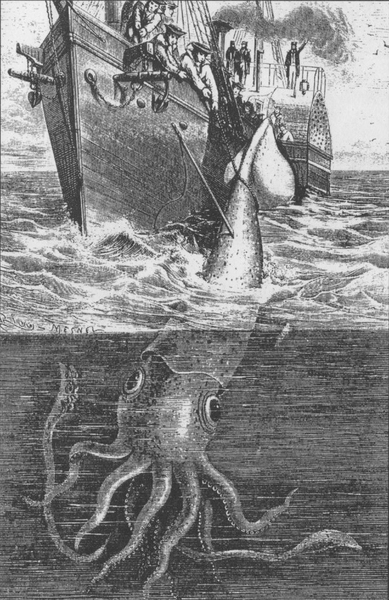

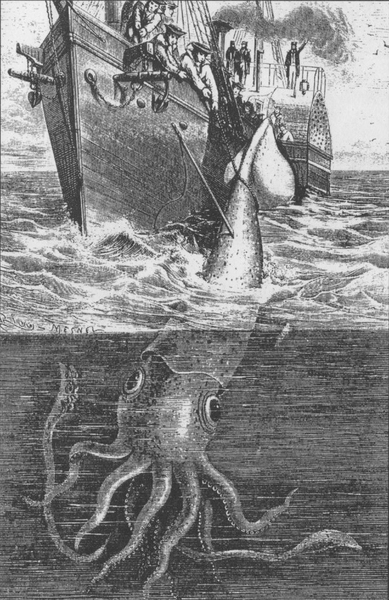

Illustration from the original edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea depicting a giant squid

Can a 13-metre long beastie, all tentacles and suckers, be a conservation icon for our time?

Scientists are proposing that the giant squid Architeuthis be emblemised and celebrated to help promote the conservation of marine diversity.

The giant squid would become the giant panda of the seas; a single species that captures the imagination, and stands for the world in which it lives.

It would become a rallying point for those seeking to protect life under the waves, the fish and the whales, the corals and crustaceans, an abundance of marine invertebrates and creatures we perhaps have yet to discover.

It could even become a marketing tool, a brand, a philosophy.

Rather than have to make complex arguments about marine food webs, carrying capacities, life histories and bycatch, people could support the saving of the seas by wearing a giant squid badge, while giant inflatable squids could be blown up at events designed to raise marine conservation funds. Anyone fancy running a marathon in a squid costume trailing eight arms and two 10-metre long tentacles?

It’s a far less ridiculous idea than it sounds.

Many people are already attuned to the fate of marine mammals, galvanised by the whaling debate, whale song soundtracks and the actions of organisations such as Greenpeace. The overfishing crisis gets good air time, and the epic journeys made by sea turtles prick something in the public consciousness.

However, most people aren’t aware that about 92% of marine species are invertebrates – animals that lack backbones. And though estimates vary a lot, there may be anywhere between 178,000 and 10 million such species living beneath the waves.

Even if people are aware these species exist, animals with exoskeletons or shells, such as corals, crabs and clams, tend not to tug at the heart strings.

Not like the giant panda, which has become the conservation icon for land animals.

The emblem of conservation charity WWF, by the charity’s own admission the panda is recognised worldwide as a symbol of conservation and sustainable development, and is perhaps better known than the work of the organisation itself.

Natural history author Henry Nicholls, who has written extensively about the giant panda’s allure, has recently published a comment piece in the journal Nature highlighting how different conservation organisations have embraced animal emblems.

His piece talks of how the marketing of these emblems has evolved over time, but it’s instructive to read how.

To quote:

Logos began to portray species that did have a clear conservation message. The dodo, the icon of extinction, was a perfect image for the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, founded in 1963 to support Gerald Durrell's pioneering conservation-focused captive work at Jersey Zoo in the Channel Islands. There were also more upbeat emblems. The moving tale of Elsa the lioness (star of Joy Adamson's novel Born Free and its 1966 Hollywood adaptation and memorable soundtrack) made her an exemplary face of the Born Free Foundation, established in 1984 to campaign against zoos and promote conservation in the wild. The RSPB's success in recreating the habitat suitable for breeding avocets in Britain during the 1940s made this species an obvious choice as an emblem.

Hence why marine biologist Angel Guerra of the Institute for Marine Investigation in Vigo, Spain and colleagues now argue that the marine world needs its own emblem.

In the journal Biological Conservation, they lay their reasoning for why it should be the giant squid.

At first glance, this huge invertebrate seems an odd choice.

