replace coal.

That is one of the reasons the country is still relying on fossil fuels and building coal plants.

China is using more power every year and coal was still responsible for generating 58% of that in 2024 - although the rapid growth of wind and solar power means they were contributing 18%.

But for some, the transition to a greener China feels like yet another change they cannot keep up with.

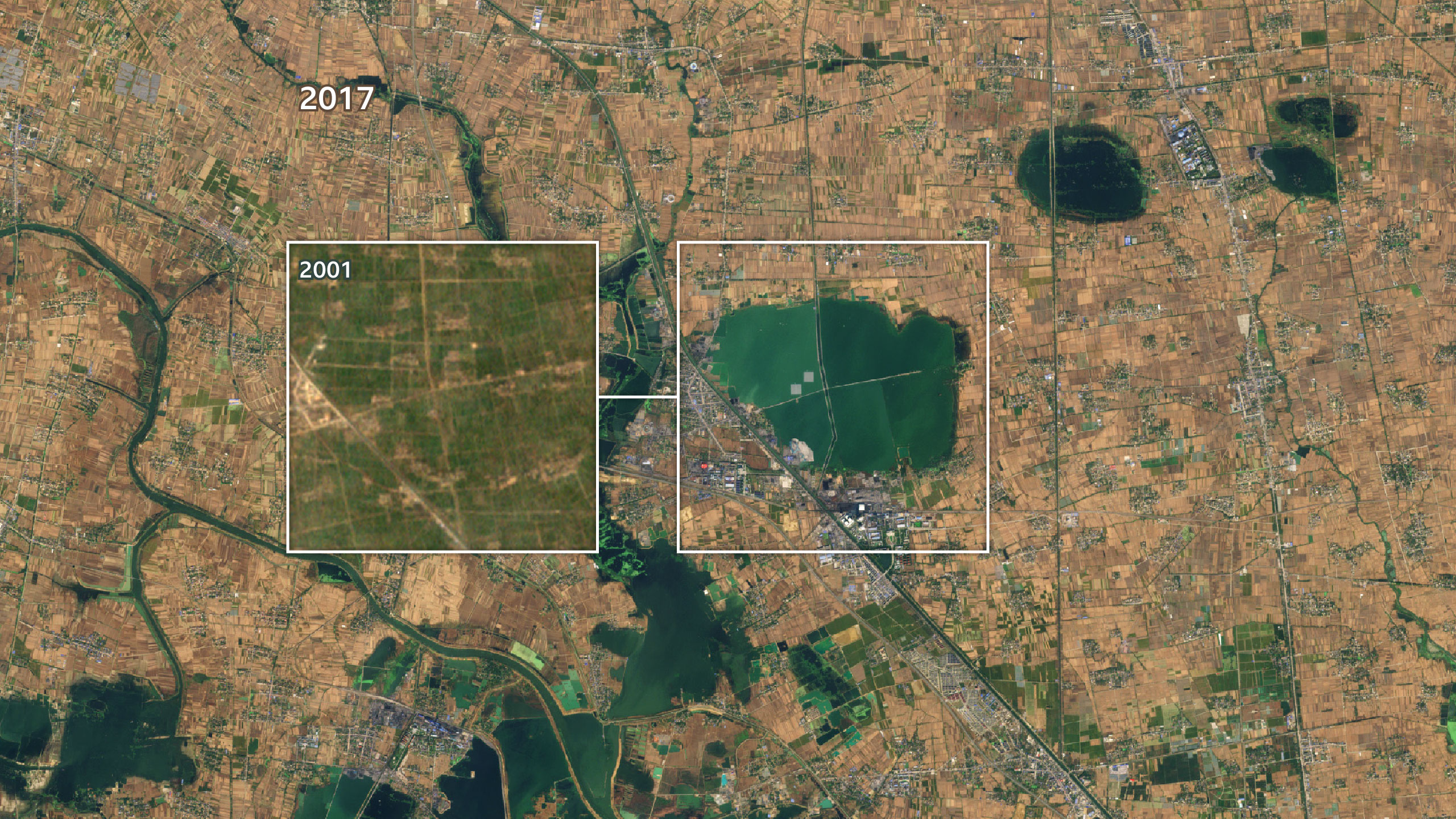

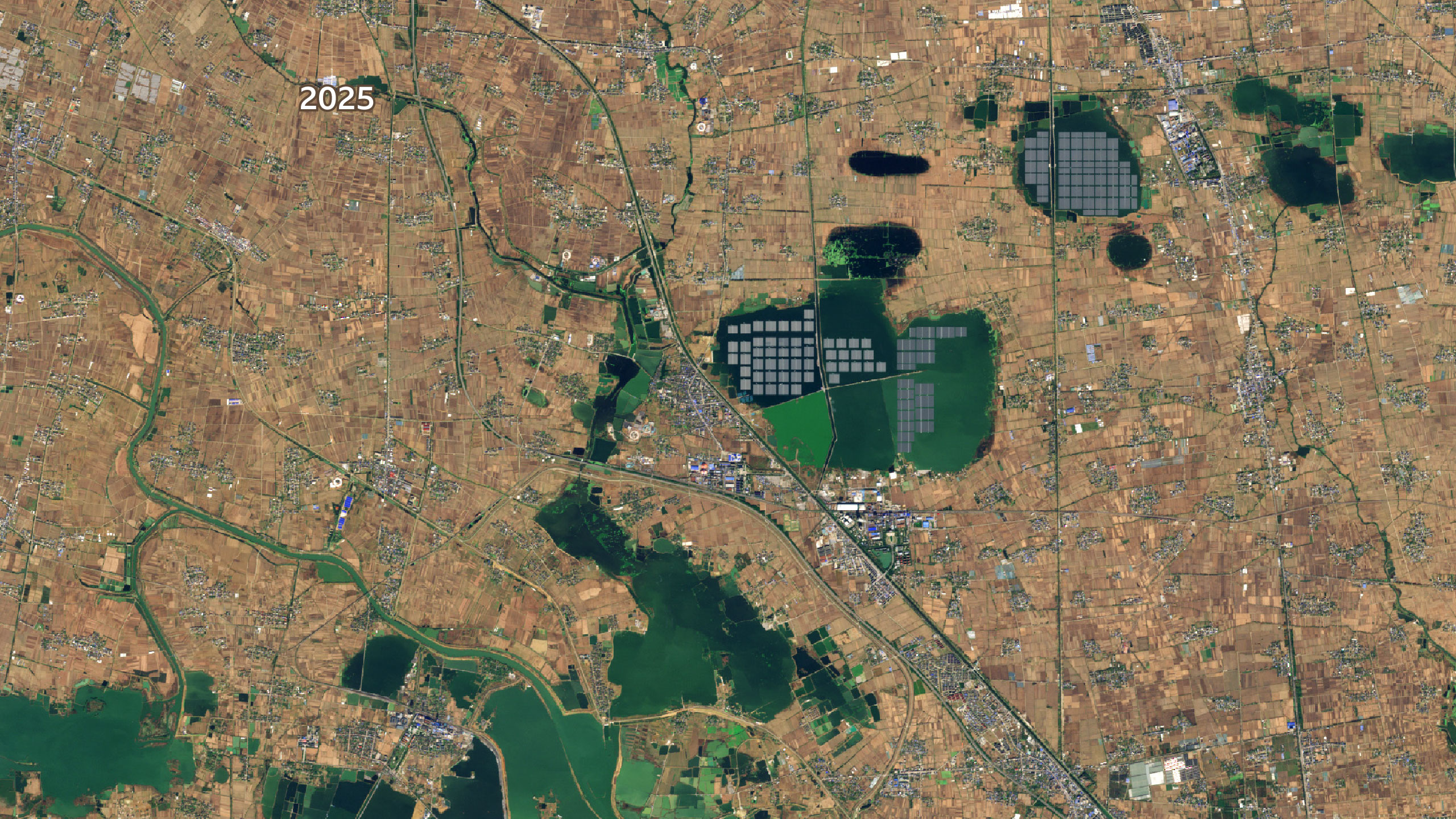

In 2007, in the central province of Anhui, the Huainan Mining Industry Company built one of the largest underground coal mines in Asia, extracting about five million tonnes of coal each year.

When the mine opened thousands of people lived and farmed the land above it - it took only a few years for villagers to start reporting cracks in their houses and the ground itself.

Mr and Mrs Guo are among the few villagers who refused to leave.

When we meet them, they are chopping wood to keep warm as a low, thick smog gathers around them, snaking out from the towers of the coal plant nearby.

They point towards their home, now submerged in water.

"It's all gone," the 73-year old says as her husband keeps working. "I didn't manage to save anything."

The couple had an option to relocate but chose to live near their old home, and farm what little land they could to survive.

A makeshift tarpaulin covers some of their belongings.

"No-one will employ us," she says. "If we stay, at least we can grow crops."

About the data

The data on solar capacity in China and the rest of the world is published by Global Energy Monitor (GEM). GEM collects information on utility-scale (1 megawatt or more) and distributed (less than 1 megawatt) solar capacity.

Total utility-scale solar capacity is the amount of power that GEM estimates could reach the electricity grid. The capacity of individual projects can be reported in direct current (DC), alternating current (AC), or not specified at all. Electricity grids use AC, so GEM converts DC and unspecified values using a method described here.

In this article we quote total capacity in AC and individual projects as they were originally reported (DC, AC or unspecified).

The operating start year for about 2,000 farms with a combined capacity of 35 gigawatts is unknown - they are included only on the 2026 map but may have opened several years earlier.

About 100 solar farms included in the data are used for generating green hydrogen. While still forming part of China's solar capacity, these projects feed electricity directly into an electrolyzer to produce hydrogen and do not contribute to the grid.