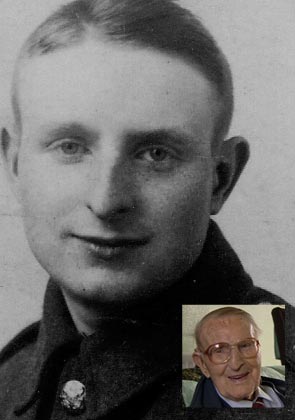

Arthur Barraclough: Went 'over the top' six times on the Western Front

Born 4 January 1898, died August 2004

Joining up

Any young man who was going to join the army went to the local Register Office and registered the name and so on and then you could go back home and do your job. And when your age were called, you’d have no fuss, you’d be drafted straight into the army. And so we went and registered and then we went to a career meeting – a big training camp and it was … a real big camp and this is where you learnt your soldiering.

Training

Every morning when you woke up, you had to make everything. When the officer used to come round, every bed had to be in a dead line. Every pillow had to be in a dead line. And when all the officers used to come round, slowly looking and if you put aught wrong you were for it. That meant you had to parade at night after you’d finished your daily parade - onto this night shift as you might say. And old sergeant major used to run you all up and down the parade ground at night. Our sergeant major was a proper villain. All the lads said if that fellah ever gets to France, he’ll never come out again.

Gas drill

You went to gas chambers where you got the old gas masks. In them days, it were a bag which you pulled over your head and tied in a knot under your chin. It had just one little tube for your mouth to breathe out of. But you couldn’t breathe in. You had to go through this gas chamber to see if everything were all right. It were a terrible thing, because each mask was soaked in some sticky black stuff so the gas couldn’t get to your face. And you couldn’t breathe through this little tube. All you could do was blow out.

Life in the trenches

Our cans were petrol tins that had never been washed out. So when our water ration was poured out into little cups, it tasted more like petrol than it did of water. It were absolutely awful. And of course we got a tin of bully [beef] to share for four men. And these tins of bully had a little key at the bottom but that key were always missing. So you had to chop it open with a bayonet. Because that little key had been pinched, or lost, or something. And so we had to drive it home with the point of a bayonet and try and lift the lids up, you know, to get at the bully. And it were a terrible job. We lost as much meat as what we got.

In Ypres, the Jerries had been before us and dug some dugouts, which were just right for a start. They were right if a Jerry barrage set up, to get down out for a minute, or getting a bit of a snoozer – useful. Anyway, in this dugout, somebody put some nails up at the top into the roof, into the wood of course. We’d heard that these dugouts were full of rats, so we hung up our haversacks on the nails with our rations inside. They were so many dog biscuits, a tin of bully and something else. Anyway there were three things in this safety bag, which was hung up for safety. But next morning, when we got up, well there were no sign. The bags had been pulled down and chewed up to nothing.

You just go down to sleep for a minute and you feel these rats running up and down you. It were awful. But you got that used to it when you were that tired, you ignore them. I’ll never forget that place.

Under fire

We got fed up of going down into the dugouts so we just dug a little hole in the side where you could just sit in. It was for the shrapnel and stuff. You could just be covered by it. Although, they were no good for a shell, but they were all right for shrapnel because it covered you. We just dug them into the side of trench and sat there, sat there when we had to be, if shrapnel come flying up, or if a plane tried to knock your head off. That high above the trench. Firing all the time.

Sometimes, I don’t ever remember seeing aught, but you could hear them coming you know, these plane bombs. And then these planes were flying out, they’d find something and report it to these reporters in the balloon and they’d report it to HQ or whatever and they pick spots out to fire behind our line.

Tanks

Big day come when the tanks come howling up. We all get set up behind our tank, two rows of men. When the tanks had broke down the barbed wire, the platoon were to open out like a fan and attack. But the trouble was that there’d been a lot of rain. And it were very sludgy and the tanks got stuck in the mud. So, this is right on paper, it’s all right for them. These two lines then had to open out and then push through the German lines to the victory.

