The memory hunters

If you had 60 seconds inside your home before it was set to be destroyed, what would you grab?

Jewellery perhaps, or a beloved childhood toy, but for many people there is nothing as priceless as a family photo.

After the most powerful earthquake in Japan’s history rocked its eastern coast, triggering a series of towering tsunami waves, Tomomi Shida searched the primary school she worked in, looking for her students.

Tomomi was an hour away from her home in the seaside town of Ofunato. She had no way to get there - no idea if her own family had survived. “The only way to get information was over the radio. I heard that Ofunato had been obliterated. This was the first time I understood that the place where I lived no longer existed,” she remembers. She didn’t know it at the time, but almost 16,000 people were killed in the March 2011 disaster. Many of their bodies have never been found.

It took the 48-year-old several days to locate her teenage boys and her elderly mother-in-law. And then she had to find her husband - a volunteer firefighter whose job it was to close the town’s tsunami gates. Miraculously, he was alive. “We hugged and we cried,” Tomomi remembers.

But only a footprint of their house remained and almost everything they valued was gone. Or so they thought.

Several weeks later, one precious possession re-emerged.

“Someone from the fire brigade recognised my husband’s face in a photo,” Tomomi explains. It had been sticking out of a pile of waste; a sudden reminder of ordinary times amid the endless stretch of muddy debris.

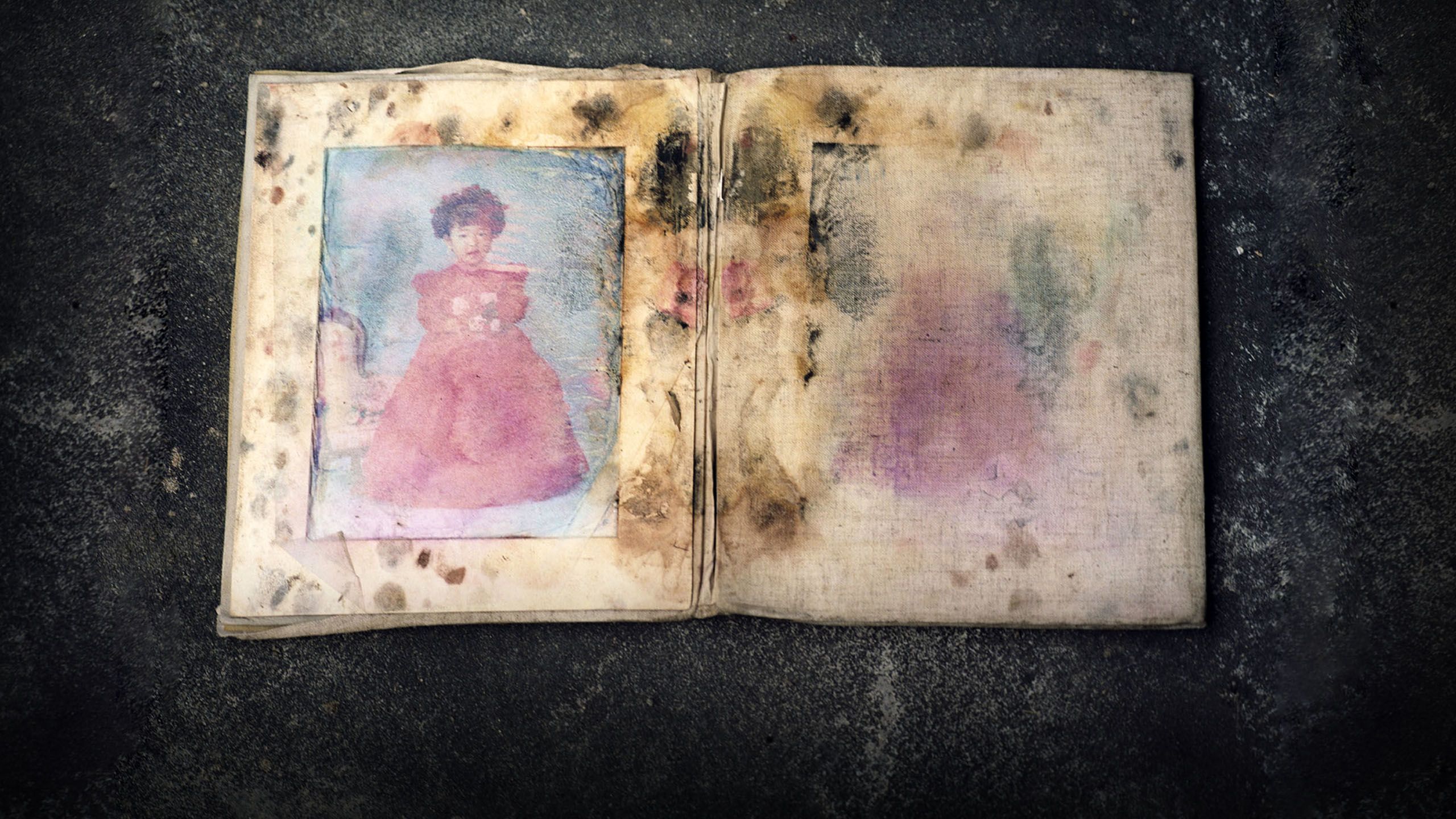

It was a simple photo studio portrait, taken when the boys were still young, posing with perfect bowl haircuts and chubby cheeks - in fact, a few copies of the same photo were found.

Those images instantly became the family’s most valuable possession - a memory of a simpler, happier time, a time that could never be photographed again.

But all of them were damaged. Tomomi’s eye was wiped off in one, her husband’s features were missing in another.

