Editor's note: This week Melvyn Bragg refers to the two latest episodes of In Our Time about George Fox and the Quakers and Early Geology. As always the programmes are available to listen to online or to download and keep - PMcD

Hello,

Sorry I didn't manage a newsletter last week. This is a double issue. But it won't be twice as long - I promised Ingrid! Last week I hared off from the programme to Heathrow to jump in a plane to go to New York to interview Nick Hytner about One Man, Two Guvnors and its transfer to New York, and Baryshnikov about the male dancer, both for a new series of The South Bank Show we are about to do, and in the process I forgot the newsletter.

The next day was Good Friday when even Ingrid would not be in the office. Therefore pointless to do a newsletter. I wanted to talk about the Quakers I had known back in Wigton in the 1950s. There was a Quaker school on the edge of the town, said to be the first co-educational boarding school in the country. The Quakers came into the town itself to a fine, plain, brownstone meeting house which later became the town library, run by Quaker ladies who I remember as almost beatific in their kindness and assistance. I also remember helping them to put up the boards in front of the books so that the spines of the volumes did not interfere with the calmness of the Quaker meetings, and it was panelled all round the room.

I thought of the Quakers then as pacific, kindly and altogether exemplary in their quietism and even in their meetings (rather than services). It seemed to me (a few years later when I learned about the Celtic monks) to hark back to a purer and more inspirational notion of Christianity, which itself harks back to what we know of the Apostles through Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

We played them at rugby which was a bit unfair because we had a rather larger school than they had. And they have stayed with me as a presence. I wasn't surprised when Tom Morris, the producer of In Our Time, told me that there had been a far greater than usual response to this programme on the audience log etc, and also observed that a friend of his had said that the Quakers were the only people that every faction in Northern Ireland, at the worst times, felt they could talk to.

I like the idea of Pennsylvania. I like the idea of turning to chocolate in order to give people an alternative to drink. I also like the idea that perhaps they didn't understand that to have a glass of red wine AND dark chocolate is irresistible.

This week: geology, which takes me again back to Cumberland and to a man called Otley. He lived upstairs in one of the little half houses in Keswick and was a geologist of great note. He was part of that cluster of talent in the Lake District around and about the time of Wordsworth and Coleridge and Southey and Thomas de Quincey.

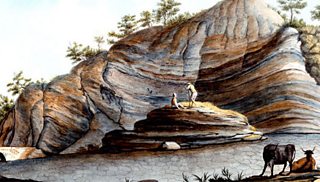

Once geology had got underway with the Germans discovering that when you went down deep you found a different view of the Earth than that thought of in the abstract by Aristotle, then the British Isles came into their own and undoubtedly, in the 19th and early 20th century, led the way. This is the most geologically varied area of land in the world, and mostly we celebrate that on the surface by appreciating different landscapes from the Highlands to the Chilterns, from Cornwall to the flatlands of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Also in Cumberland you had the great presence of John Ruskin - perhaps the greatest dominating intellectual of the second half of the 19th century in Western Europe - and he spoke of geology as hearing the clink-clink of the hammers of the geologists, which were chipping away and chipping away at his faith.

Best wishes

Melvyn Bragg