Our Friends in the North

30 years on from the first episode of this groundbreaking drama, we take a closer look into the programme’s archive to reveal a time capsule of a turbulent era.

Our Friends in the North is a multiple award-winning nine-part BBC Two drama serial, telling the story of four friends from Newcastle from the 1960s to the 1990s. While its fictional events play out against the backdrop of an evolving Britain of the late 20th century, the story of its production is also one of great change – at the BBC.

Long development

There are thousands of papers in files from the series held by the BBC Written Archives Centre at Caversham in Berkshire, including some of the earliest print-outs of email correspondence you’ll find in the BBC’s collections.

These files make it clear that Our Friends in the North’s path to transmission would make a drama in and of itself. It had taken more than a decade for it to be successfully adapted by Peter Flannery from his own Royal Shakespeare Company play of the early 1980s.

There had been legal concerns due to Flannery basing some of the supporting characters on real people. When these worries started to ease through the early 1990s as some of those people died, in April 1994 assistant producer Nicola Shindler jokingly referred to Flannery in one memo as “the first serial killer whose motive was to get a drama made.” Earlier in the programme’s development, in 1990, consultations with the BBC’s legal department had dismissed the idea of setting Our Friends in the North in a fictional country as the events of the story “would make the country easily recognisable as Britain.” However, the BBC lawyer consulted had suggested setting elements of it “in Scotland” or “the distant past (1930s)” to try and provide suitable distance from reality.

There are also the usual fascinating titbits you get from such paperwork; paths not taken, actors’ names suggested, agents approached. It is a fun mental game to imagine the alternative world in which Mary, Nicky, Tosker and Geordie were played not by Gina McKee, Christopher Eccleston, Mark Strong and Daniel Craig, but instead by Helen Baxendale, Alan Cumming, Sean Pertwee and Paterson Joseph. Where the serial was directed not by Stuart Urban, Pedr James, and Simon Cellan-Jones, but by Danny Boyle.

A changing world

But actually, there’s another, bigger story told by these files. It’s the story of the BBC beginning to change from one approach to programme making to another. The start of a journey away from making and doing almost everything itself, to where it stands today as more of a ‘publisher broadcaster’; commissioning most of its dramas from outside producers.

Until the 1990s, the BBC had acted as a television production factory. But by the time of Our Friends in the North, many resources such as design, costume, lighting and various others were increasingly being put out to tender. Indeed, since the passage of the 1990 Broadcasting Act the BBC had even had a legal requirement for 25% of its programmes to be made for it by independent production companies.

This was not unique to the BBC. Such changes were happening at the big ITV companies as well and in many other industries. Hospitals, for instance, might once have employed their own catering or cleaning staff, but would now contract-out such services.

When Our Friends in the North was being made in 1994 and 95, the BBC’s in-house departments still existed but were now having to compete on a commercial basis. For example, for forty years the BBC had run their own set of film studios at Ealing, where productions made on film like Our Friends in the North would usually have been shot. This was as opposed to the videotaped shows made at BBC Television Centre.

But the BBC was at this point already in the process of shutting down its operation at Ealing, and Our Friends in the North demonstrates one of the reasons why. The production team had chosen to shoot the interior scenes at Bray Studios, the former home of the Hammer horror movies – because it was cheaper, although the series did use BBC film crews.

One foot in the past

Extensive use was made of other BBC departments, though, and the paperwork is peppered with references to them. There was much correspondence with the ‘Negative Checking’ team, to take one example, with many faxes going back-and-forth to make sure the names of fictional Newcastle businesses and the like didn’t clash with any actual names from reality.

Where the Our Friends production team was based also shows a foot in an older world. Its offices were in the BBC’s Threshold-Union House complex on Shepherd’s Bush Green in West London, where scores of drama programme teams had been based for more than thirty years. However, this was to the chagrin of producer Charles Pattinson, who had wanted to be based closer to the drama executives up the road at Television Centre.

That he couldn’t was down to space – one 1994 memo sets out that Our Friends in the North required “9 offices ideally in a very particular configuration, to house 3 teams and a Design team as well as producer, support staff, script editor, you-name-it.”