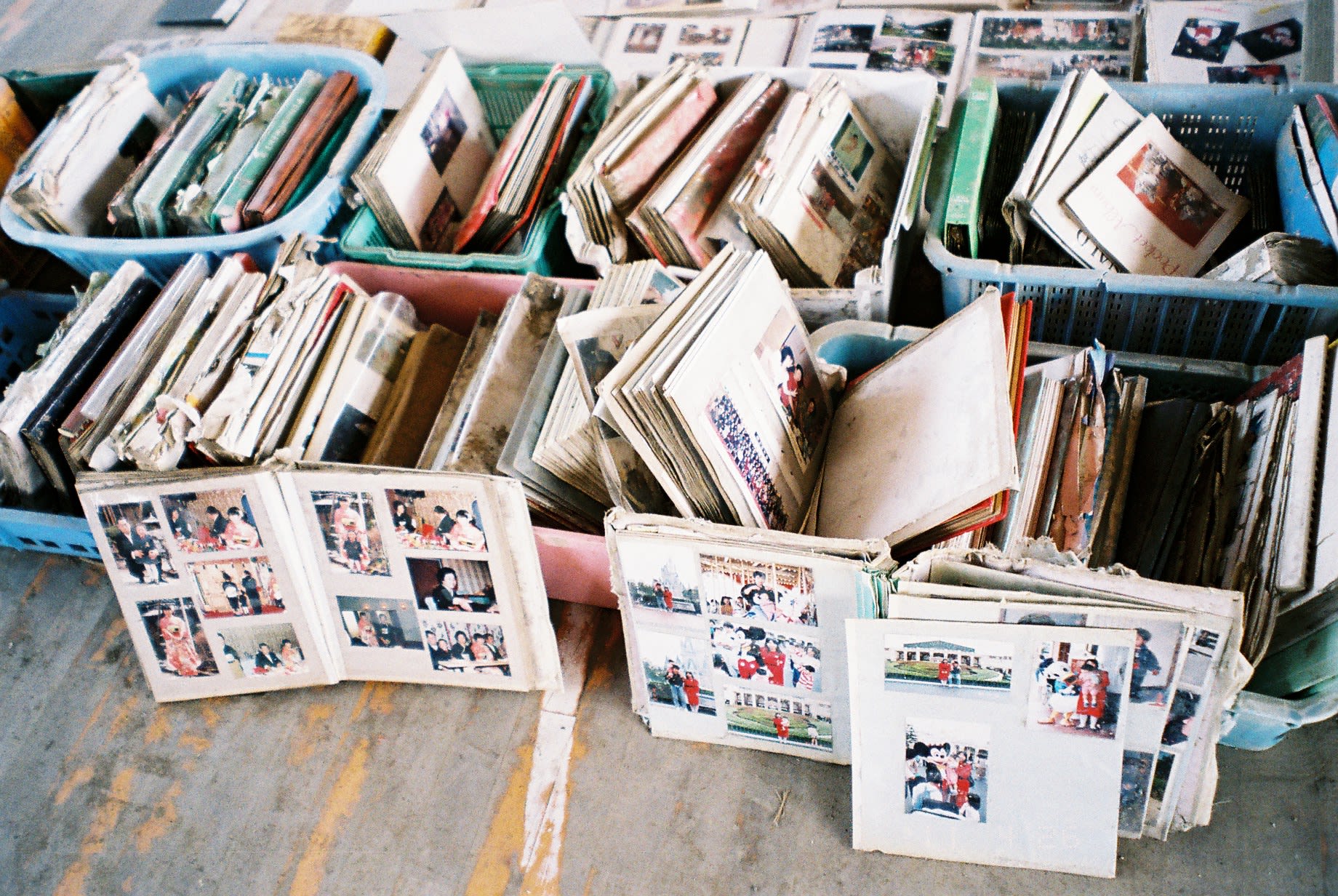

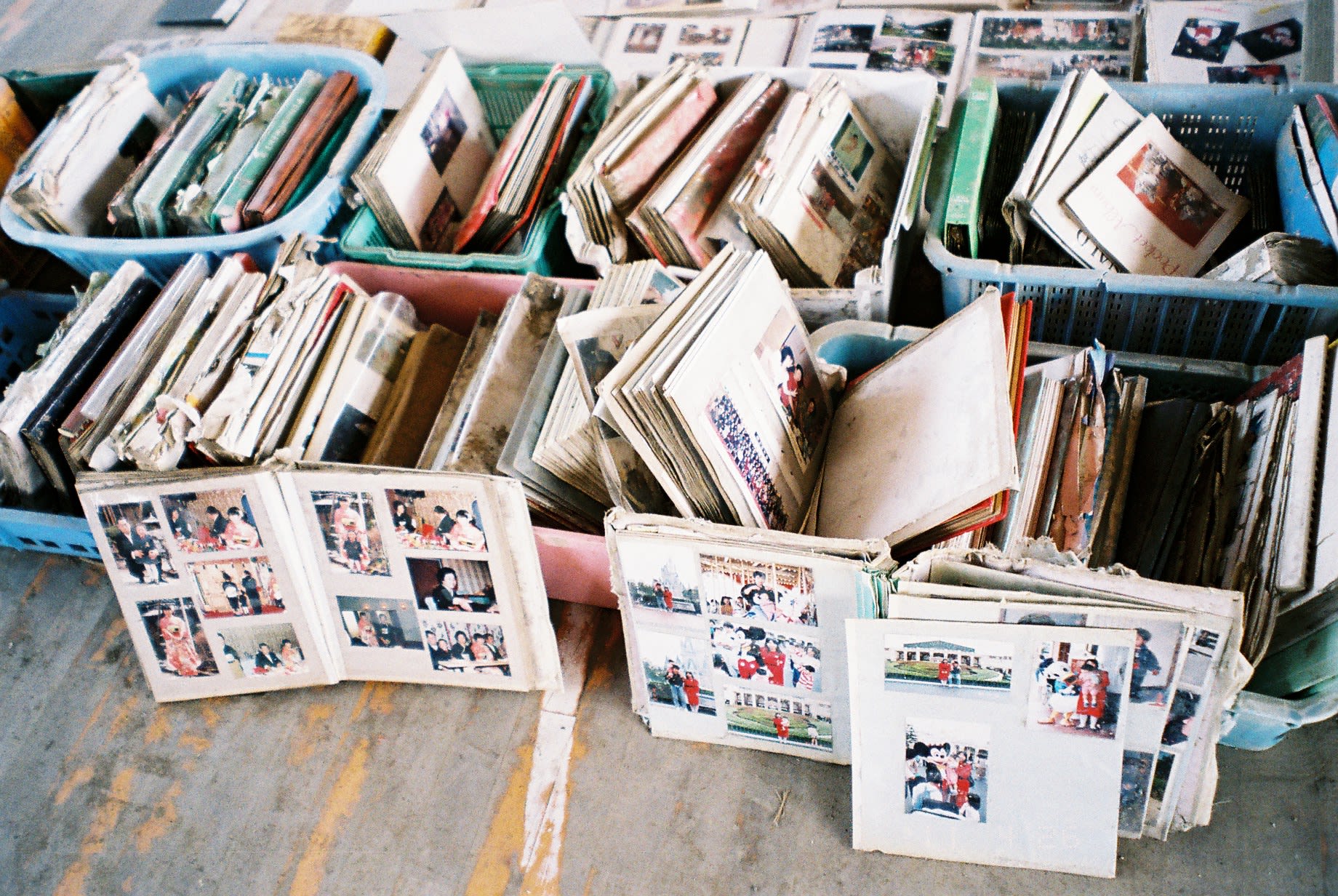

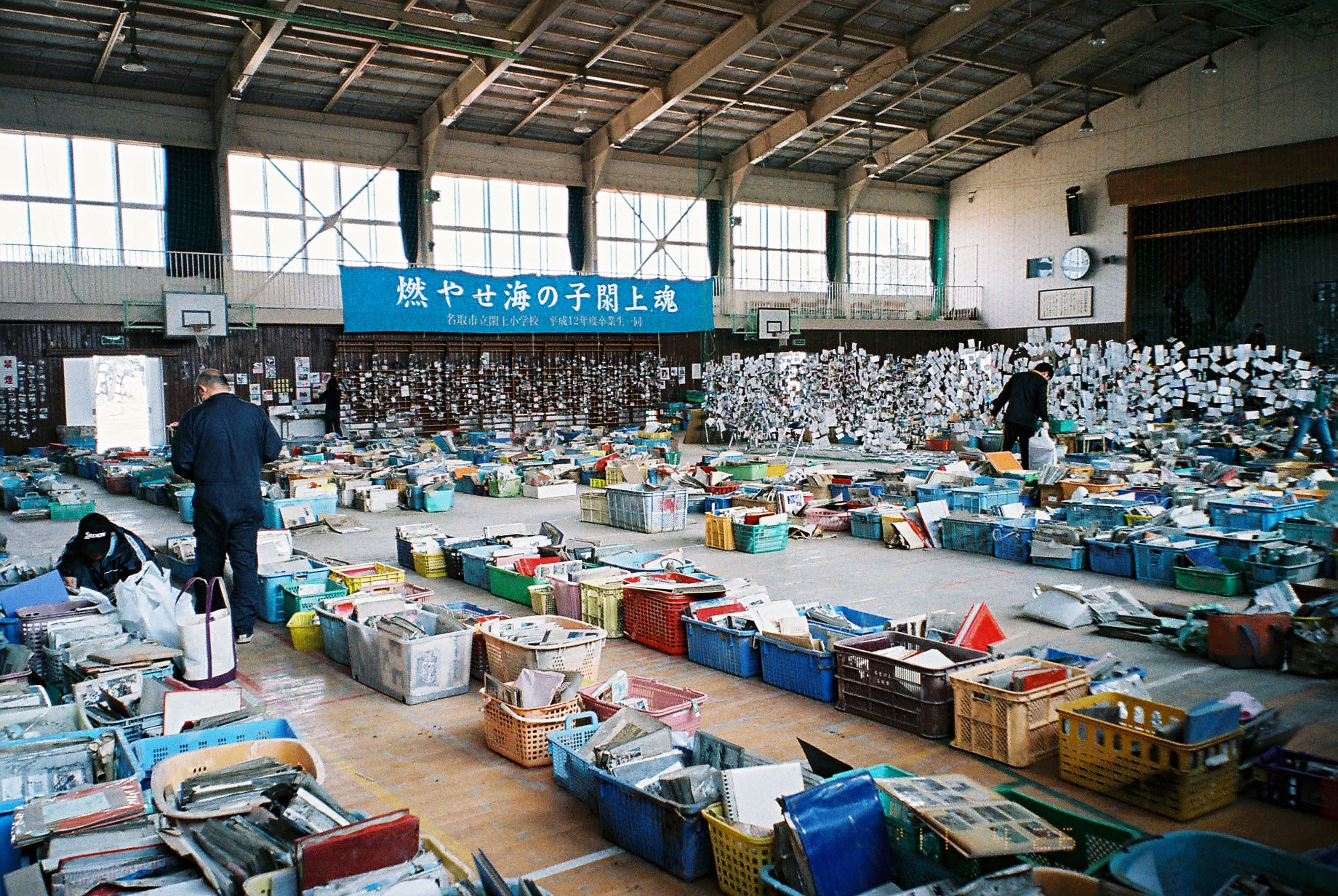

As the Shida family was realising what they had lost and found, their experience was being replicated up and down Japan’s east coast. Two weeks after the tsunami, the Japanese rescuers looking for missing people received orders to also salvage photographs. At the end of each street corner, they placed all the photo albums and framed photos they could find inside plastic crates. Most were covered in mud and had been blurred by water. They had been located but they hadn’t yet been saved.

Yuichi Itabashi, a chemical engineer by training, was watching the horrors of the tsunami zone safely from his house in Tokyo. But what he saw made him realise he could help.

“A few weeks after the tsunami, there was a television news report that showed some people in the tsunami area trying to clean their photos. I saw they were washing them roughly,” he says with a shudder.

