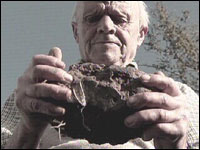

A MYSTERIOUS METAL | | Local farmer Dudley Coombe with his amazing find |

Switch on a lightbulb and it's there for all to see. Tungsten is one of the world's most-utilised metals, and although the Spanish are credited with its discovery, new evidence suggests that the Cornish may have got there first. Inside Out investigates. As one of the hardest elements in the periodic table with the highest melting point, tungsten is widely used to reinforce the tips of everything from drills and darts to bullets and shells. It is thanks to tungsten's use in the filament - and the discovery of electricity too - that we have such wonders as the lightbulb. The Spanish are credited with its discovery in 1783, but a new and important find suggests that Cornwall may have been the first to smelt tungsten. A mysterious findFarmer Dudley Coombe discovered what scientists are calling 'the find of a lifetime' - a lump of metal which has been nicknamed 'the Trewhiddle ingot.' Dudley discovered the ingot in the summer of 2003 while clearing out a ditch on his land, where he struck upon a pineapple-sized stone in the earth. "I was clearing a field which hasn't been ploughed within living memory, at least 100 years, and I came across this piece which I thought looked like a normal stone. "I managed to lift it and nearly fell flat on my face - I've never handled anything as small as that and as heavy." Investigation | | Dudley's son Vyvyan sent off a sample of the rock to be examined by experts |

Having carried it home and weighed it on an industrial strength spring balance, he discovered the ingot came in at an incredible 42lb (19kg) - the equivalent to eight bags of potatoes! On this discovery Dudley did what anyone might do - put it to work as a doorstop. And there it might've stayed but for a fortunate coincidence - Dudley's son Vyvyan happens to be a scientist. "We all wondered what it was, we thought it might be a meteorite but really had no idea why it was so dense. "I did what all good scientists do - I attacked it with an angle-grinder. "It mangled the grinder more than it mangled the object!" Vyvyan eventually managed to chip off a couple of pieces to send to the Natural History Museum, who revealed that the object was man-made, more than 150 years old, and more than 50% solid tungsten metal. The results prompted a frenzy of speculation in the scientific community. Ore-inspiring| Tungsten Facts | Periodic table symbol: W

Atomic number: 74

It has the highest melting point (3422 °C) of all metals

It has the lowest vapor pressure of all metals

It has the highest tensile strength at temperatures above 1650 °C of all metals

It is a very hard, heavy, steel-grey to white transition metal

It is found in several ores including wolframite and scheelite and is remarkable for its robust physical properties

The pure form is used mainly in electrical applications but its many compounds and alloys are widely used in many applications (most notably in light bulb filaments and in space-age superalloys)

Source: Wikipedia |

Tungsten ore, known as wolframite, is found all over Cornwall. The most famous of all Cornish wolfram mines, Castle-an Dinas, is only four miles away from where the Trewhiddle ingot was discovered. So if tungsten ore is "ten-a-penny" in Cornwall, then why should this ingot spark so much debate? Today tungsten is used in many modern-day appliances including microwave ovens and television sets, but at the time of the ingot's conception, over 150 years ago, its uses were unknown. In fact, miners went out of their way to avoid it. "The old miners regarded it as a confounded nuisance," explains mining expert Colin Bristow. "Wolframite and tin ore have the same density and they couldn't separate them." Back then, they couldn't reach anywhere near the 3000 degree temperature needed to melt tungsten, which prompted the question - how was the Trewhiddle ingot made? Accident's happenOne assumption put forward is that the ingot was nothing more than a by-product of repeated smeltings of tin slag contaminated with wolfram. "One possibility is that it built up to the point that a great lump of tungsten developed in the slag," explains Colin Bristow. "They would simply have dumped it as being of no value." But if this assumption were true, there would surely be similar tungsten ingots littered all over Cornwall. So far, the Trewhiddle ingot is the only one. So what is the other explanation? Unravelling the story | | Colin Bristow has another theory |

History has it that in 1783, the same year the Spanish recorded discovering tungsten, a mysterious German scientist appeared on the Cornish mining scene. Better known as the author of the Baron Munchausen stories, Rudolph Erich Raspe worked as chief chemist at Dolcoath mine. We know from his writings that he visited St Austell's Happy Union Mine and letters show that he had a detailed knowledge of tungsten. "Raspe was very interested in tungsten," reveals Colin Bristow. "In fact, Raspe himself wrote to Matthew Bolton, of "Bolton and Watt" fame, suggesting tungsten should be added to iron to improve the casting properties of anchors." Raspe's theory was ahead of its time and as such, his advice was ignored. Mind blowingLater that same year, one of the smelters at the Happy Union Mine lower blowing house caught fire. Could Raspe have been involved? "It's lovely speculation: Raspe visiting Happy Union, learning about this mysterious ore wolframite," muses Colin. "Unable to resist temptation to try and smelt it, perhaps he persuaded the manger of the lower blowing house to have a go. "He got so enthusiastic and got the temperature so high; it caused the whole place to burn down!" Leaving nothing behind except a smouldering tungsten ingot? Truth in the tale | | Mineralogist Ben Williamson examined the rock |

The Trewhiddle ingot is taken back to the Natural History Museum for further analysis. It seems Colin's dramatic speculation as to the ingot's creation, may remarkably be close to the truth. "In Cornwall they were highly skilled at tin production during the 17th and 18th Century," explains scientist Ben Williams, of the Natural History Museum. "It's highly unlikely they'd have made such a mistake. "It is far more likely, given the nature of this sample, that it was some attempt to produce tungsten metal." The discovery of the Trewhiddle ingot, its analysis and new theory have rocked (no pun intended) the scientific community. The ingot not only challenges the belief that the Spanish first discovered the metal, but also suggests that the metal's valuable properties were already known about too. Whether or not Dudley discovers more tungsten at the St Austell rainbow's end, he has already helped re-write mining history in Cornwall, Spain and indeed the world. |