Going ‘over the top’

I always said a prayer before going over the top. Six times - on six occasions on some bigger attacks and smaller attacks for some reason or other. I always used to stand when we’re all lined up with us rifles and bayonet all fixed for going over with, over with the lads. Our heart would be cursing and there would be all sorts of stuff going up in fright.

But I always used to just stand still for a minute and just say this little prayer. I’ll never forget it. ‘Dear God, I am going into grave danger. Please help me to act like a man and come back safe.’ And that’s what I did. And I went over without fear. That little prayer seemed to save my life because I had no fear left, although there were shells and bullets and all the rest flying when we went over and I were never frightened of being hit. It’s real funny that that prayer put me where I am now. In this chair. And that’s true. And six times I went up and six times I said that little prayer and each time I went up and come back safe. And I thank God for it every time.

A close shave

The officer in charge said to our, lance corporal, ‘Now look, you take your [Lewis machine gun] section and go to some old house and then fire across the enemy line and let us move on.’ There were four of us - the lance corporal to fire the gun, me to load it and two lads to fill the magazines. He kept on firing on and the lads kept on filling the magazines up.

Anyway, this went on for a bit and we did steady up a bit on the Front, till at last the Germans must have realised what were happening and sort of turned some of the guns onto us. These nine-inch shells came flying past us. They were getting down and lower down till they dropped one shell, hit the floor and burst right in the middle of four of us. The gun went west. The two lads that were just close up behind us, who were filling the gun’s magazine, were blown to smithereens. And me and the lance corporal were still laid down there. We were luckiest people on earth. We made our way slowly back to our home line.

Bearing bad news

I were in hospital with - I’ve forgotten which wound it was - and the officer came round and asked me if I knew any of these names. He read the names out. All them who’d been killed and, if they didn’t know, they were down as missing. And two of these lads’ names were on the list. I could only remember one lad’s name.

The officer said to me, ‘When you go home on leave, would you like to go to this young man’s family and tell them that he won’t be coming home, because he wasn’t a prisoner.’ And anyway, I went, I found the family and explained to them that he wouldn’t be coming back and that he wasn’t a prisoner-of-war or aught like that. They were very sorry and all that, but they couldn’t do nowt about it.

Gas attack

This were the time when they told us, ‘It’s gas, get your masks on!’ Well, there was such a big fuss and stuff, finding this thing to put over your head and then fastening it under your chin, and then finding the tube to breathe out of. And you couldn’t breathe in through it and so you just got to be strangled. You had to be fighting for breath coming through your gas mask. Some of the lads simply got fed up and couldn’t stand it no longer. So they just pulled them out and threw them away. They said, ‘Sod it, I rather be gassed, than try and breathe under these things’.

Barbed wire

All the barbed wire - that were the worst thing of the lot. ’Cos if you got tangled up in that, you were sitting room for all the snipers of the Jerry side, you see. It were that terrible stuff that it clung on to you as if it were alive. And you had a terrible job getting yourself free. And I always had that fear, so I was always terribly careful when I was anywhere near that barbed wire.

And there were shell holes all over on a lot of occasions, full of water, and this officer brought this ball of white tape and we just threaded it … and then follow this round … at that time No Man’s Land were full of shell holes, you know with shells going and bursting. And if it were raining they were full of water and it were a terrible danger … once you got in there, with it being sludgy, you’d have a hell of a time getting out of it.

Deadly legacy

After war had finished, we were collecting old rifles and all war stuff. We were set off going across fields, picking up rifles and bombs and anything else to do with war. And two of our lads come across some shells that had had been primed but never fired. And they got all these shells and picked them up. They were coming to the dump, when one of them shells slipped off his arm and hit the striking pin, and the shell exploded. They were both killed. It were terrible, after the war had finished. It were disastrous for they were just doing a duty of cleaning the countryside for the French folk.