At the time, Yuichi worked for Fujifilm, one of Japan’s oldest camera companies. He was in charge of their photo imaging division — the part of the company that had made a lot of the photographic paper he was watching survivors clean on TV.

“Someone said they were gathering the photos in every town. I thought we needed to go there. Though, to be honest, we didn’t really know how to clean photos either,” he admits. But he did know that those people were in danger of destroying the things they were trying to protect.

He worked with his colleagues to recreate tsunami conditions over a couple of days, applying seawater and mud to photos to mimic the damage. Then, they figured out how to make the photos whole again. They had to work quickly. Calls were coming in to Fujifilm from up and down the coast asking how to save photographs.

Without telling his company, Yuichi rented an electric car, fearing he wouldn’t be able to find working petrol stations. Accompanied by two colleagues, he drove into the tsunami zone. They wanted to track down the group of people they’d seen on TV, to show them how photos should be cleaned so they wouldn’t be ruined.

“We thought the survivors needed water, food and a place to sleep, but what comes second? Not money. The survivors said they needed their photos.

“Houses, cars and clothing can be bought again when we make money. But it’s impossible to buy those memories.”

The clock started ticking on those memories as soon as salt water hit family homes, drenching photo albums and portraits hanging on walls. Photos can last about 72 hours if they’re wet, but after that, the gelatine that holds the image onto the photo paper starts absorbing water. Micro-organisms start eating away at the gelatine and mould grows, making the image brown and blurry.

For decades, Japan has nurtured its love affair with photography.

“Since the 1960s, every family has had a camera,“ says photo conservationist Yoko Shiraiwa. “So every family probably had photograph albums in their houses.”

Now, of course, photographs are usually taken on digital cameras and often instantly saved into cloud storage. But there’s an enduring power to photographic prints, to photos that take up physical space. In the tsunami, Yoko says, everything that was stored on hard disk drives, memory sticks and CDs was lost.

In normal times, Yoko works for museums and private collectors, trying to extend the lives of priceless historical objects. Right after the disaster, she watched the same news reports as Yuichi which showed survivors who were cleaning muddy photographs. She too understood that there was only a small amount of time before the wet photos would disintegrate. Discarding the complicated methods she normally uses to clean photos, she also developed a simple cleaning method using water and raced to the tsunami zone to pitch in.

