The end of Gaza’s most beautiful neighbourhood

Around noon on Friday 20 October, the residents of the upscale Gazan neighbourhood of al-Zahra stood in front of the rubble and dust that used to be their homes.

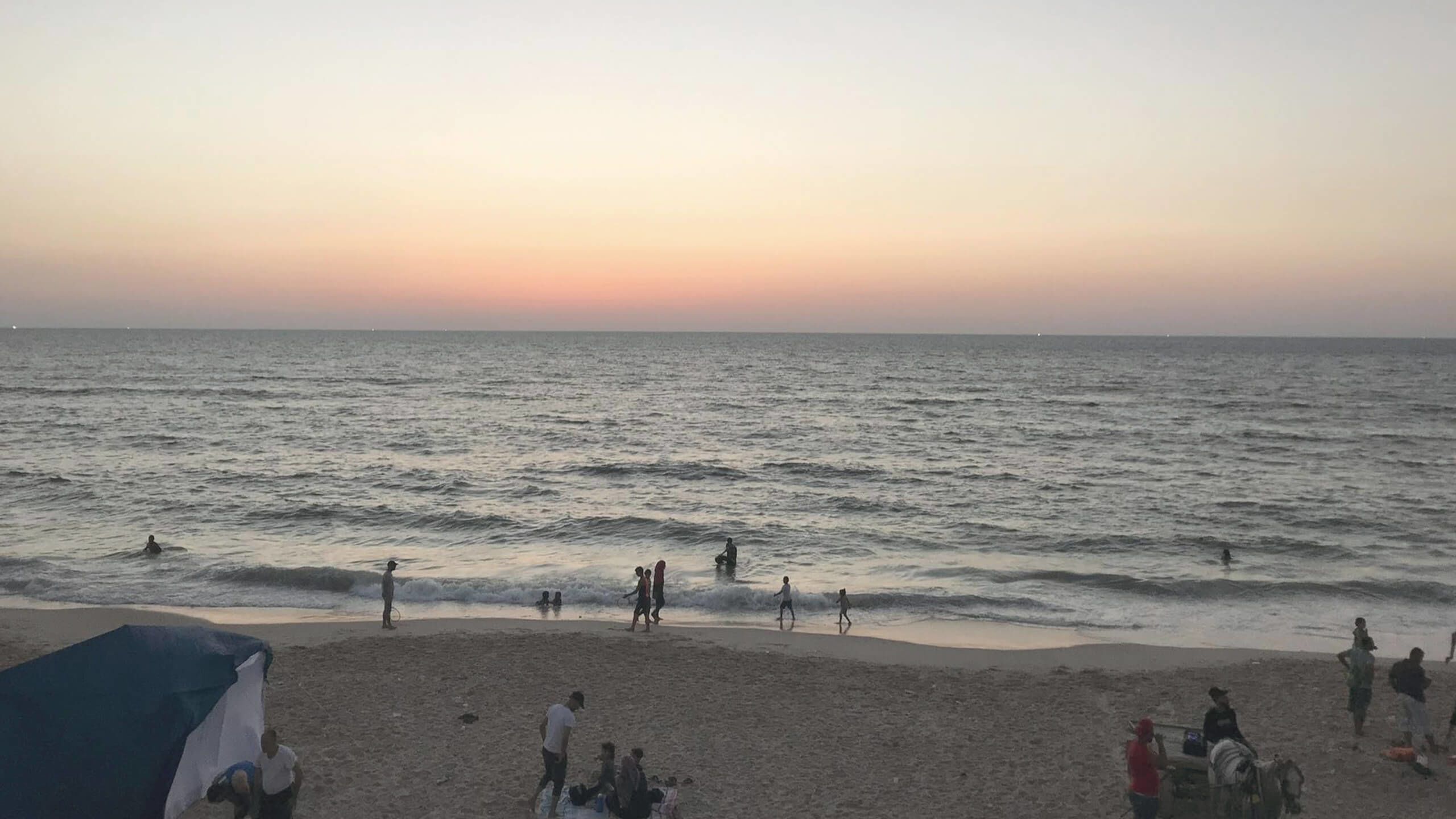

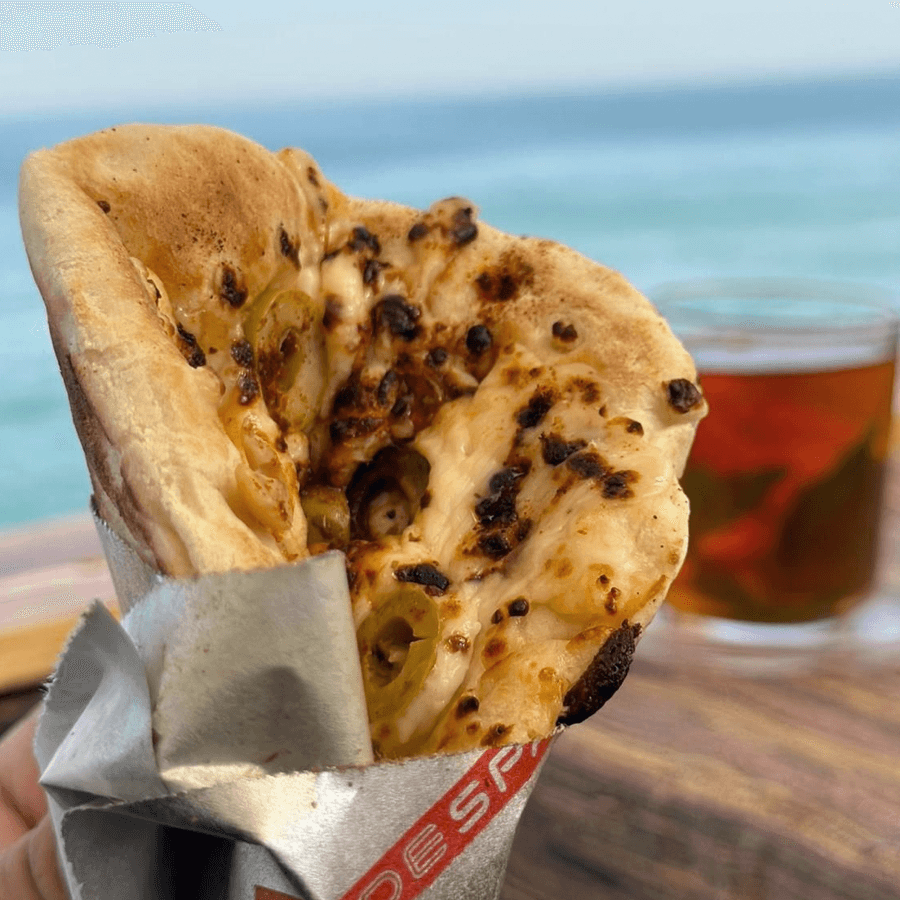

Fridays were supposed to be special: the Islamic day of prayer marks the start of the weekend and in al-Zahra it meant falafel and hummus, coffee and tea, all served in spacious family apartments or villas by the Mediterranean Sea. Residents here knew they were luckier than most in Gaza.

But overnight, Israeli bombs had flattened 25 apartment blocks, home to many hundreds of people. Israel had been bombing Gaza for days in response to the Hamas attacks of 7 October, but al-Zahra had not been hit until now.

Some of those who lived here - among them doctors, lawyers, academics, fashion designers and entrepreneurs - tried to stay and survive in the ruins, but most packed up what little they could salvage and dispersed across the Gaza Strip.

Hana Hussen, who grew up in al-Zahra, followed the news with horror from hundreds of miles away in Turkey, where she had moved two years ago. In a hurried phone call that day, she rang her family to check they were safe.

She told them she loved them.

Then the line went dead.

"Thank you for asking. We are still alive."

The residents of the destroyed apartment blocks had been sheltering from the bombs in a nearby university thanks to the efforts of local dentist Mahmoud Shaheen who led a mass evacuation of his neighbours. The BBC told the story earlier this week of how he received a dawn phone call from an Israeli intelligence agent warning him that the blocks would be bombed.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) told us it was “unable to answer specific operative questions” when asked about its decision to strike al-Zahra’s residential blocks. Hamas was attacking Israel from across the Gaza Strip and had “embedded itself in civilian infrastructure”, it added. It has not named any Hamas operative killed in the strikes on al-Zahra, and it is believed that nobody died.

Israel says its strategy has been to root out Hamas, which it accuses of operating in the heart of civilian communities - and that it takes steps to mitigate civilian casualties, such as the phone call we reported Mahmoud had received instructing him to evacuate the neighbourhood.

The agent who had called the dentist also told him: “We see things you do not see.”

Mahmoud’s neighbours may have escaped alive but they did not all survive what was to come.

The BBC has spent two weeks talking to several families from the area, both established residents as well as younger, ambitious newcomers.

They told us about how they had grabbed whatever they could from their homes, watched those homes explode in front of their eyes, and then dispersed around Gaza to an uncertain fate. From makeshift shelters and temporary homes across the strip, residents wanted to tell the story of the life and demise of a neighbourhood they loved.

Our communications have been over broken calls - sometimes with bombs sounding in the background - and sporadic WhatsApp messages. People cut conversations short to run or seek shelter. In some cases, we have lost contact for days at a time.

After a recent communications blackout during intense Israeli strikes on the strip, one al-Zahra resident eventually left a short message: “Thank you for asking. We are still alive.”

Our conversations show that not everyone who left al-Zahra survived. Among those reported killed are a young body-builder from a local gym whose last words to a friend, according to social media posts, were: “It’s all gone.”

The Hamas-run health ministry says more than 10,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza since the start of the war, over a third of them children.

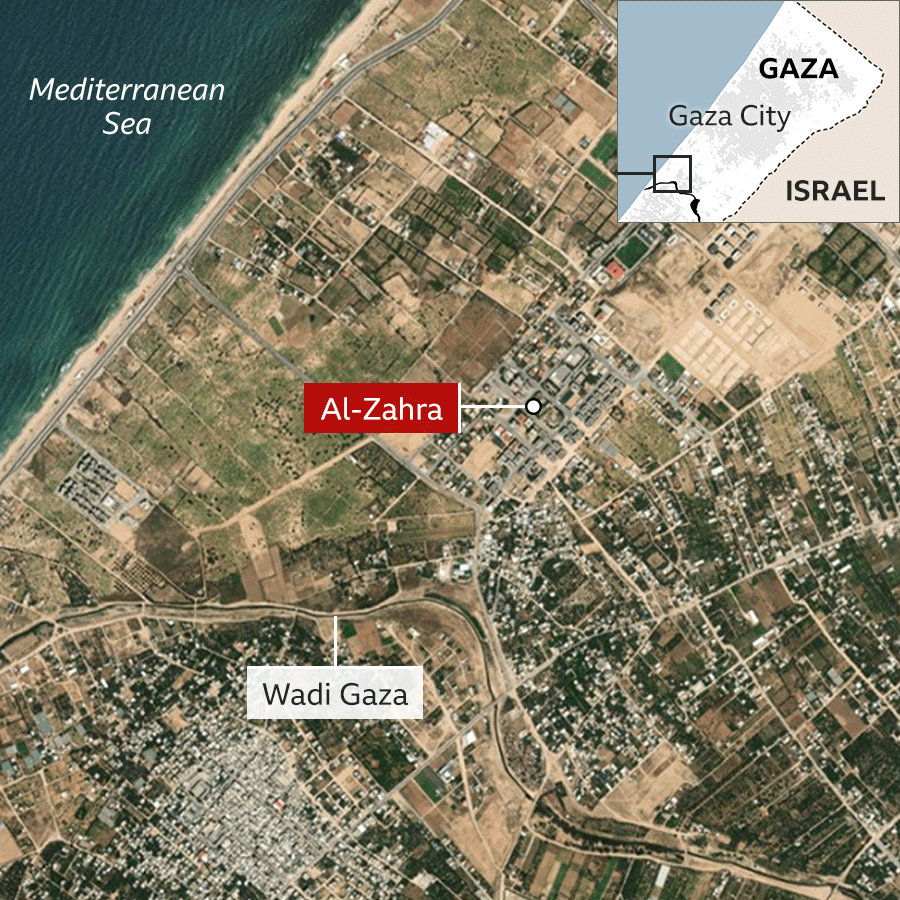

The Gaza Strip is densely populated with high levels of poverty and tight controls on entering and leaving. But al-Zahra was a neighbourhood of large homes and bright outdoor spaces, of groves with almonds and figs, of sports grounds and parks.

Al-Zahra was established in the 1990s by the late Palestinian Authority (PA) President Yasser Arafat as a place for staff and supporters. Locals say it still had strong connections with the PA, which is based in the occupied West Bank and is a bitter rival of Hamas.

