The King of Storms: Supercells

It's twister season out in the US Midwest, with the long, straight roads of northern Texas, Oklahoma and surrounding states once again the annual hunting ground of hundreds of storm chasers and weather enthusiasts from around the globe.

Be they professional or amateur, they're all pursuing some truly awesome and rare thunderstorms of a very specific variety: Supercells.

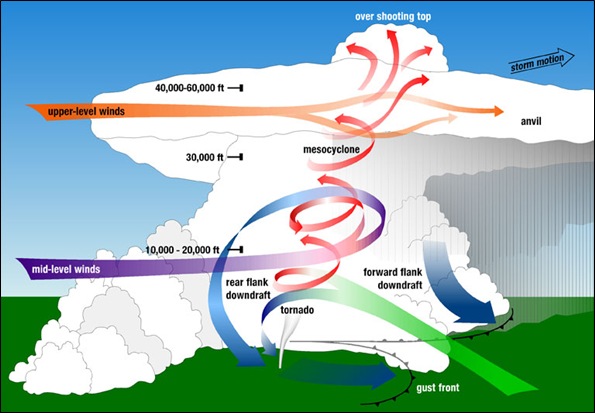

The colossus of the Cumulonimbus family, supercells are characterised by a persistently-rotating updraft (called a mesocyclone) that ensures the longevity of the storm cell; influences it's ground track and fuels it's propensity to deliver a variety of severe weather.

Sadly, the devastating nature of such extreme weather on lives, homes and businesses was exemplified over the weekend in Mississipi, as a supercell storm spawned a very powerful tornado - estimated at nearly a mile wide - which tracked across Choctaw, Yazoo and Holmes Counties, killing ten people, including three children. Elsewhere, further tornados struck across neighbouring Louisiana, Arkansas and Alabama.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

But what causes such violent storms - and are we at risk of them here in the British Isles?

Well, thunderstorms are commonplace worldwide, but severe ones - in the strict meteorological sense - are not. Approximately 2,000 thunderstorms are occuring around the world at any one time, with some 100,000 recorded globally every year. However, only 10% of these can be classified as severe. And of these, supercells are much rarer still.

To create any thunderstorm, some common factors must exist: deep instability in the atmosphere; moisture at low levels; plus a 'trigger' mechanism to force otherwise innocuous cumulus clouds to evolve skywards into giant storm cells. For example, this forcing might arise from the passage of a cold front; or when low-level winds converge and air is squeezed upwards; or from the lifting generated where air rises over high ground.

But for the atmosphere to cook-up supercell storms, a vital 'special' ingredient is also required: strong vertical wind shear.

Rather than replicate here some very good web examples illustrating this process, it's worth taking a peek at this website, which graphically shows how the critical influence of vertical shear can create a supercell storm, versus a 'normal' thunderstorm.

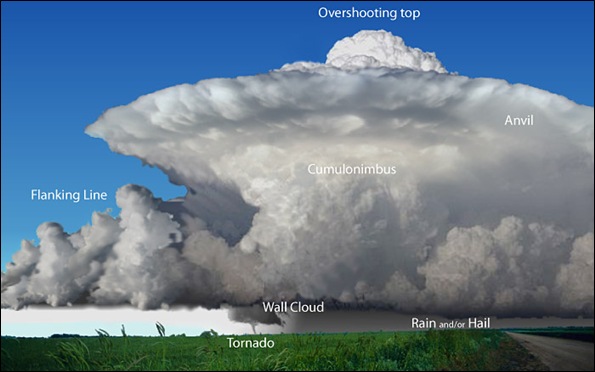

A colourful lexicon of meteorological and storm-chaser terminology has been developed to dissect this King of Storms into identifiable features. If you're after Overshooting Tops; Beaver's Tails, Wall Clouds or Flanking Lines, they're all here... See the graphics above and below, courtesy of the excellent website hosted by the US National Severe Storms Laboratory...

A colourful lexicon of meteorological and storm-chaser terminology has been developed to dissect this King of Storms into identifiable features. If you're after Overshooting Tops; Beaver's Tails, Wall Clouds or Flanking Lines, they're all here... See the graphics above and below, courtesy of the excellent website hosted by the US National Severe Storms Laboratory...

I've been under supercells in the USA and even for the most ardent storm aficionado, they can prove decidedly nerve-wracking experiences.

