Coal takes the strain...again.

On BBC Look North on friday I reported that during the recent intense cold weather, it's been our traditional coal and gas fired power stations that have been working flat out to keep our homes and businesses warm.

And for the third winter running, the intense cold has gone hand in hand with periods of little or no wind. This should come as no surprise since prolonged cold is invariably associated with areas of high pressure.

Peak demand also comes during summer heat waves - as we all turn on our air conditioning units - again usually associated with areas of high pressure, with little or no wind.

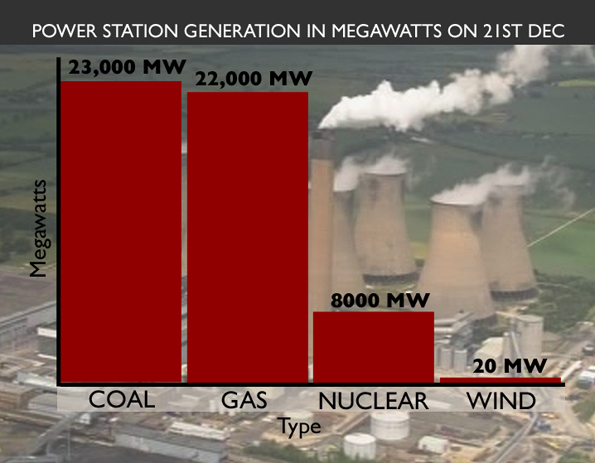

December 21st 2010 was one of the coldest days on record in Yorkshire. The bar chart below gives an idea of how much electricity was being generated by which type of power facility, when temperatures were at their lowest.

With much of the country experiencing very little wind, both onshore and offshore, wind turbines were largely inactive.

At the moment that is not a problem. Only 5% of electricity is currently generated by wind farms, and so other power stations can step in and ramp up output.

But in only 9 years time, the UK will legally have to generate around 30% of its electricity from renewable sources, of which 25% is expected to come from wind farms alone, as it is seen as a clean, carbon free energy source.

So what will happen then, when the wind doesn't blow?

If a similar meteorological situation occurred in 2020, then almost 25% of power would have to come from sources other than wind.

This means that there would have to be some power stations - using coal or gas, since nuclear power output can't be increased at short notice - that simply exist as a stand-by facility, in case the wind doesn't blow.

And that's a very expensive way of producing electricity.

And what happens if, as seems at least possible, the next 10-15 years sees an increase in the type of disrupted weather patterns that we have experienced recently, because of solar considerations?

Professor Mike Lockwood at Reading University thinks that the UK could indeed experience colder winters on average, compared with the last few decades because of the sun's low activity.

This would lead to a higher frequency of 'blocking' weather patterns leading to less frequent windy conditions than would normally be expected if one looks at climatological averages - suggesting we would have to continue to rely on coal and gas fired power generation well into the future - and possibly more than is currently envisaged.

Hello, I’m Paul Hudson, weather presenter and climate correspondent for BBC Look North in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. I've been interested in the weather and climate for as long as I can remember, and worked as a forecaster with the Met Office for more than ten years locally and at the international unit before joining the BBC in October 2007. Here I divide my time between forecasting and reporting on stories about climate change and its implications for people's everyday lives.

Hello, I’m Paul Hudson, weather presenter and climate correspondent for BBC Look North in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. I've been interested in the weather and climate for as long as I can remember, and worked as a forecaster with the Met Office for more than ten years locally and at the international unit before joining the BBC in October 2007. Here I divide my time between forecasting and reporting on stories about climate change and its implications for people's everyday lives.

Comments

Sign in or register to comment.