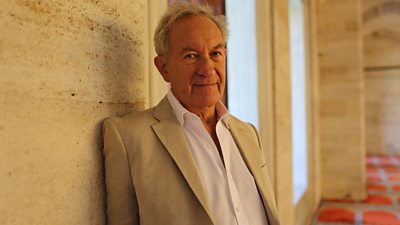

Introduction by Simon Schama, Writer, Presenter and Project Consultant

Half a century ago, in 1968, Kenneth Clark was in Paris, standing in front of the BBC cameras, asking, “What is civilisation? I don’t know… but I think I can recognise it when I see it”; then, turning to Notre-Dame behind him, he added: “And I’m looking at it now.”

Art should never be a bromide for discontent, but it can deliver things in short supply in our own universe of short attention span: attentiveness, thoughtfulness, contemplation, depth; illuminations that persist when the screen goes dark.

Then off he sailed into the majestic television series that brought millions to the mighty illuminations of European art. But somewhere off camera the Fifth Republic was falling apart; students were roaring protests and, when not buried in the Archives Nationales or dodging a light mist of tear gas in Montparnasse, I was among them. I was, in fact, part of the problem: by Clark’s lights, barbarically feckless youth, stoned on self-righteousness, threatening to storm the doors of “bourgeois” enlightenment.

So it’s with a sense of irony that Clark would doubtless have relished that at many points along the way in the past two years I too have found myself asking the same question or wondering whether it was even worth being put. But towards the end of filming, one particular work of art gave me the answer. It was by an artist Clark would not have heard of, though I like to think he would have felt the same way about her. She was 12-years old when she made her picture, living in Building L410, in the concentration camp of Theresienstadt, about an hour’s drive north of Prague. Like the other 15,000 children, Helena Mandlová had been taken from her family on arrival and put in horrifyingly overcrowded, disease-ridden barracks. But during the hours she spent as a pupil of her art teacher Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, one of the great unsung heroes of the history of art, Helena was free. Her collage, which you can see in the Jewish Museum at the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague, is a night landscape, as if seen in a dream. The white paper used for stars and mountains is office stationery; its heading, inverted by Helena so that it lies at the foot of her composition, German. The sheet is not some enumeration of transports east, one of which would carry Helena (like 90 per cent of the Theresienstadt children) to her death in Auschwitz, but simply some piece of dull bureaucratic supply of the kind needed by those who managed the efficient business of mass extermination. But for a moment, Helena had cleansed the sheet of its moral dirt. She had made art.

I am not someone who subscribes to the Romantic theory that torment and sorrow, whether of the artist or the world, are the necessary conditions of great art. Yet, without leaning on the scales of history, it has been striking how often a period of great creative energy either followed a period of calamity or was produced as a response to it. Art as redeemer from calamity was of course the leitmotif of Clark’s heroic narrative of European genius. It is a seductive story told with eloquent persuasiveness and in many respects not at all wrong.

So what could possibly be added by a new series? And of course the answer is the rest of the world. There are countless moments when contact between the European and the non-European world seeded a blossoming of cultural creativity. The most abrasive issue of our own time worldwide is precisely this relationship between connection and separation, and the history of art has not been unaffected by it. Mary Beard, David Olusoga and I instead try to give the wider truth an airing without, we hope, spoiling the view. Quite often, that truth can be one of fruitful connections. In one programme I look at the dramatic impact the availability of woodblock prints by Hokusai, Hiroshige and the rest had on painters like Monet, who collected more than 200 of them, and Van Gogh, who borrowed them from the dealer Siegfried Bing, and his brother Theo, who sold them.

These encounters are not necessarily the rule. There are plenty of instances where cultures take root and evolve in complete isolation from the rest of the world: the glories of the Maya being a spectacular case in point. In 1986, a sacrificial grave was discovered at Sanxingdui near Chengdu in Sichuan, in which, along with a mass of elephant tusks, a trove of bronze masks was discovered, some colossal, some gilt, which bore absolutely no relationship (except in the technology of their casting) to anything else seen in Bronze Age China.

Civilisations makes no pretence to being a comprehensive survey of world art. Each of the programmes, while delivering a feast for the eye, is driven as much by themes as by stories, and the questions that looking at masterpieces provoke. Art should never be a bromide for discontent, but it can deliver things in short supply in our own universe of short attention span: attentiveness, thoughtfulness, contemplation, depth; illuminations that persist when the screen goes dark. As close as we could get to the works of art, though, I am under no illusion that what we offer is any sort of substitution for being in their material presence. So the offering is by the way of an invitation: go, see, think. Let the exhilaration, the disturbance, the power and the beauty sink in. And if in the weltering storm of the trivial we can interpose some sense of what really matters in the array of things humans - the art animals - have fashioned, then, perhaps we will be judged to have done our job.

Simon Schama is a writer for the FT where a longer version of this article was published on 27.01.2018

Simon Schama biography

Simon Schama, CBE is University Professor of Art History and History at Columbia University, a Fellow of the British Academy and the Royal Society of Literature and Contributing Editor at the Financial Times.

He is the author of eighteen books which have been translated into 16 languages and the writer-presenter of fifty documentaries on art, history and literature for BBC Two and PBS. He was art critic for the New Yorker in the 1990s and won a National Magazine Award for his art criticism in 1996, published as Hang-Ups, Essays on Painting (Mostly). His film on Bernini from the Power of Art series won an International Emmy and his series on A History of Britain and The American Future. A History won Broadcast Critics Guild Awards. His art history work also includes Rembrandt’s Eyes, (1999) The Power of Art,(2006) and The Face of Britain (2015)

He has published a work of fiction, Dead Certainties: (Unwarranted Speculations) and his work for the theatre includes the stage adaptation of Rough Crossings (with Caryl Phillips) for Headlong Theatre, and in 2011, a short play for Headlong’s site-specific production about 9/11, Decade.

He won the NCR non-fiction prize for Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution; the WH Smith Literary Award for Landscape and Memory, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in the United States for Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution. His latest book, Belonging, volume 2 of The Story of the Jews was short-listed for the Baillie-Gifford Prize and was among The Economist Magazine’s Best Books of 2017. In 2011 he received the Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement and in 2015 the Premio Antonelli Feltrinelli in historical sciences from the Accademia nazionale dei Lincei in Rome.

He has delivered the Andrew W Mellon Lectures at the National Gallery in Washington DC in 2006 on “Really Old Masters: Infirmity and Reinvention”, and the Anthony Hecht Lectures in the humanities at Bard College on memory in contemporary art; and most recently the Jerusalem Lectures for the Israel Historical Society.

He curated the Government Art Collection exhibition Travelling Light at the Whitechapel Gallery and The Face of Britain exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2015, in conjunction with a 4 part television series and a best-selling book. His most recent book (2017) is Belonging. He has collaborated with Anselm Kiefer, John Virtue, Cecile B Evans and Damien Hirst on exhibitions and catalogue essays.

For the past year and a half he has been working on the BBC/PBS series on world art history, Civilisations, due to be broadcast in the spring of 2018.