Reporting the Hillsborough inquests: An unforgettable two-year assignment

Ben Schofield

BBC Radio Merseyside reporter

Ben Schofield (pictured reporting from outside Warrington coroner's court) has been the BBC’s dedicated reporter throughout the two years of the Hillsborough inquests, covering the historic hearings for local, regional and national audiences. Here he describes some of the unique challenges he faced as a journalist:

The second Hillsborough Inquests began almost 25 years after the disaster. They followed a public inquiry, criminal investigation, the first inquests, High Court challenges, a judicial scrutiny of the evidence, private prosecution and a 400-page report by the Hillsborough Independent Panel (HIP).

As such, reporting these new hearings was never going to be straight-forward.

The new coroner would sit with a jury; contempt of court rules would apply and the Attorney General warned the media to behave.

But even before a day of evidence, we knew a great deal about the events of 15 April 1989 and the aftermath.

In 2012 emergency service chiefs had issued full-throated apologies for their predecessors’ errors. South Yorkshire Police’s Chief Constable even said that the disaster and subsequent alleged ‘cover-up’ was “possibly the most shameful episode in British policing”.

Pictures of euphoria among the bereaved families – as the HIP report came out and the new inquests were ordered – were part of the audience’s recent memory.

Our legal advice, however, was to treat this case like any other major court case. Facts about the disaster and the years that followed were limited to what the jury was being told.

So what could we say about the previous inquests, which surely needed explaining as a part of any story?

It was fine to report that inquests were held in 1991, but their ‘accidental death’ verdicts were off limits.

Likewise, the Taylor public inquiry’s finding about police failures, including a “blunder of the first magnitude”; the conclusion of the private prosecution in 2000, when a jury could not decide on a manslaughter charge; and evidence from HIP of police attempts to deflect blame on to the fans, were all no-go areas.

After all, a jury was being asked to decide the ‘facts’ of the case afresh.

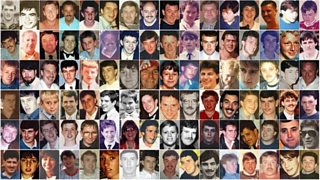

The 96 victims of the Hillsborough disaster, whose deaths have been ruled to be "unlawful"

A compilation of ‘approved footage’ of the disaster was cut down to the bare minimum, so we couldn’t inadvertently broadcast material before it was shown to jurors, or even pictures they were never going to see.

It was like the previous 25 years had never happened.

All this was done to avoid the ‘substantial risk of serious prejudice’ that all court reporters in England and Wales must beware.

But thankfully our coverage wasn’t limited to a dry reporting of court procedure.

Early on, a decision was taken that we could broadcast pre-recorded and legally cleared interviews with the bereaved families.

These were voices that our audiences – especially those of local radio and regional news – were used to hearing.

Should they be silenced for the duration of the two-year process?

Returning to the major trial comparison, it would be unthinkable to broadcast clips with, say, the mother of a murder victim on the eve of an alleged killer’s trial. But we felt we were able to do the equivalent.

So long as the families weren’t commenting on the evidence presented at court, they could speak about the emotional ups and downs of following the case.

It was, for us, an important part of the story, especially as the hearings took far longer and were a much greater ordeal for relatives than anyone could have anticipated.

It is highly unusual, in the days of rolling 24-hour news, to cover a single story for two years.

But by having a dedicated Hillsborough inquests reporter, not only were we able to serve audiences that wanted to follow the hearings’ every twist and turn, we were also able to keep BBC News as a whole updated with the progress of the hearings and what was going on behind the scenes.

Alongside filing for local radio, online and TV, I tried to build relationships with some of the key legal teams at court. They were invaluable in helping me predict what might happen in the coming weeks – crucial information in a long-running case.

Then there was how to keep track of the sensitive video being played in court.

Of course, we needed to know precisely what had been shown to the jury so we could broadcast it during our coverage.

Much of the material was too graphic to broadcast and could have upset the families had we shown it.

We were able to negotiate with the coroner and the families’ legal teams two protocols – each for different phases of evidence – that allowed the media to receive a massive archive of video footage in advance of it being played in court.

We agreed only to broadcast excerpts from that material which met two criteria: that they had been shown in court and that families hadn’t objected to their re-broadcast.

It put the onus on me to keep track of precise timecodes of footage and of the families’ wishes, but allowed us to have material ready to air shortly after the jury had seen it.

So much about Hillsborough is unprecedented: the UK’s biggest sports stadium disaster; allegations of a massive police cover-up (which continue to be denied); a justice campaign spanning three decades; and the longest inquests in British legal history.

I’ve only covered one chapter in a remarkable story. It has had practical, and emotional challenges.

Some of our approaches to the story have been as unique as Hillsborough itself, others may be replicated and inform our coverage elsewhere.

For me, the memories of the coroner’s court in Birchwood Park, Warrington, and of spending time with some remarkable families, will live with me throughout my career.

The reporting of Hillsborough: Unfinished business