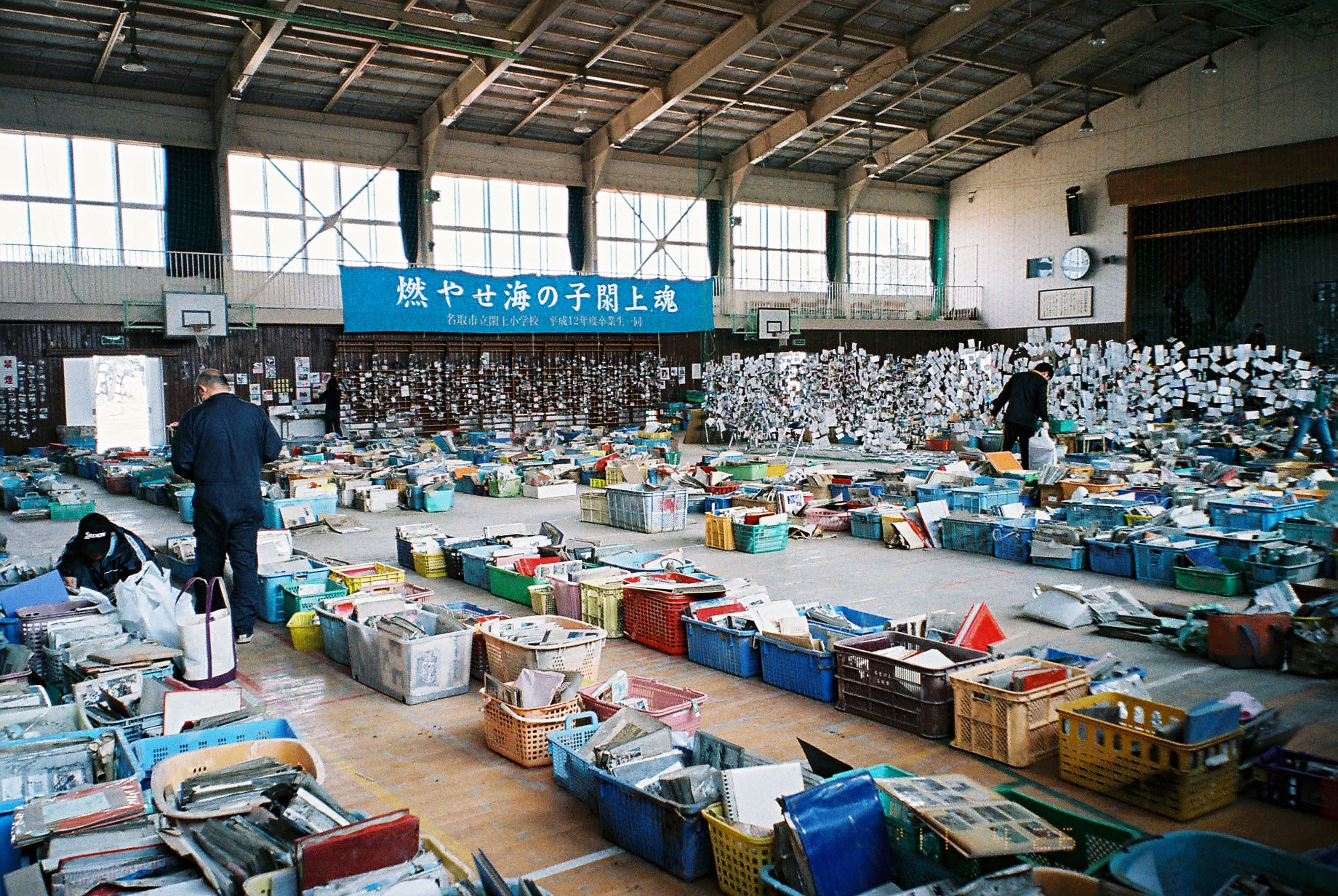

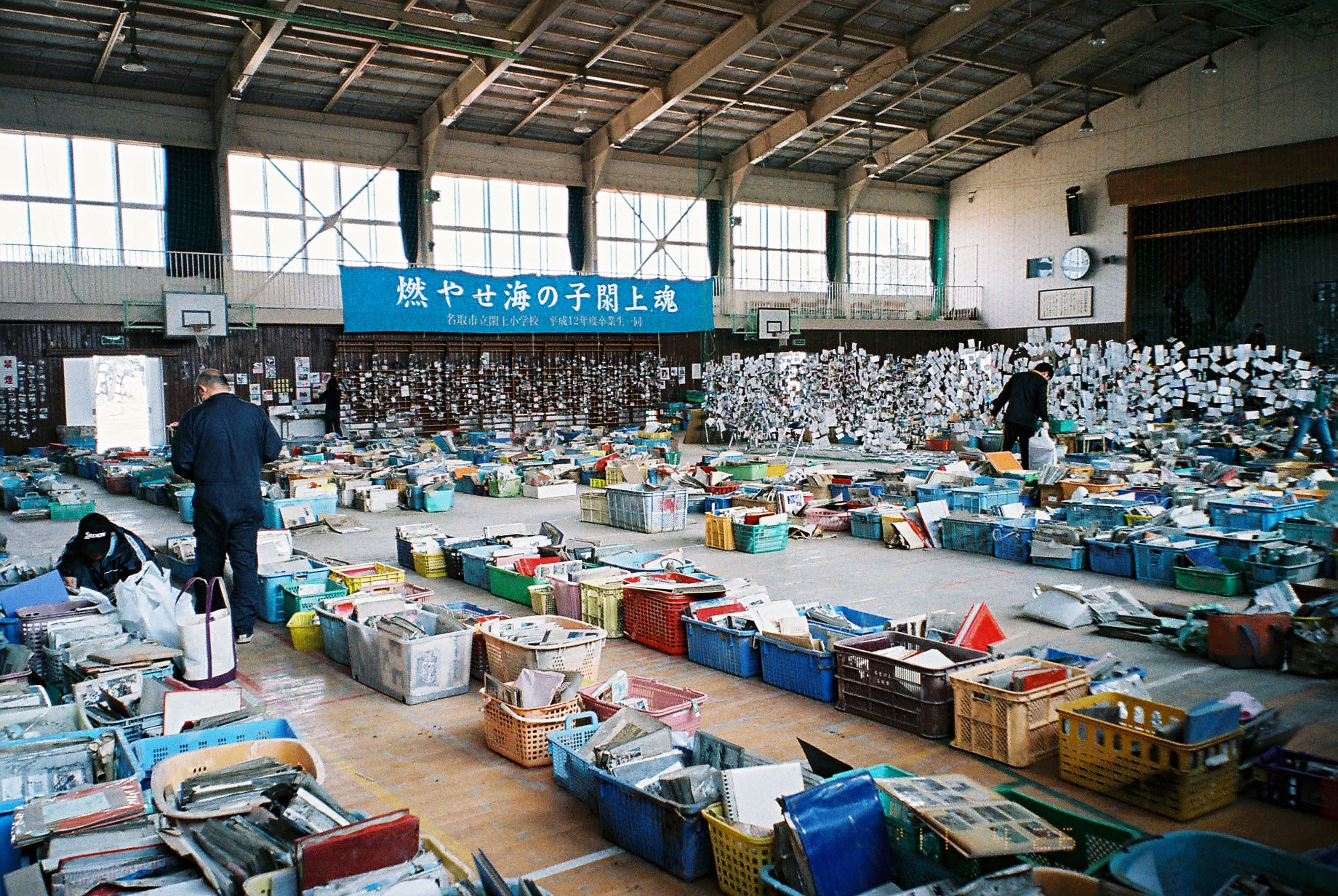

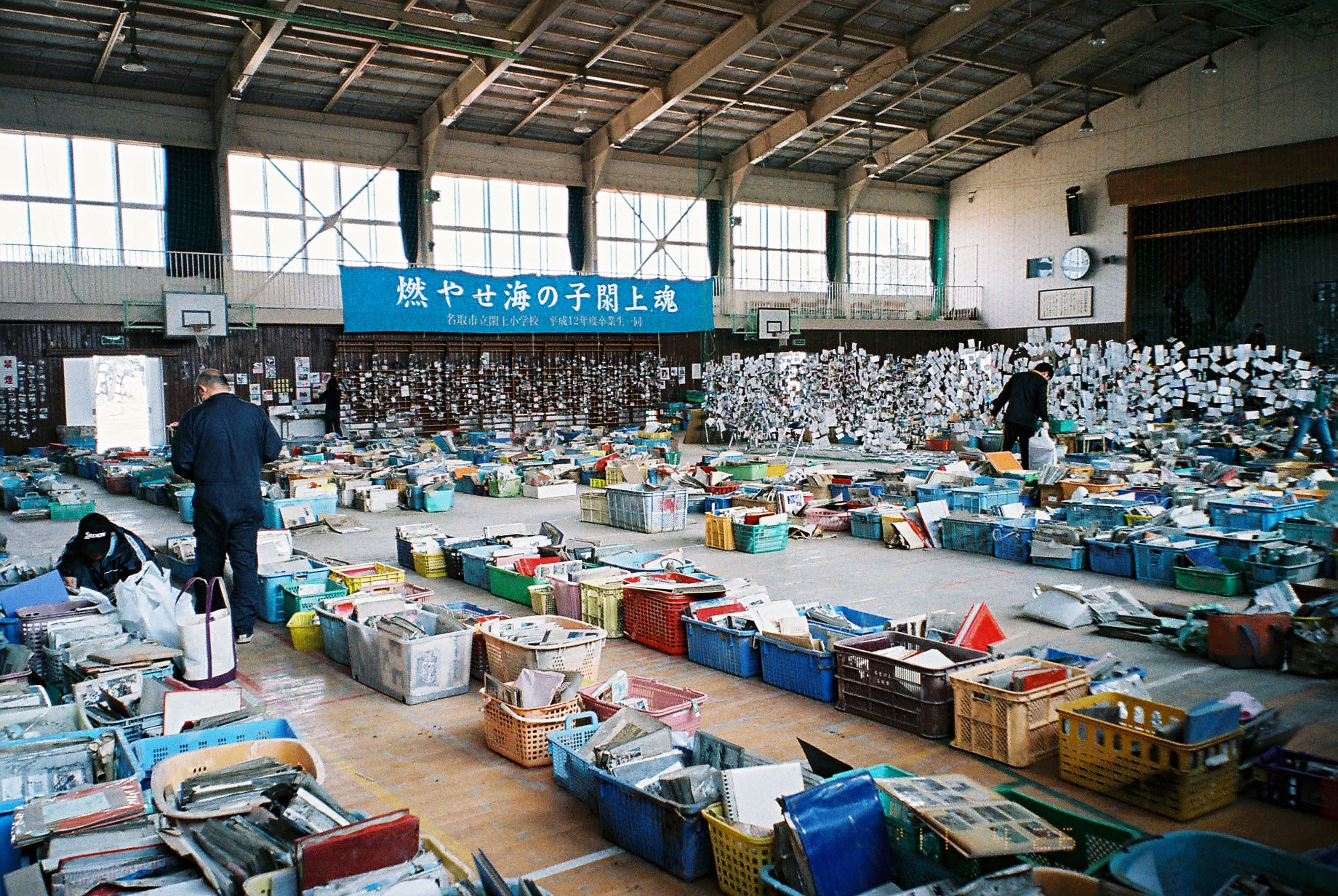

Every town along the coast appeared to have the same idea: when there were no more bodies to pull from the wreckage, they pulled photos. Volunteers called themselves the Memory Hunters.

As the communication lines were re-established, volunteers across the region realised they had all become Memory Hunters. They were bound together by the same comforting activity. “Rescuing photos, washing them, or trying to find their owners, all these activities united people,” Yoko says.

At that point, Japan’s traditional appreciation for photos combined neatly with a culture that places a special importance on returning objects to their rightful owners. In Tokyo, for example, the police say that 80% of lost mobile phones are returned and more than 60% of wallets — often within the same day.

