Meet the ancestors

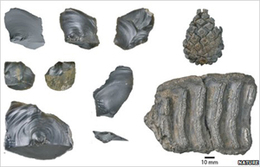

This unremarkable collection of shattered flints, fossilised plants and bone fragments may not look like much to you or me, but to the scientists who uncovered them on a beach in Norfolk it's a spectacular haul that suggests our earliest human ancestors may have arrived in Britain nearly a million years ago.

The discovery, published in the journal Nature, pushes back the arrival of our earliest human ancestors by more than 250,000 years, and throws up all sorts of interesting questions about who these people were, and how they lived.

Since the climate at that time was more like that of southern Scandinavia, it implies they may have been among the first humans to use fire to keep warm, and to wear skins and fur.

"These finds are by far the earliest known evidence of humans in Britain," according to the Natural History Museum's Professor Chris Stringer, a lead author on the paper.

"They have significant implications for our understanding of early human behaviour, as well as when and how our early forebears colonised Europe after their first departure from Africa".

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

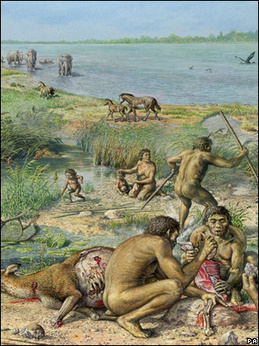

Happisburgh on the Norfolk coast is more famous today as the site of a village that is rapidly being washed away by the North Sea. But 950,000 years ago the area would have been joined to the continent by a land bridge. These early humans would have lived cheek-by-jowl with sabre-toothed cats, primitive horses, mammoths and giant hyenas on the forest fringed floodplain of the ancient river Thames.

Until recently our earliest human ancestors were thought to have been confined to an area of Europe south of the Pyrenees and Alps.

While that line ebbed and flowed as the climate changed and ice ages advanced and retreated, it was assumed the colonisation of northern Europe came much later, with the earliest evidence for the occupation of Britain dating from sites like Boxgrove in Sussex at 500,000 years ago.

While that line ebbed and flowed as the climate changed and ice ages advanced and retreated, it was assumed the colonisation of northern Europe came much later, with the earliest evidence for the occupation of Britain dating from sites like Boxgrove in Sussex at 500,000 years ago.

Then, in 2005, evidence from Pakefield in Suffolk pushed back the date for the human occupation of more northern latitudes to 700,000 years. The Happisburgh site extends the record even further, to somewhere between 800,000 and 1.2 million years.

"These new flint artefacts are incredibly important," says the British Museum's Dr Nick Ashton. "Not only are they much earlier than other finds, but they are associated with a unique array of environmental data that gives a clear picture of the vegetation and climate. This demonstrates early humans surviving in a climate cooler than that of the present day".

It's this climatic data - from the fossilised plants and pollen grains present in the deposits - that has lead scientists to speculate the happisburgh humans may have used fire, worn skins, and even constructed shelters to keep warm.

The winters in particular would have posed a severe challenge to anyone living in the open on this marshy floodplain.

Sadly, we know even less about the people who made the Happisburgh tools. Professor Chris Stringer believes it's possible they were related to the species Homo Antecessor, or pioneer man, found in deposits of similar antiquity in Spain.

But without the "holy grail" of fossilised human remains to study no one can say for sure.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

Comments Post your comment