It sits just north of the Wadi Gaza river - a point that Israel ordered civilians to move south of on 13 October. This followed days of bombing, Israel’s response to hundreds of Hamas gunmen rampaging across the border killing more than 1,400 people, mostly civilians including many children, and taking more than 200 hostages. The brutality of the attacks in southern Israeli villages and the massacre of young people gathering at a music festival has traumatised the nation.

Everyone we spoke to insisted that, to their knowledge, this area was as far removed from Hamas and its operations as it is possible to be in Gaza, which Hamas has ruled since 2007. “There was no military here,” one told us. “I don’t even think there were Hamas supporters living here.”

For Nashwa Rezeq, who had lived in al-Zahra for 18 years, it was the “greatest city of all”.

Heavily involved in neighbourhood committees and a local youth council, Nashwa has also been one of the keepers of a community Facebook group for more than a decade. If you ask her about a particular resident, she is likely to know them and perhaps even their phone number.

The Facebook page has about 10,000 followers. On the eve of the war there were posts about a billiards tournament at a local cafe and a message of congratulations to a graduating student.

Now the Facebook group is where they share updates on the destruction of their neighbourhood and mark the deaths of those who lived there. It has never before kept Nashwa this busy.

A recent post mourns a family killed in a strike that hit their Italian restaurant.

When war was declared, Nashwa headed south with her husband and four children, as the family always did during escalations. She gave her neighbour a key, asking them to tend her beloved house plants while she was gone.

Two days after the first bombings, her own building - the tallest in al-Zahra - was destroyed at dawn.

“Somebody called me and said ‘I just walked by your tower and it’s all on the ground’,” she recalls.

She describes her fifth-floor home as being “very big and spacious”. Her family bought it and improved it over the course of a decade - they had recently bought a new air conditioning unit, a television and furniture.

“A lot of people say it’s only money, but to me my home was my soul.”

Now in southern Gaza, she says her family are still in danger. “Three days ago, they bombed the house next to us. The smoke from that bombing suffocated us.”

Nashwa Rezeq with her son

Nashwa Rezeq with her son

The Gaza Strip is densely populated with high levels of poverty and tight controls on entering and leaving. But al-Zahra was a neighbourhood of large homes and bright outdoor spaces, of groves with almonds and figs, of sports grounds and parks.

Al-Zahra was established in the 1990s by the late Palestinian Authority (PA) President Yasser Arafat as a place for staff and supporters. Locals say it still had strong connections with the PA, which is based in the occupied West Bank and is a bitter rival of Hamas.

It sits just north of the Wadi Gaza river - a point that Israel ordered civilians to move south of on 13 October. This followed days of bombing, Israel’s response to hundreds of Hamas gunmen rampaging across the border killing more than 1,400 people, mostly civilians including many children, and taking more than 200 hostages. The brutality of the attacks in southern Israeli villages and the massacre of young people gathering at a music festival has traumatised the nation.

Everyone we spoke to insisted that, to their knowledge, this area was as far removed from Hamas and its operations as it is possible to be in Gaza, which Hamas has ruled since 2007. “There was no military here,” one told us. “I don’t even think there were Hamas supporters living here.”

For Nashwa Rezeq, who had lived in al-Zahra for 18 years, it was the “greatest city of all”.

Heavily involved in neighbourhood committees and a local youth council, Nashwa has also been one of the keepers of a community Facebook group for more than a decade. If you ask her about a particular resident, she is likely to know them and perhaps even their phone number.

The Facebook page has about 10,000 followers. On the eve of the war there were posts about a billiards tournament at a local cafe and a message of congratulations to a graduating student.

Now the Facebook group is where they share updates on the destruction of their neighbourhood and mark the deaths of those who lived there. It has never before kept Nashwa this busy.

A recent post mourns a family killed in a strike that hit their Italian restaurant.

When war was declared, Nashwa headed south with her husband and four children, as the family always did during escalations. She gave her neighbour a key, asking them to tend her beloved house plants while she was gone.

Two days after the first bombings, her own building - the tallest in al-Zahra - was destroyed at dawn.

“Somebody called me and said ‘I just walked by your tower and it’s all on the ground’,” she recalls.

She describes her fifth-floor home as being “very big and spacious”. Her family bought it and improved it over the course of a decade - they had recently bought a new air conditioning unit, a television and furniture.

“A lot of people say it’s only money, but to me my home was my soul.”

Now in southern Gaza, she says her family are still in danger. “Three days ago, they bombed the house next to us. The smoke from that bombing suffocated us.”