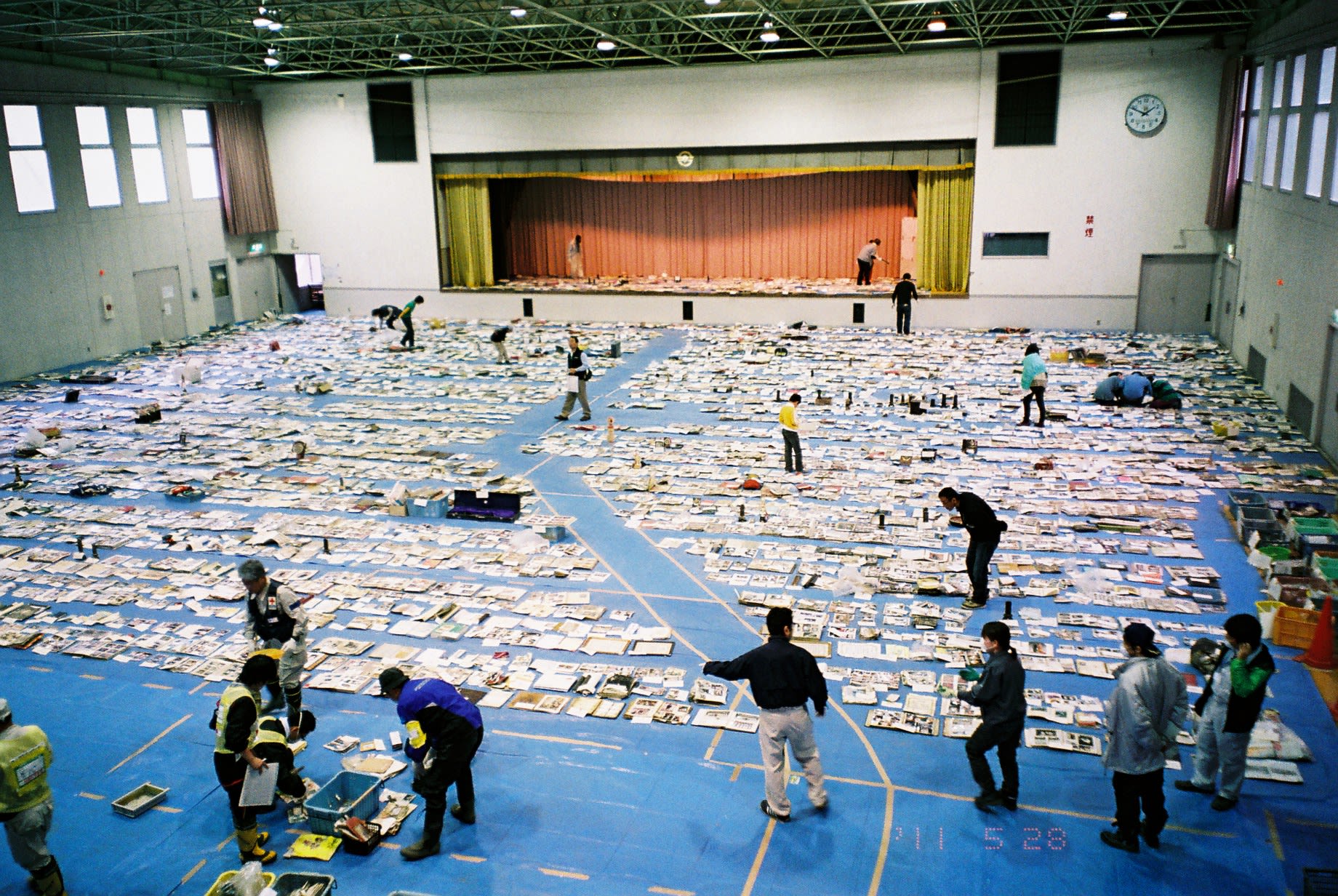

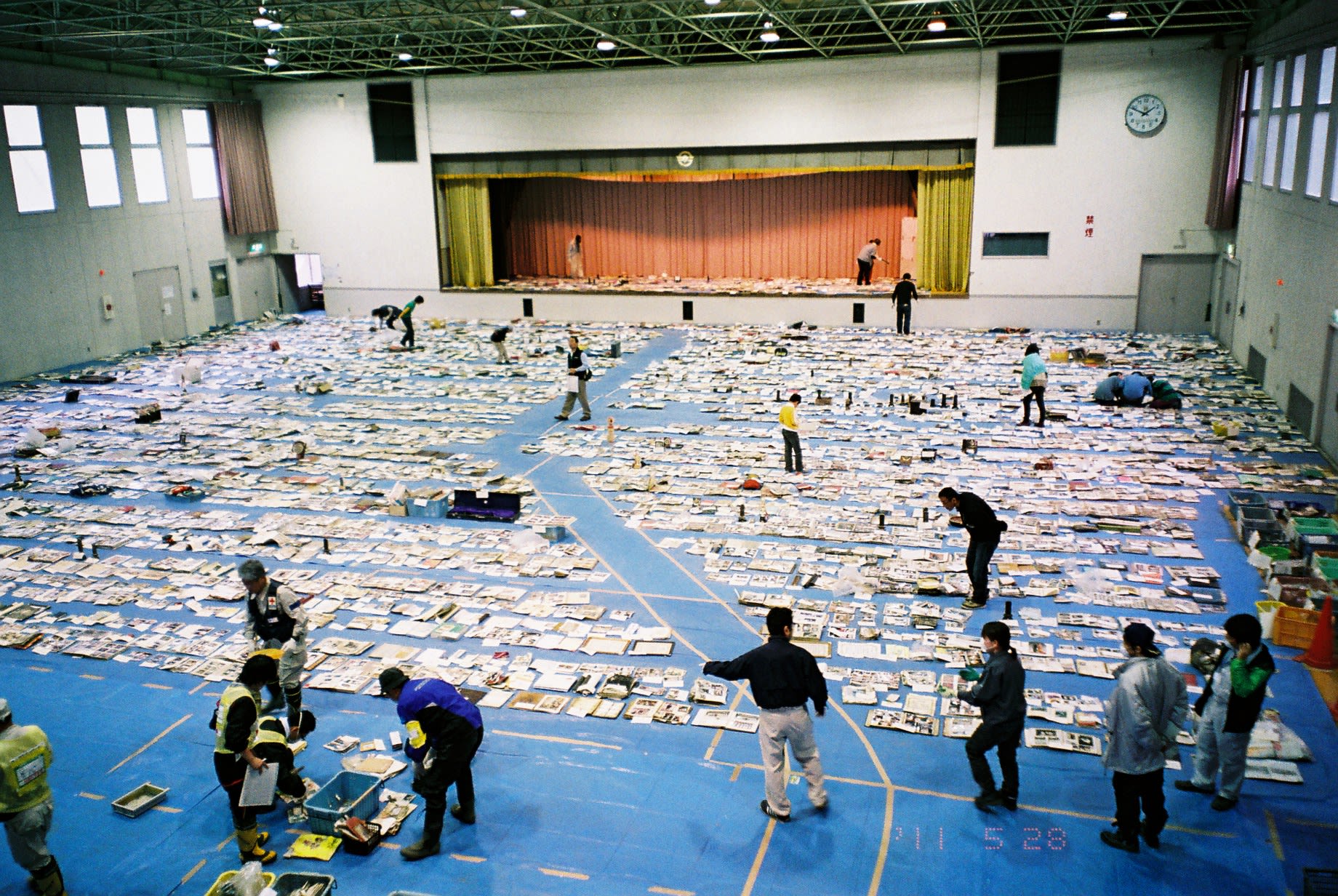

At first, it was thought that the photos were being saved so that those who were missing after the tsunami could reclaim them. But as the death toll grew, and it became clear that those who were missing probably wouldn’t return, the project became a way for those left behind to hold onto the memories of those who were gone. Volunteers formed surprisingly efficient assembly lines - painstakingly cleaning the waterlogged, mud-caked photos, and pegging them up to dry inside small tents.

Yuichi urged Fujifilm to make simple advertisements that would reach people across the tsunami zone, explaining that photos could be saved if they were washed in the right way. Other companies pitched in too, as corporations tried to find ways they might be able to help. A national effort was born.

That effort soon included overseas volunteers too. Becci Manson, originally from northern England, was working in New York when the tsunami struck. As one of the world’s top photo retouchers, Becci had forged a career working on fashion and advertising photographs by the likes of Rankin and Annie Leibowitz. But she put that work on hold to pitch in as a volunteer with the disaster relief charity, All Hands and Hearts. Two months after the tsunami, she was on the ground in Rikuzentakata, not far from where Tomomi Shida’s house once stood. Initially she was just expecting to lend muscle as an ordinary volunteer.

“We dug the mud out of people’s homes or helped clear the rubble from their land. We cleaned a factory which had fish in storage when the tsunami hit. They were just sitting there, in the dock area, rotting in the sun.”

Everything changed for Becci the day she went to help clean up an onsen - a Japanese bathing house. When she arrived, she saw that it was doubling as the storage site for thousands of salvaged photographs which had been stuffed in plastic bags. They, too, were rotting.

