Straight talking from the top, at MoD Abbey Wood.

Why do military jets cost billions more than planned? Well, "it's a bit like buying a conservatory."

How many jobs are at risk at the MoD's centre at Abbey Wood, near Bristol?

"It could be as many as 2,000 jobs, yes. That is entirely within the realms of possibility."

Civil servants are normally cautious, tight-lipped people. Engineers, in my experience, rarely like sweeping statements. And military people are almost congenitally discreet.

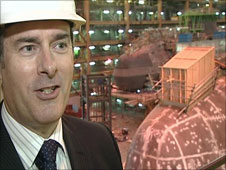

So when I arrived to interview Britain's senior military engineering civil servant, I didn't expect much.

But Dr Andrew Tyler is renowned for his plain speaking approach. The man who leads 21,000 people who buy all the kit for the armed forces had clearly had enough of softly softly. He was fed up of reading stories about dodgy radios and unprotected land rovers; 'our brave soldiers let down by the pen-pushers', as the papers put it.

"It is one of my biggest frustrations that we are a bunch of bureaucratic pen-pushers," he told me. "Nothing could be further from the truth."

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash Installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

We walked around the calm landscaped grounds of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) headquarters near Bristol, and he pointed to an office block. "Every office here is in constant contact with the front line," he insisted. "The teams are just a phone call away from Libya, an email from Afghanistan."

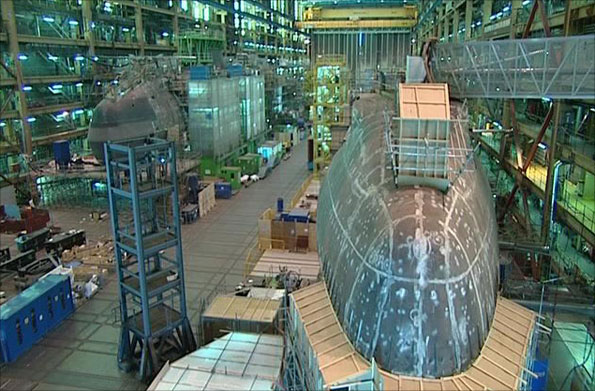

Inside Abbey Wood with the boss

But does that excuse multi-billion pound cost over-runs?

The RAF's new fast jet, the Typhoon, is £3.5 bn over budget. It's worth spelling that out: £3,500,000,000 more than was originally estimated. How does that happen?

The standard tactic for disarming this dangerous question is to bore you to death. Defence officials bombard you with details of multiple tenders, of specification shifts, of sophisticated technology prototypes.

Andrew Tyler talks about conservatories. "You sit down with your wife," he tells me, as if we were leaning on the bar, "You budget for eight or nine thousand pounds, and as sure as eggs is eggs, when the builder leaves the premises you've got a bill for fifteen."

It's refreshing. The problem is in the initial estimates, he explains. 'Natural human optimism' produces low figures when the aircraft carrier or submarine is being planned. And then, just like the builder in your back garden, everything goes up.

8,000 people work at MoD Abbey Wood

He was just as frank on jobs. When the defence secretary announced, back in October, that a quarter of all MoD jobs would go by 2015, we all did the maths. 8,000 people work at Abbey Wood, so that sounded like 2,000 job losses. But for months, the MoD has been silent on the detail.

Not Dr Tyler. 2,000 job losses is "entirely within the realms of possibility". Abbey Wood is on a quest for even greater efficiency, he explains, and "that is definitely going to require doing the same thing with less people. It could be as many as 2,000 people, yes."

Now this isn't a bolt from the blue. He is essentially confirming what we already knew. People won't be leaving overnight, the process will take three years. A voluntary redundancy scheme is already proving popular.

But what is really remarkable here is the candour. We have grown used to Whitehall code, where everything is carefully couched and you have to read between the lines. Andrew Tyler clearly thinks that culture has brought us billion pound overspends and nervous staff. It is now time, he is saying, to be honest about what submarines and fast jets will actually cost, and tell staff how many jobs will actually go.

There is a footnote to this story. One of those jobs that will go is the Chief Operating Officer. Yes, Dr Tyler himself has been restructured out of the MoD. By the end of the year, his post will be no more, and he will be back in the private commercial world. Inside the world of defence contracting, people will remember him for lots of technical and substantial changes.

Outside, we will remember a military engineer who decided it was time to rename 'personal operational excavation devices', and call a spade a spade.

Hello, I’m Dave Harvey – the BBC’s Business Correspondent in the West. If you’re making hay in the markets or combine harvesting; scratting cider apples or crunching tricky numbers – this is your blog too.

Hello, I’m Dave Harvey – the BBC’s Business Correspondent in the West. If you’re making hay in the markets or combine harvesting; scratting cider apples or crunching tricky numbers – this is your blog too.