“A lot of people say it’s only money, but to me my home was my soul.”

Her children keep asking why they couldn’t have brought the new air conditioning unit and television with them when they fled al-Zahra. They also keep asking when they can go home and collect their toys.

For Nashwa, it’s her houseplants: “I loved all of them.”

University professor Ahmed Hammad, who lived in a building close to Nashwa, was another established member of this community. He was one of those who chose to stay after the strikes.

A media and communications professor in his 50s at a university to the north of the neighbourhood, Ahmed is eager to send his research papers to us and talks proudly about his six children, aged eight to 27.

“One of them is a dentist, one of them works in IT, one of them studied English literature at university. The other three are still at school,” he says.

When we spoke on the phone last month, Ahmed and his family were sheltering at their al-Zahra home, now without doors or windows. No longer able to go to work or school, they spent their time searching for wood to burn so they could cook. They stayed as they were too frightened to evacuate, worrying that they would be caught in strikes while moving south.

But on the night of 27 October, Israel intensified air strikes and expanded its ground operations - and we lost contact with Ahmed. Days later, he got in touch to say they had left their neighbourhood after a “very, very tough night” and even worse morning.

He describes dodging “continuous bombing” on the journey south.

“Every time a bomb landed, we lay on the ground.”

Media professor and father of six, Ahmed

Media professor and father of six, Ahmed

Her children keep asking why they couldn’t have brought the new air conditioning unit and television with them when they fled al-Zahra. They also keep asking when they can go home and collect their toys.

For Nashwa, it’s her houseplants: “I loved all of them.”

University professor Ahmed Hammad, who lived in a building close to Nashwa, was another established member of this community. He was one of those who chose to stay after the strikes.

A media and communications professor in his 50s at a university to the north of the neighbourhood, Ahmed is eager to send his research papers to us and talks proudly about his six children, aged eight to 27.

“One of them is a dentist, one of them works in IT, one of them studied English literature at university. The other three are still at school,” he says.

When we spoke on the phone last month, Ahmed and his family were sheltering at their al-Zahra home, now without doors or windows. No longer able to go to work or school, they spent their time searching for wood to burn so they could cook. They stayed as they were too frightened to evacuate, worrying that they would be caught in strikes while moving south.

But on the night of 27 October, Israel intensified air strikes and expanded its ground operations - and we lost contact with Ahmed. Days later, he got in touch to say they had left their neighbourhood after a “very, very tough night” and even worse morning.

He describes dodging “continuous bombing” on the journey south.

“Every time a bomb landed, we lay on the ground.”

He describes dodging continuous bombing on the journey south.

Back in Turkey, Hana stayed glued to her phone waiting for an update from her family.

As she waited, she told us stories about what she called “the most beautiful, warmest place in the world”.

Residents of al-Zahra congregated on the beach and filled the main street leading there at sunrise and sunset. On Fridays, Hana and her friends would go there to share jokes and stories from the week, she says.

In a sign of how much the war changed life here, Hana says that she started receiving “haunting” messages from those same friends - one asking if Hana would look after her children if she died, others asking for advice on “alternative options for feminine hygiene products”. Another wished they had clean water to drink.

After many days of waiting, Hana finally made contact with her family, including her brother Yahya, whom she describes as her soulmate.

Yahya was among a new generation of entrepreneurs in al-Zahra. The 30-year-old fashion designer prefers to talk about his former life instead of his current overcrowded accommodation just south of the neighbourhood, where he walked with his family over several hours after their home was destroyed.

He remembers the sound of birds as he looked out over the neighbourhood from the roof of his family’s apartment building.

Mohamed outside his destroyed apartment

Mohamed outside his destroyed apartment

“Our home is the street now. Everything was destroyed.”

People often posted videos from al-Zahra’s rooftops. Some show spectacular colours as the sun set.

“All those things made us feel delighted,” Yahya says via WhatsApp.

Listing some of his favourite things about his neighbourhood, Yahya writes in a string of messages: “The lights at night. The sea. It’s a peaceful and elegant city.”

Now, he sometimes ends WhatsApp conversations abruptly. “Can I go now because ther [sic] bomb near of me,” he says in one message.

He left al-Zahra with two bags containing an iPad, documents, a hoodie, a water bottle, his passport, chocolate, and a first aid kit. He was forced to leave his intricately crafted designs - his fabrics, dresses and skirts - behind.

