Agricultural Improvement Agricultural Improvement

One of the areas where the zeal for improvement manifested itself was in farming. The old ‘touns and clachans’ of Scotland, which worked the land communally, were ingenious adaptations to Scotland’s natural farming conditions; they were also relatively profitable, but the fundamental system of farming had changed little since the Middle Ages. Crops were grown in the runrig system: elongated s-shaped plots that were divided between the local community around the farm settlement in an intensively cultivated area known as the infield. Beyond this area was the less-intensively cultivated outfield, where livestock could be grazed on pastures. They were effectively islands of cultivation, surrounded by more infertile areas that were never tilled.

The onset of the Enlightenment brought dramatic changes in land management. Landlords introduced ‘improving’ leases to larger, single-tenant farmers in return for cash rents. The old system was swept away as fields enclosed by windbreaking hedgerows and trees were introduced. New principles of farming developed as the latest scientific knowledge was applied. Crop rotation rejuvenated the soil, and larger expanses of land were brought into production through the drainage of marshes and clearing of peat bogs. The profitability and productivity of the land soared, but within the actual farming communities (basically the majority of the population) there was greater stratification. For those who succeeded, the rewards were great, but many failed to meet their landlords' demands and the landless Cottar class was slowly squeezed out of existence. Agricultural improvement had an enormous social impact. In 18th century Scotland, the Lowlanders were the first to experience the agricultural revolution, and those who lost out were forced to move to the ever- expanding towns and cities, or sought new lives in America. expanding towns and cities, or sought new lives in America. The Highland Clearances

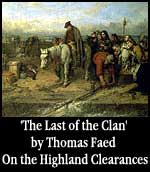

In the Highlands the impact of improvement came later and more rapidity. After the 1745 Jacobite Rising the clan system had been dismantled and the Highlands were increasingly commercialised. By the early 19th century, landlords found that sheep were more profitable than people. In the first phase of the Clearances the estates forcibly cleared the communities off the land to make way for sheep. Many people were moved into small single-tenant crofts, often on the most unproductive land, ensuring that they had to work part-time for their landlord in kelping or fishing to survive. The second phase of the Clearances came in the 1840’s after the collapse of the kelp industry and the onset of the Potato Famine. A ‘redundant’ population was forced by their landlords to either emigrate to North America, Australia or New Zealand or leave for the industrial cites of the Lowlands. Their were many winners in the Industrial Revolution, but many more losers.

| |  |  The BBC is not responsible for the content of external Web sites. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external Web sites. |

|