Science happens in funny places. In this case I was in the back of a truck as number-crunchers in Vienna piped back massive amounts of data to a field near Stonehenge. And what the archaeologists saw made them very excited.

Science happens in funny places. In this case I was in the back of a truck as number-crunchers in Vienna piped back massive amounts of data to a field near Stonehenge. And what the archaeologists saw made them very excited.

Stonehenge dominates the Wiltshire landscape. So it's not a complete surprise that everyone from tourists to archaeologists tends to focus on the huge stones themselves.

But I was there filming the work of an international team lead by the University of Birmingham who are turning their back on the ancient monument and facing outward. Examining the 14 sq km around Stonehenge itself. Believe it or not about 90% of this land is, in archaeological terms, a complete blank.

But that's changing as researchers carry out the biggest archaeological survey of its type in Europe. Not using shovels but instead scanners that can be dragged across the surface of the landscape. Geophysics has revolutionised modern archaeology and this kit is the very latest gear, fresh out of the lab. It can be attached to quad bikes, tractors and even 4x4's and gather data when driven at high speed.

This new technology means you can now cover a huge area in a short period of time and gather extremely detailed information. It wouldn't even be possible to carry this sort of survey with a trowel. No matter how many students you convinced to live in a tent for the summer.

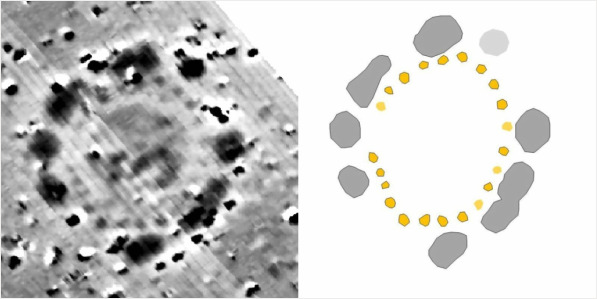

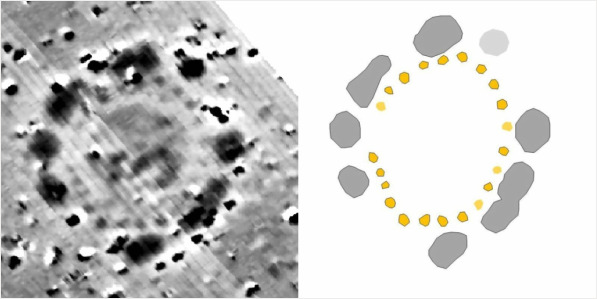

The team was very excited when I was there by this black and white image. It's a scan of an existing barrow and in this image the archaeological team see a segmented ditch and 24 deep pits which they say would probably have been dug for timbers and a wooden structure. A wooden henge. The diagram on the right shows this more clearly.

The team say this is the most exciting discovery at Stonehenge for 50 years. It means at its greatest the monument didn't stand alone in the landscape but instead there was another henge nearby looking down on it.

Interestingly this barrow has been investigated in the past. But in those days people just dug straight down looking for the burial chamber and any ancient gold. What this scan reveals is what's going on outside the previous limited archaeological investigations.

And of course that's true of this entire area that's been scanned. There's still much more data to be analysed. Who knows what the team will discover next? In the meantime the equipment is being packed up and is off to scan a series of archaeological sites across Europe.

UPDATE

For those that wanted more technical details about the work here you go. The team are using a variety of techniques including ground penetrating radar (GPR), magnetic surveys, resistivity and electromagnetic studies. Traditionally GPR and magnetic studies involve a single user pushing or pulling a single detector over the ground to take the data.

But the team have been able to scale up the size of the detector four or five times and increase the speed they travel over the ground up to 6mph which allows them to hook the detectors to tractors and similar. Obviously speed will affect resolution. But the team have managed to cover an area of fourteen square kilometres around Stonehenge in three weeks.

Since the equipment really is fresh out of the laboratory I don't have technical specs for all of it. But for the GPR detector we saw was operating at 250MHz which on this soil will penetrate to about 2m with a resolution of about 5cm.

UPDATE II

*ping!* An email arrives from Scott Palmer correcting our use of the word henge when referring to Stonehenge itself in this story. He explains that Stonehenge is so called because it looks like an old fashioned hangman's scaffold. Henge being a corruption of "hang". All other ceremonial monuments are called henges in tribute to Stonehenge. But it does mean that technically Stonehenge itself isn't actually a henge.

Those that want to save the planet make strenuous efforts to get us to use our cars less and take fewer foreign holidays. Which is odd as it looks like it's what you eat, not what you drive, that has the biggest impact on the environment.

Those that want to save the planet make strenuous efforts to get us to use our cars less and take fewer foreign holidays. Which is odd as it looks like it's what you eat, not what you drive, that has the biggest impact on the environment.

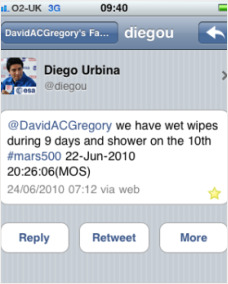

I'm David Gregory, BBC Science Correspondent for the West Midlands. My first law states: "Science is the answer." There is no second law. Feel free to drop me a line:

I'm David Gregory, BBC Science Correspondent for the West Midlands. My first law states: "Science is the answer." There is no second law. Feel free to drop me a line: