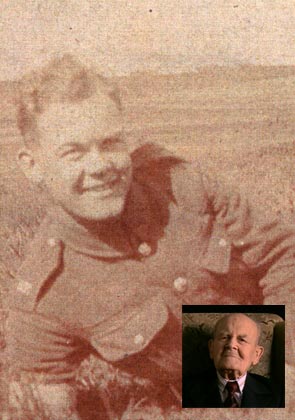

Arthur Halestrap: Walked the deck of the Titanic and survived Spanish flu

Born 8 September 1898, died September 2004

Before the war

I remember the ceremonies connected with Queen Victoria’s death … and I also remember very well the celebrations at the coronation of King Edward VII. And in Southampton, I remember the horse trams, and then there were electric trams.

We became very patriotic and at school we were taught a song, ‘Flag of Britain proudly waving over many distant seas, flag of Britain boldly braving distant fog and constant breeze, now we salute it and we pray God to bless our land today.’ That was the sort of song we were taught to sing at school.

Aboard the Titanic

I did go on the Titanic before she sailed. My next door neighbour was one of the engineers who developed the engines of the Titanic and on the first voyage … he was given a sort of honorary position as third engineer. Of course, he was drowned. When the Titanic disaster became known in Southampton, it was a terrible thing for the town because so many of the crew had their homes in Southampton. My mother knew many of the stewardesses. We were all mourning together at the same time. It was a terrible blow.

Volunteering

In 1914, I was 16 years of age and secretary of a bible class. The first lecture I gave after the outbreak of war, I criticised the Church of England for not protesting that two Christian nations were fighting one another. That is my first recollection of the war. Although I had volunteered at the age of 16 for the army but my parents had refused me permission to go.

Casualty lists

At the beginning of the war, the casualty lists were published in the daily newspapers, which … after a very short time was found to be very, very bad for morale. This was because ever so many volunteer regiments belonging to one particular village or town were very, very badly shelled and so many of them were killed. A whole town perhaps would have half its members killed in the war. Eventually, they said, ‘We will not publish the casualty list and when we send reinforcements to regiments, it will be people from all over the country.’

Long after the war, we were all together again and my sisters had married. The greatest boyfriend of one of my sisters who we couldn’t trace at all and we thought had been killed, came to see my father to ask if they could marry. In truth, he had been made a prisoner-of-war, and when he was released he came back to us and wanted to marry her. Of course, my father told him that she was already married and that it would be best not to contact her. And he agreed not to contact her, which was very fine of him I think. I think he went to Australia eventually.

Under fire

We’d been marching in the dark, of course. We had to because that terrain was very open and we had to do everything in the dark, at night, and we were marching up there and suddenly a Verey light [a type of flare] exploded. It has a very, very eerie sort of light. Then another Verey light exploded and then another, and then the shells started dropping and of course the horses started panicking. Horses were screaming all the time. Strangely enough, I was interested but not frightened because this was my first experience of shellfire. There was corpses all over the place. I remember that very, very clearly. That was my first experience of shell fire.

Shell shock

The discipline was so strict. I had to do what I was told. That is why I believe that discipline was the reason why we were so successful, because everyone felt like that. Not everybody though. One signals chap had shell shock and he was useless on the floor of the trench. We had the order to go over the top and the corporal looked at me and said, ‘Well, we can’t do much about him so we’d better get on with the job.’

We had to erect our wireless station and we did that despite the barrage that was coming over. Then the barrage lifted, but shells were still coming over. Afterwards, we went to get the shell shocked comrade chap and we helped him through and he recovered. He didn’t remember a thing about it, and we never mentioned it to him and the corporal didn’t mention it to anyone. I much admired that corporal because he could have reported him and he didn’t.

It was possible for those people to be shot by an officer for cowardice because they’d dropped their rifles and were what was called ‘cowards’. That was very debatable. I didn’t agree with it anyway.

Infected with lice

I asked my corporal after I went up to the trenches about how do I get rid of these lice? He said I should get a lighted candle and run the candle up the seams. Of course, the seams came apart because the candle burned the stitches. So I wrote home to mother and said, ‘I’ve got these body lice, what can I do?’ She wrote back and said, ‘You silly boy, you’ve got some Lifebuoy soap, use that. I’ll send you some more, rub the Lifebuoy soap up the seams of your clothing.’ Lifebuoy soap in those days was very strong disinfectant soap and I got rid of the lice that way.

Working in signals

We [the signallers] weren’t in the trenches all that time but we did go up to the trenches in support of operations and if the telegraph lines were down. When the lines were in use, we weren’t required. We had to find a place to erect our aerials and our station. We did it in holes in the ground, because the infantry said that we drew the enemy gunfire. So we had to find a place where we could hide ourselves and our equipment [masts]. When the masts were seen, of course, it would draw the shell fire, so we had to get out of the way of the infantry and away from the trench. We had to go onto the open ground where we could be spotted by the enemy planes when they came over.

Life in the trenches

I was walking in the trench which was so narrow. There was some barrage coming over so I daren’t show my head above. I had to walk on dead bodies. All I could say was to the chap who was dead was, ‘Sorry chum,’ and I didn’t think anything about it. He was dead and happier than I was. So I used to walk on the dead men and just apologise to them, and I felt like that.

Fear

The only fear I’ve ever experienced is when I was in the Second World War. I remember on one occasion I was in London for a week. I was in bed at night and I listened to the planes coming over and the bombs dropping all around me. In the morning at 5am, I came across a young girl and I said,‘Where you are going at this time of day?’ All around, there was water pipes, hoses, broken bricks and glass and all sorts of things. She said, ‘Oh I’ve been driving an ambulance all night,’ and she was quite calm. I’d been in bed all night absolutely shivering with fright at all these bombs coming down.

A close shave

There was a brewery in which we’d found a suitable spot to set up a radio station, just under the window. The floor was about five feet below the window, but we had to barricade those windows, so we spent a long time filling sand bags and building a huge barrier outside the window. It’s just as well we did. I know that we were sitting in the radio station, when all of a sudden there was a huge burst of sand bags through the window and we were buried underneath a mountain of sand bags and earth. The shell had a direct hit on our window.

A conscientious objector

On my first leave, [a friend had] been arrested as a conchie [conscientious objector] and sentenced to work on the land. He was working on the south coast somewhere near Brighton and I went to stay with him for a few days, and I found their conditions were worse than we were used to in the army. They were housed in just a wooden building with tiers of bunks and hardly any bedding. I stayed with him all the time and lived with him. They were just ordinary people, nice people. I think they were genuine. I know my friend was very genuine.

He had his views and I had mine… I didn’t believe in interfering with anyone else’s views, because I sympathised with them. I didn’t believe in war. War is a terrible thing. Even now, when I go out to speak, often the first thing I might say, is tell people that I don’t believe in war.

In the barrage

As the infantry advanced, the German gunners would alter their range to prevent supplies getting up to the front. Since we were always behind the infantry, we would sometimes be some way behind the infantry - until we caught up with them again - and then we would find ourselves in the barrage.

The barrage was something indescribable. It was all the small arms that you could think of, and the shells were also coming over. The shells were not only dropping in our area, but they were for different districts. The larger guns were sending shells to prevent supplies getting in.

Going ‘over the top’

I remember the infantry sergeant coming round with rum and giving it to each man before the over the top order was given. But he wouldn’t give the three of us any rum because we didn’t belong to him for rations. And so we had to go without our rum. But that was not long before the order to go over the top was given.

The Armistice

I took the signal for the Armistice, yes. And, from that moment the silence was - I can only describe it as terrible. It was. We seemed to have everything, well, as far as I was concerned - everything dropped away from me. I thought, ‘Now what will I do now, there’s no objective, there’s nothing in front of us. I’ve just got to wait.’ There was an absolute silence. It was indescribable really.

When you have, everything you’d been working for, for years, several years, suddenly disappear. No future. What is my future? What am I going to do next? Just wait for orders. And I had to wait for orders. I felt a sort of helplessness. What future? What do we do next? What do we do next? We had to wait to see what we’re going to do next.

Spanish flu

I became ill. And my corporal was very worried and he called the infantry corporal and the corporal called the sergeant. And he was worried and the sergeant called a sergeant major. And the sergeant major called the major and the major said, ‘Oh, I don’t know where the nearest medical unit is and if I did, it wouldn’t be in time. Fill him up with rum and let him take his chance. He’s got Spanish flu.’

The flu was killing millions in the world at that time. So I remember being hoisted up on my seat. I’m sitting on the floor on a blanket, that was all. And I remember taking rum and that’s all I remember. And the next thing I remember was when I said to my corporal, ‘Could I have a cup of tea?’ and he said, ’My God, we thought you were dead. You’ve been completely away from us for three whole days.’ Just like that. And from that moment I was better. I can’t bear the smell of rum now and I wonder whether that has kept me alive for so long now.

Serving in World War Two

I was in SOE [Special Operations Executive] then. I was chief signalmaster. I trained people of every nationality in Europe and across the world. And I made plans for them, signal plans and that sort of thing. But I haven’t mentioned World War Two yet. That’s a different matter. I should keep quiet about that. I understand that I’ve still got to keep quiet despite the fifty-year rule.