“It was one of those eye-opening moments,” Becci says, when she saw some survivors crying after seeing their photos had been damaged. Instantly, she realised that she had the perfect skill set to step in and fix them.

She issued a call to other professional retouchers she knew, asking them to pitch in. Within weeks she had 500 people from Sweden to New York lined up, ready to smooth over the smeared photographs and to make them look new again. A thousand volunteers on the ground worked on site to clean the photos too.

It was rewarding work, but it came with huge pressures as well.

“The drivers working with the volunteers would come in and look through the photos that had been cleaned because they were local guys,” Becci says. “One guy noticed his friend in the pictures with the friend’s twin daughters. The girls were less than one year old when the tsunami hit and they lost one of the daughters. So we dug through and found as many photos as we could of the kids so they could have them.”

The stories mounted. One woman lost all her relatives and was left with nothing but seven photos from a school trip. Another photo, featuring a girl’s elaborate kimono, needed to be almost entirely rebuilt. The whole process took days, with one retoucher painstakingly copying the embroidered design from a similar image so he could be certain it would be accurate.

Whereas Becci’s professional career involved “making the perfect even more perfect”, her biggest challenge with the Japanese photos “was to restore the photos to how they were meant to be. You don’t want to destroy the memory for someone by ruining a picture in some way”.

One day Tomomi Shida, the survivor from the obliterated town of Ofunato, came to see Becci. She brought the family portrait that had been salvaged, the one with her husband and two boys.

“We used different pieces from her photos to create a whole one,” Becci says, still marvelling at what a technically difficult fix that was. “We gave the finished photo back to her on her son’s birthday and I remember she was so happy, she cried. It was the one thing her son could hold onto that wasn’t new, and had existed before the tsunami took everything.”

The photo hangs in the bedroom Tomomi shares with her husband now.

“I had given up,” she remembers, “I thought the complete photograph was something that was already gone but then it came back to me.

“I lost all my belongings but I still have a record of my children’s growth."

Photo cleaning projects continued along the coast. In the city of Rikuzentakata, where Becci’s time in Japan was coming to an end, the cleaned photographs were beginning to pile up. That presented a new organisational hurdle: matching photos with their owners. The project was growing in scope. Unclaimed personal objects, like school backpacks and artworks, were also being salvaged and cleaned in hopes that they, too, would be reclaimed. It was clear that someone efficient needed to take control. Enter Mari Akiyama, a disaster agency worker tasked with managing the project's next phase.

“Once we had washed the photographs, we put them into albums," she says. "We began to show people what we had.”

These first events were simple affairs: albums and individual photos were spread out on the ground on blue plastic sheets.

The process continues 10 years on, and Mari still leads it.

But now, the system is much more sophisticated: Mari is in charge of a well-organised library of lost things, known as the Sanriku Archive Disaster Mitigation Center. The collected objects have been carefully sorted into groups — school diplomas on one shelf, wooden sculptures on another. Some are wrapped in cellophane. It looks a bit like a shop until it becomes clear that the owners of many of the objects might have died 10 years ago. It’s also possible the object's owners are still alive and simply haven’t realised their belongings are still waiting to be reclaimed.

“We don’t actually know what these photos or objects mean to people,” Mari explains. “The items only gain value when they’re returned to the people who might cherish them, who understand their original brilliance.”

Once a month, the centre creates pamphlets displaying some of the orphaned photos and objects, distributing them in doctors’ offices and hair salons, hoping they’ll be identified. Sometimes Mari and her colleagues will take a slew of photos to Tokyo, where many of the survivors have relocated, and they’ll hold a mass viewing event there.

“There are many people who return again and again, especially in Tokyo,” Mari says. “There are some cases where a body has never been found, so the survivors are trying to find even one or two belongings of the deceased.

One woman sifted through random photos for nine years until she found a single image of her missing husband. Another family lived in a trailer beside the centre for days in hopes of finding something familiar. Another time, an 80-year-old woman spotted a tiny photograph from her school days. She lit up when she saw the photo, Mari says, and suddenly started to recall school trips, and the teachers she’d known decades before.

And then, there are the people who simply can’t bear to look. Not yet. For them, Mari acts as a guardian of sorts.

“Whenever we’re mentioned on the television, there are people who call in straight away to tell us they’re still struggling,” she quietly explains. “Those people say that on the surface, they’re smiling, but actually they cry every day. They’re not comfortable looking at the photographs yet, so they ask us to hold on until they’re ready.”

But the centre is in danger. The city council has told them they’re probably going to lose their funding, so Mari has been forced to solicit donations to keep the Sanriku Archive open. She’s returned about 200,000 photos so far, but there are still 186,000 unclaimed pictures and more than a million objects in the library.

In other cities, photo centres have already closed their doors. In keeping with Japanese tradition, all the saved photographs are taken to a shrine and burned. “They’re given back to the dead,” Yuichi, the former manager from Fujifilm, explains.

Still, the drive to save photos, to clean them and to return them to their rightful owners continues. When Becci Manson returned to the US, she was asked to start photo rescue projects after several major US storms.

But one thing that struck her after the tsunami project was how much the photos helped people who were suffering with mental health issues after the disaster.

Family photos are different from almost everything else. They have an emotional pull that can’t be matched, especially after something terrible has suddenly taken people away.

Becci says the subsequent suicides by survivors of the disaster shows how crucial it was to take mental health seriously.

“People started mentioning the photographs over and over again," she says. "Having the photos helped them to get back some sense of their history and their normality.”

The photographs that were carefully washed and fixed are now, in turn, helping their owners to become whole again.

NB - Some of these photos were supplied to the BBC with slight pixelation

Credits

Author: Celia Hatton

Photographs: Becci Manson, All Hands and Hearts, Mari Akiyama from the Sanriku Archive Disaster Mitigation Center, Fujifilm

Translation and production help: Emily Yui

Editor: Sarah Buckley

OnlineProducer: James Percy

Published March 2021

More Long Reads

The three orcas causing havoc in the Atlantic