Pattinson also had to internally defend his series against a view some of his own superiors held, that programmes made for the BBC by independent companies were more economical than those made by the Corporation itself.

“The budget now stands at £750,671 per hour,” he explained in May 1994. “HowHigh the Moon [transmitted as Seaforth] from Initial Pictures has often been quoted to me as an example of an independent achieving period drama for a fraction of in-house costs but their budget approximates to £780K per hour.”

Viewer responses

Even though the files do contain the odd email, Our Friends in the North was made and shown in what was still mostly a pre-online world. 1996 was 11 years away from the arrival of the BBC iPlayer. Although home video recorders were prevalent, if you forgot to tape a programme or your recording went awry, you had no easy way of being able to see it.

The paperwork shows Pattinson pushing hard for what was called a ‘narrative repeat’ – each episode being transmitted again later in the week of its first broadcast, giving a chance for viewers to catch up. But this was turned down for reasons of cost – a far cry from iPlayer ‘box sets’.

Pattinson’s frustration at this perhaps explains why after the conclusion of Our Friends in the North, he responded positively to more than one viewer pleading for a copy of the final episode.

“Since it would be too far for you to come and view a cassette here and we currently have a couple of spare copies, I have decided to send you a cassette of Episode 9, as requested,” the producer wrote in reply to one such letter. “Can I please urge, however, that you return the tape to us as soon as possible to the address on the box.”

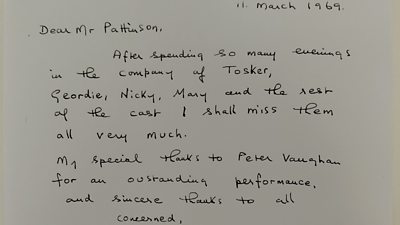

Several who wrote in said that they felt almost compelled to do so. How Our Friends in the North had, in some way, touched their lives and reflected their own experiences. “After spending so many evenings in the company of Tosker, Geordie, Nicky, Mary and the rest of the cast, I shall miss them all very much,” is a typical example of the sentiments often expressed; this from someone clearly so transported by the serial that they accidentally dated their letter ‘1969’ rather than ‘1996’.

However, the letters were not universally positive. “Good serial, shame about the boring use of disabled character ‘Patrick’,” wrote someone signing themselves as ‘A’. “How convenient he should die in the fourth episode. Doesn’t that just sum up society’s attitude towards us? You’d love us to just turn over and die. Tough – we ain’t going to.”

The view from the top

BBC Director-General John Birt sent a note to Managing Director of Network Television Will Wyatt suggesting, “we might look at the quality of historical research on our drama. There are too many lapses for my taste in the otherwise compelling Our Friends in the North.”

In reply, however, Wyatt pointed out that it was impossible to comment “without knowing which points,” Birt was referring to. “It is a fiction, albeit heavily based on history.” Birt seems to have accepted this, as the files also show that after Our Friends in the North had finished he invited cast and crew to a drinks reception at Broadcasting House to celebrate its success.

OurFriends in the North would stand the test of time as one of the most esteemed BBC dramas of the 1990s. 30 years on, it is perhaps best summed-up by the words of its own author, Peter Flannery, preserved in one of the oldest documents the BBC holds on the series; from the early stages of its development at BBC Birmingham in June 1988.

“It’s a partial (incomplete, biased) account of growing up/growing old in the 60s and 70s. It lives and dies finally not on the strength of its political analysis, and certainly not on any kind of nostalgia for the era, but on the strength of its characters and its narrative. It’s meant to teem with life like the best of Dickens, and to capture the imagination and move the heart and mind like he does too.”

Paul Hayes is a writer and radio producer

Links

- BBC Four RemembersChristopher Eccleston remembers Our Friends in the North.

- Our Friends in the NorthPlaywright and screenwriter Peter Flannery has rewritten his multi-award winning and highly acclaimed TV series Our Friends in the North as audio drama for BBC Radio 4.

- BBC News - Culture TV classic's radio revival to reveal what Our Friends in the North did next.