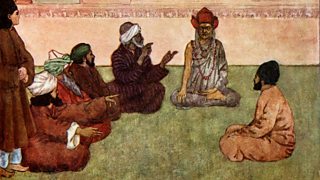

Editor's note: In Thursday's programme Melvyn Bragg and his guests discussed The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. As always the programme is available to listen to online or to download and keep

Hello

The rise and fall of reputations is fascinating. In Iran Khayyam was known as a scientist, particularly as someone who reinvented the solar calendar. His poetry is, as was made plain on the programme, something not mentioned in his own era (or was it mentioned once?) Anyway, he was not known as a poet. Now, as a result of Edward FitzGerald’s translation, he is acclaimed as a fine poet in Iran, although the very latest scholarship there suggests that there is still some academic uncertainty about his relationship with these quatrains. I think we didn’t make quite clear the immensity of the task that FitzGerald set himself. He set himself to learn Persian as an Iranian might set himself to learn English, but the Iranian would be setting himself the task of learning English to translate Chaucer, in the way that FitzGerald was learning Persian in order to translate a 12th century text. No wonder he went through medieval Latin first. Or, another way to put it is, what a wonder he went through medieval Latin first.

So, a fine May morning and off to vote. I nipped round when the doors opened at seven o’clock. I’m lucky in that the polling station near me is near the Heath and so it was a stroll through the fresh air and birdsong to Keats House. It felt very privileged to go in there, in this calm place, and take my one-fifty-millionth part in democracy. It’s quite a treat to vote when you’re in the Lords because, along with criminals, the lords are not allowed to vote in general elections, so putting crosses on pieces of paper took me back.

Last night I was at an event to commemorate Beryl Bainbridge. Her paintings have been given an exhibition space in King’s College. Some of them are quite wonderful. She was such a talented woman. The British Library has also released some first editions of her books, on several pages of which she did paintings. There’s also a replica of a corner of her extraordinary Victorian room, although you will all be grateful to know that the full-sized bison which dominated the hall in her house in Albert Street has been left in Albert Street.

The night before that I was at the British Museum for an exhibition of Egyptian mummies. Eight new mummies, one – the oldest in the world – which comes from 3500 BC. It’s a young man who had been buried in a shallow grave of sand, but the sand was so dry that there he is, crouched foetally, a perfectly presentable skeleton. But what the British Museum has done is to bring extraordinary X-ray techniques to bear on it, so that we not only see inside the mummy cases and through the bandaging but through the body itself, so we can see which organs were taken out; where, if taken out, they were displaced; and also the amulets that were put inside the opened-up body to charm them through to the next world. A small, perfectly formed exhibition which leaves you wanting to go round a second time, instead of, as often happens at exhibitions, wanting to find the nearest armchair.

All sorts of difficulties last week. Arsenal gives you a lot of grief. Why did they have to go 2-0 down in the first eight minutes last Saturday, when we had so carefully gathered round the television, expecting, if not a walkover, then at least a well-deserved (as we thought) victory? One of the problems was a tension between sympathy for the underdog (Hull City) and a deep wish that after nine years Arsenal would win a trophy. It was resolved with dignity all round – which I’m afraid includes the fact that Arsenal won.

And again there will be problems on Saturday when Saracens face Toulon. Saracens are an English-based team (to say English would be pushing it an awful lot) and Toulon is a French-based team, but Toulon is led by Jonny Wilkinson in the second last game of his career. So there’s sympathy there. On the other hand, Saracens is led by young Owen Farrell, Wilkinson’s natural successor …

Pleasure can be very strenuous some days. I think I’ll go back to the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and especially that stanza:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

Best wishes

Melvyn Bragg

Download this episode to keep from the In Our Time podcast page

Follow Radio 4 on Twitter and Facebook

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external websites