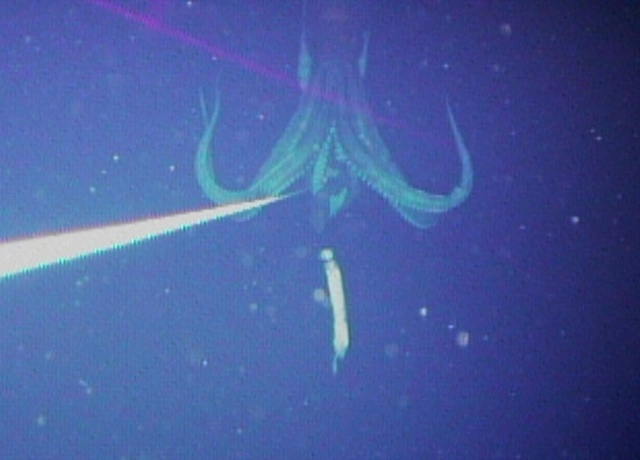

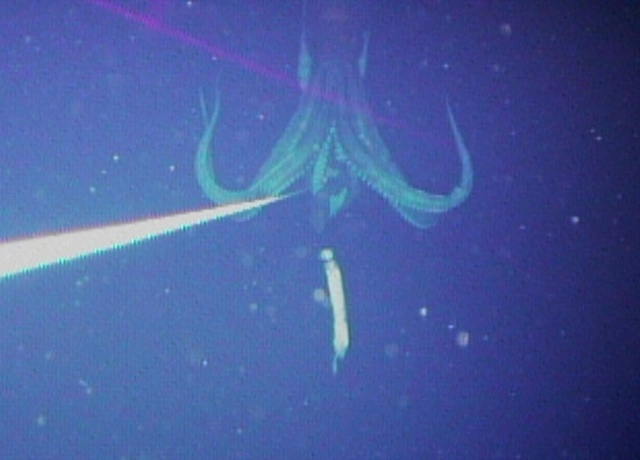

A rare glimpse of an adult Architeuthis dux in the wild (image: Dr Tsunemi Kubodera)

We know virtually nothing about it; the first pictures of a live, adult giant squid were only caught on camera in the wild in 2005.

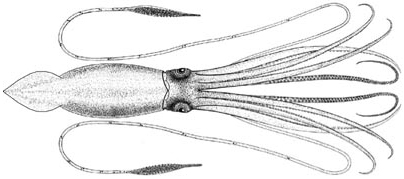

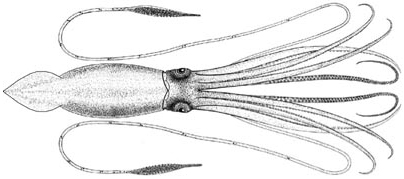

The 30 or so specimens landed to date reveal a huge animal up to 13 metres long with ten arms, two of which are massively elongated. The squid has a large beak which is uses to crush its prey. But we still know little about how it lives.

However, it does fit the requirements of an emblematic species, say Guerra’s team.

The animal that likely inspired the ancient mariners’ myth of the Kraken that appeared out of the deep ocean, the giant squid has long attracted the public’s attention.

It still has the power to awe: people flock to see the few specimens held in museums around the world, and giant squid get a significant amount of press coverage.

Architeuthis may also act as a bellwether for human impacts on the ocean.

As carbon dioxide levels increase in the atmosphere, more dissolves into the oceans, resulting in a fall in pH.

This increase in ocean acidity could make it harder for squid to produce small structures called statoliths which they need for movement and balance. That means more giant squid could float the surface, where they would die. More acidic oceans could also affect squid respiration and embryo development.

Giant squid modified from an illustration by A.E. Verrill, 1880

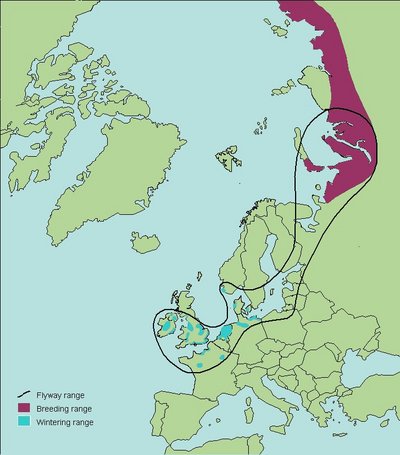

Although Architeuthis has been found worldwide (677 specimens recorded to date from the southwest Pacific to the northwest Atlantic), it mainly appears in areas with submarine channels or canyons that cut across the continental shelf.

These deep canyons are biodiversity hotpsots, and are vulnerable to deep sea fishing and dredging. Giant squid are also vulnerable to both, as well as pollution and potentially even seismic surveys or sonar.

The logic suggests therefore that if we learn to love, celebrate and protect the giant squid, we could also protect an entire unique marine ecosystem, and all the other more recognisable animals living within.

So is it a reasonable proposition?

Just a small population of reclusive giant pandas have enthralled us for decades now. Yet the species became the emblem of the conservation movement, not because it best represented the issues at stake, but because it was black and white.

As Henry Nicholls recounts in his Nature article:

“In 1961, as the WWF's founders mulled over the choice of their symbol in a plush town house in London's Belgravia, the most important consideration was that it should reproduce well on the organization's letterhead. With colour printing then out of the question for a fledgling charity, this narrowed the options to a shortlist of black-and-white species, and the popular panda emerged.”

So why not too the giant squid?

It isn’t as cuddly-looking as a giant panda.

But this outsized, almost monstrous sea creature of lore is perhaps the more enigmatic, secretive, bizarre and fascinating animal. It may also better represent the ecosystem in which it lives, and the threats to it.

Does it have what it takes for you to fall in love with it, and grant it emblematic status? Would you help save the giant squid, in a bid to save the seas?

I’m Matt Walker, editor of BBC Nature online. This blog is my take on the natural world, and how there’s more to Life than you may think.

I’m Matt Walker, editor of BBC Nature online. This blog is my take on the natural world, and how there’s more to Life than you may think.