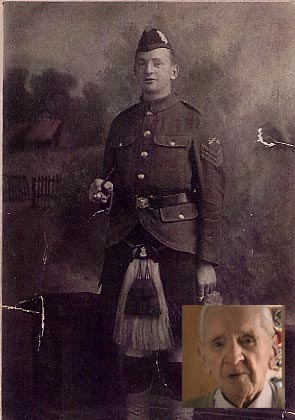

Alfred Anderson: Last of the 'Old Contemptibles', Britain's army of 1914

Born 25 June 1896, died 20 November 2005

Joining up

You were due a week’s holiday in summer but, being my father’s son, it was very seldom I got it. There was always some job going on I had to stay at home for. So, in the Territorial army, if you joined that you had to get a week off to go to camp. And that was the reason behind me joining the service. Most of the men were buddies, went to the same school, some in the same class.

It was only the following day and we [Alfred’s TA unit] were marshalled into the hall and asked what role there is for active service. That’s when it came home to us. We were committing ourselves. And who do you think was the first volunteer? Because my name was read out first. So I just volunteered. But I didn’t know it was for five years of war.

It was after [Alfred’s mother] knew that we’d volunteered for active service. She must have bought this bible, testament, specially for me. And written in it and then I went out in a lorry, an open lorry. I have the bible yet.

Arrival in France

It was quiet when we entered the village but the noises had gone up and the people were all rushing out their houses. And the majority of them was women. And they came and were shouting and screaming and all the like of that of course the kilt. I must say before I go any further that a Black Watch band was leading the battalion. It must have looked a very good appearance. However, they came rushing out of course and they weren’t too particular about clambering on the back and peeping up your kilt.

Infected with lice

At nightfall we were marched to these billets and there was straw laid all over - it was a byre. But it was all nice and dry straw as we thought. So we’re off with our everything and just laid there - we were dead tired. And I can remember waking up in the early hours of the morning, scratching yourself, looking round about. There was one single lantern above and you could see everybody - oh they were just moving [with lice].

The British Army has a cure for everything. Down the road a bit there was a fruit farm and it had two great big circular vats. Och, they would be about seventy, seventy-five feet wide, you know, and they filled these up with water and disinfectant and we were ordered to go down there, strip to the bare and delouse ourselves. That’s what we did. Had to jump in, everybody naked..... But it wasn’t a complete success because they were more in your clothing on the ground. So there was a guy there picking over that. Poor wee soldier.

Approaching the Front

See all these years I’ve been trying to forget. It’s all being raked up again. I think I was going to die peaceful like…

There was always a guide of Pioneers to take you into the section, take you there and show you. If they wanted a trench dug, you were to dig it. They marked it out on the ground. And that was generally at night … there was bullets flying overhead. When you hear it going ‘spt, spt, spt’ you know it’s fast.

If you was to be relieved it had to come in the dark. And you went out in the dark. It was the same with casualties. If there was a casualty in the morning you were there until dark. That was one of the bad things about trench warfare.

Life at the Front

You see, when you’re in the trenches ... you dug out your sleeping accommodation and you had one shelf about knee level, the full length of yourself, and then you got out the walls at the back and that was of another height, and that was accommodation for sleeping. And if it happened to be a period of rain, you put your oilskin sheet over the top and anchored it down. That kept you dry above.

Well the kilt was a bad thing. You were never dry. Dragged in the mud and water and that. The water came up your leg and it never really evaporated. Wherever you walked in the trenches, there were fellers who wore trousers if they wanted. And funny enough, nobody queried it. Because they were all glad to get out of the kilt themselves.

I never used to drink the water. Used to fill my mouth and wiggle my mouth about a way and just wash my mouth. Never used to swallow. Not until morning when you drank - a cup of tea brewing, maybe.

The ‘Christmas truce’ of 1914

We were not … in the first line, but we heard the complete silence and we stood in the road outside and listened. There was not a sound to be heard for a while, nothing. And then we heard some cheering. This had been the two sides fraternising, I think. Some of the boys came back from the front line and told us in the billets what was happening.

That was all the news that we had. But there wasn’t actually shell fire for a time, you know. Several were firing shots, then it became the usual thing.

Serving as a ‘batman’

Any message that had to be taken, the boy [Alfred, as an officer’s ‘batman’ or servant] was there, had to be there, to carry the message. Now you’ll say what use was the telephone in the trenches? Why, because they were all land lines on the ground and the rats ate the insulation, so making them useless.

Attacks and patrols

No, I couldn’t [say what it was like to go ‘over the top’]. Because the trenches that we were attacking were mostly blown away. There were shell bursts and they could fire accurately with these shells, I’m telling you … I think we ought to have had more machine guns. We only had one or two in each battalion. And the Jerries had one for every section.

Two or three men were ordered out into an empty shell hole or somewhere like that to listen and find out if there was any movement going on with the enemy. Any rumbling or noises like that with bringing up heavy material. So you were supposed to go out there in darkness and come back before daylight.

Getting wounded

We had been out all night. We came back to the platoon before daylight. And when daylight came we started to brew up. A shell came over and burst overhead. The first thing I can remember is being flat out. Some other lads had been in an open trench. Two or three of them killed outright. I was hit in the back of the neck. Where it’s still sore now.

At the first aid post there was a mule wagon with some wagons behind it. And there was room for me in the back of the last one. Believe me, it was an ordeal. Because the roads were no good. They were all shell-holed.

Condolences to the bereaved

Just shortly after I was wounded, my friend Lyon was killed. So first day when I went home on leave, I went round to Lyon’s house where he had three sisters. I said that I had come to pass my condolences to the whole family, but they refused to let me in. I asked why and one of the sisters replied that it was because, ‘You’re here and he’s no.’ I said, ‘Well if that’s your attitude, I don’t want to be in.’ So, that was it. I turned about and walked away.

He followed me as a batman [to the same officer]. They thought it should have been him standing there rather than me. We were always together. That hurt May [his sister] too. She was just thinking about me.