"And sewing machines. And a lot of beautiful memories," he says.

Cousins Ali, 28, and Mohamed, 25, are also young entrepreneurs in the city, and had busy jobs in al-Zahra as a pastry chef and cafe owner respectively. Both lived in the row of buildings destroyed on 19 and 20 October.

They had invested a lot of money in building a life there. Ali got married earlier this year, and spent $6,000 on new furniture that was being kept at the family home, where he and his pregnant wife were staying.

His family moved here from Gaza City during the 2014 war between Hamas and Israel, thinking it was “the safest place“ to be.

Last month they prepared bags with two sets of clothing in, ready to grab if they needed to flee. “One bag for my mum, one bag for my brother, one bag for my wife,” he says.

On 19 October, the family picked up those bags and left everything else behind. When bombs hit their building, Ali says all of the losses were doubled - he and his wife’s new furniture was destroyed alongside his parents’ possessions. Two fridges, two washing machines, two sofas.

Mohamed says his dad had only recently made the final payment on their family home, when they too evacuated that night. “He finished the payment for the flat and now the flat is gone,” he says.

He now spends his days looking for water: “There is no time to rest.”

He misses the cafe he ran on the grounds of the university, with its pool table and painting of US rapper Tupac Shakur on the wall. He misses going to the gym every day. But mostly he misses his friends. “We’d be joking, laughing. We’d sit together until midnight.”

Journalist Abdullah al-Khatib says his extended family also lost four homes in the strikes.

He says his son keeps asking when he’ll be able to go home and play with his friends in the park. But he may never be able to return.

“Our home is the street now. Everything was destroyed,” he says.

People often posted videos from atop al-Zahra’s rooftops. Some show spectacular colours as the sun set.

“All those things made us feel delighted,” Yahya says via WhatsApp.

Listing some of his favourite things about his neighbourhood, Yahya writes in a string of messages: “The lights at night. The sea. It’s a peaceful and elegant city.”

Now, he sometimes ends WhatsApp conversations abruptly. “Can I go now because ther [sic] bomb near of me,” he says in one message.

He left al-Zahra with two bags containing an iPad, documents, a hoodie, a water bottle, his passport, chocolate, and a first aid kit. He was forced to leave his intricately crafted designs - his fabrics, dresses and skirts - behind.

"And sewing machines. And a lot of beautiful memories," he says.

Cousins Ali, 28, and Mohamed, 25, are also young entrepreneurs in the city, and had busy jobs in al-Zahra as a pastry chef and cafe owner respectively. Both lived in the row of buildings destroyed on 19 and 20 October.

They had invested a lot of money in building a life there. Ali got married earlier this year, and spent $6,000 on new furniture that was being kept at the family home, where he and his pregnant wife were staying.

His family moved here from Gaza City during the 2014 war between Hamas and Israel, thinking it was “the safest place“ to be.

Last month they prepared bags with two sets of clothing in, ready to grab if they needed to flee. “One bag for my mum, one bag for my brother, one bag for my wife,” he says.

On 19 October, the family picked up those bags and left everything else behind. When bombs hit their building, Ali says all of the losses were doubled - he and his wife’s new furniture was destroyed alongside his parents’ possessions. Two fridges, two washing machines, two sofas.

Mohamed says his dad had only recently made the final payment on their family home, when they too evacuated that night. “He finished the payment for the flat and now the flat is gone,” he says.

He now spends his days looking for water: “There is no time to rest.”

He misses the cafe he ran on the grounds of the university, with its pool table and painting of US rapper Tupac Shakur on the wall. He misses going to the gym every day. But mostly he misses his friends. “We’d be joking, laughing. We’d sit together until midnight.”

Journalist Abdullah al-Khatib says his extended family also lost four homes in the strikes.

He says his son keeps asking when he’ll be able to go home and play with his friends in the park. But he may never be able to return.

“Our home is the street now. Everything was destroyed,” he says.

Mahmoud, the dentist who took the evacuation call, is now volunteering at a medical centre in central Gaza.

“I smell the most horrible smells. You are not washing and there are 130 people with you,” he says.

Mahmoud says he feels fortunate to have enough money for the inflated prices of everyday items. One of Mahmoud’s close friends has remained in a villa in al-Zahra, and the dentist recently sent flour to him so he could make bread.

But those same items are in increasingly short supply.

“Today I went to all the shops looking for lentils… and I don’t want to exaggerate, I entered at least 40 shops to ask for lentils and I couldn’t find any,” he says. “One shopkeeper told me, ‘Don’t waste your time.’”

Mahmoud says he hopes to go back to al-Zahra after the war is over. “I hope God will let us survive and then we will try to fix things.”

The IDF says Hamas continues to operate from across the Gaza Strip. It added: “As part of the IDF's mission to dismantle the Hamas terrorist organisation, the IDF has been targeting military targets across the Gaza Strip. Strikes on military targets are subject to relevant provisions of international law, including the taking of feasible precautions to mitigate civilian casualties.”

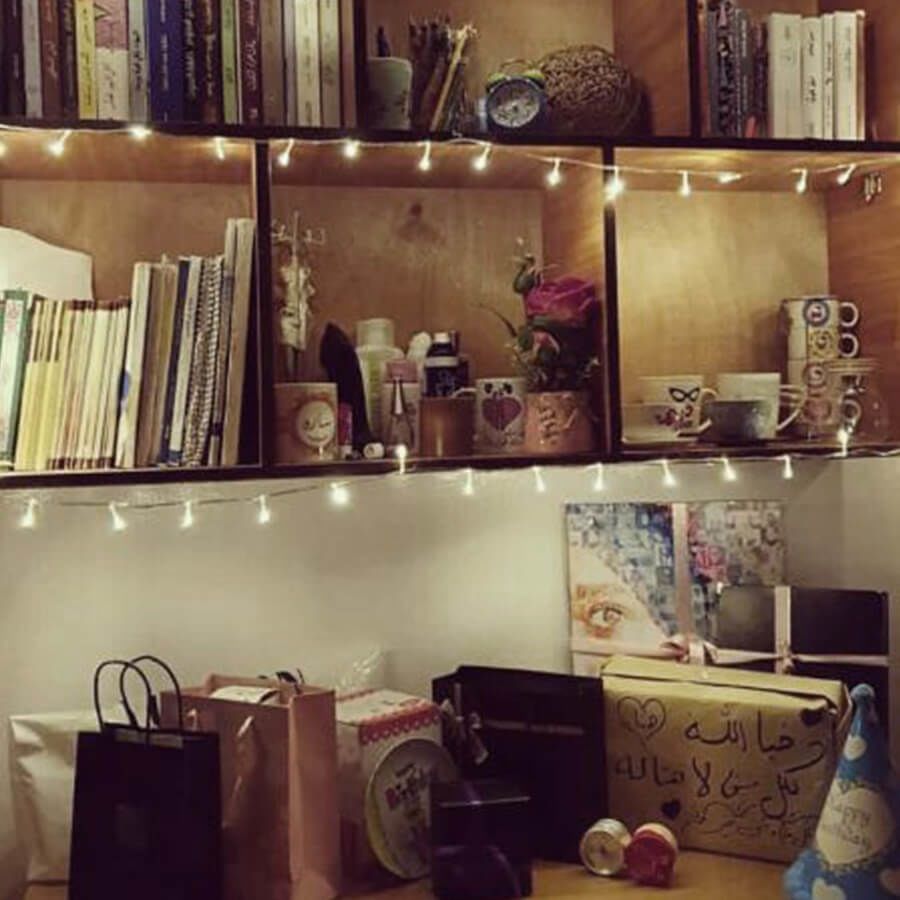

Hana last went to al-Zahra five months ago, not knowing it would be the last time she would see her home.

“If I had known, I would have… bade farewell to the walls of my room, which I love, and which have witnessed moments of joy and sorrow in my life.

“I would have taken many of my belongings that carry memories of dear moments,” she says.

“They left us with nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

“They left us with nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

More on Israel-Gaza war

- From Israel: Pain still raw a month after Hamas attacks

- Kibbutz Be’eri: Hamas attack captured by mothers’ WhatsApp group

- Watch: The devastating effects of war on Gaza’s children

- More on al-Zahra: Gazan tells BBC about most terrifying call of his life

- Explained: Who are the hostages taken by Hamas from Israel?

- History behind the story: The Israel-Palestinian conflict

Photo credits: Getty Images, Reuters, EPA

Additional reporting: Muath Al Khatib and BBC News Arabic’s Dima Al Babilie

Edited by Samuel Horti