About ten years ago - on holiday just outside Nashville, Tennessee - I saw a tornado warning issued on local TV and I ventured out to video the weather, taking shelter under the eaves of a domestic garage.

The ink-black, turbulent cloudbase beneath a massive supercell delivered torrential rain; wild, gusty winds from the storm's outflow and frequent flashes of lightning. In the comparative clutter of this suburban environment - with many trees and houses blocking any clear, expansive view of the horizon - I appreciated just how difficult it would be to spot an approaching tornado in such circumstances during daylight, let alone after dark. It was frankly a claustrophobic experience.

The American system of tornado warnings has been developed over many decades, combining local doppler (NEXRAD) radars coupled to state-of-the-art meteorological analysis; a network of trained severe weather spotters across each state; an immediate media response to broadcast warnings and a generally high level of public safety awareness.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

A video of a tornadic supercell in Poland, August 2008. Three people were killed and several injured as severe storms lashed the country.

What about closer to home? Supercells occur across many parts of Europe and in 2008 and 2009, caused some deadly weather in parts of France, the Netherlands, Germany and Poland. They are also recorded in the British Isles, but are exceptionally rare here. Nonethless, it's worth noting that the unique dynamics of these storms - with their rotating updraft - were first described not in the USA, but in England, by noted meteorologists Keith Browning and Frank Ludlam. Their landmark study (available here in .pdf format) used radar to observe the characteristics of a spectacular hailstorm that tracked above Wokingham on 9 July 1959.

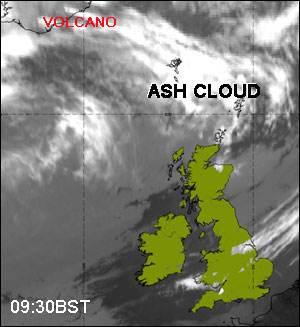

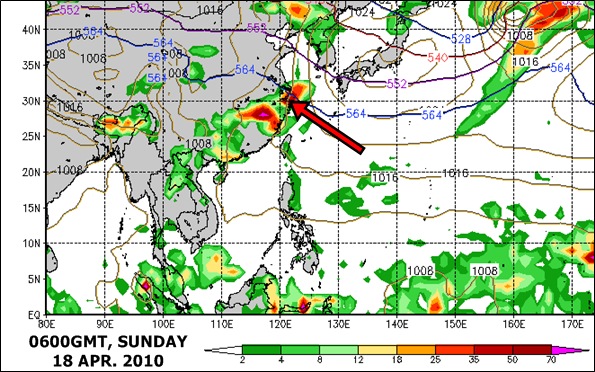

Last summer, I remember a couple of times - while on duty at the weatherdesk - watching supercells on radar and satellite forming in various parts of Europe, including just across the Channel over France and the Netherlands. I'm not aware of any that formed across the British Isles in 2009, but what will 2010 yield? We shall see...

Have you experienced any European or British supercells? Share your experiences on the blog and feel free to send me any photos (instructions are here) - I'll show the best ones below.

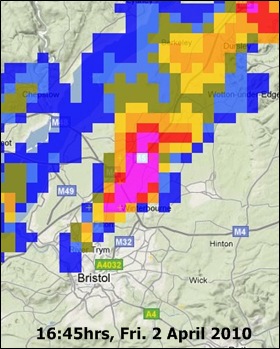

During my morning shift yesterday on tv and local radio, I'd been mentioning the strong likelihood of some areas across the West Country seeing thunderstorms with hail during the afternoon. As a storm aficionado, I was delighted to have the most intense one showing anywhere on the radar deliver the goods right above my home!

During my morning shift yesterday on tv and local radio, I'd been mentioning the strong likelihood of some areas across the West Country seeing thunderstorms with hail during the afternoon. As a storm aficionado, I was delighted to have the most intense one showing anywhere on the radar deliver the goods right above my home!

I'm Ian Fergusson, a BBC Weather Presenter based in the West Country. From benign anticyclones to raging supercell storms, my blog discusses all manner of weather-related issues. I also provide updated race weekend forecasts tied to our BBC coverage of Formula One. You can follow me on

I'm Ian Fergusson, a BBC Weather Presenter based in the West Country. From benign anticyclones to raging supercell storms, my blog discusses all manner of weather-related issues. I also provide updated race weekend forecasts tied to our BBC coverage of Formula One. You can follow me on