What makes Great British weather?

Distance travelled ~ 499'123'200 km

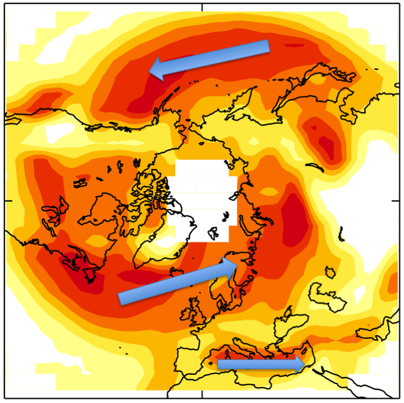

The weather of Great Britain is notoriously fickle. One day brings sunshine, the next is dull, while a third pours with rain. Britain froze under a blanket of snow for weeks in December, sweltered in a burst of heat in April and brought umbrellas out during an inclement early summer. But why is Britain's weather so variable? To understand that, we must first understand Britain's place in the world. Britain lies at the downstream end of the North Atlantic storm track, a feature that dominates the weather and climate of the North Atlantic and Western Europe. The phrase "storm track" is used to describe the typical paths of low-pressure weather systems as they move eastward in the jet-stream across the North Atlantic Ocean. Similar storm tracks can be found in both the North Pacific and the Southern Oceans.

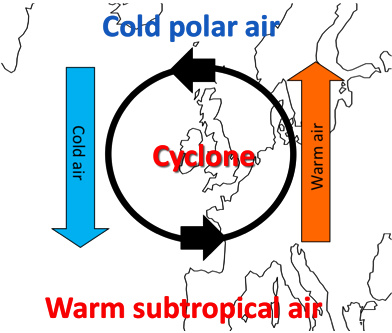

Each individual low-pressure weather systems is referred to as either a "cyclone" or a "storm" - the storm track contains many moderate systems as well as the really intense events that are more commonly called storms. Around each storm, the wind flows anti-clockwise along lines of constant atmospheric pressure. To the west of the storm the winds are from the north, bringing cold polar air southward, while to the east the winds is from the south, bringing warmer subtropical air. The join between the warm and cold air masses is known as a "front", like a battle-line between two opposing armies. As a storm moves eastward overhead, we first feel the effects of the warm front - the warm air moving north, raising the local temperature - followed by the cold front - the cold air moving south, lowering the temperature back down again.

Small droplets, however, do not necessarily cause rain. While the droplets remain small the maximum speed at which they fall through the air is low. Such droplets can be held aloft by the overall upward motion of the rising air. The rain comes when the droplets begin to grow larger - whether by colliding and coalescing with each other or simply by gradual growth from further condensation. Larger droplets are able to reach greater fall-speeds and they are then able to leave the cloud and drop to the ground.

The day-to-day variations in British weather that we experience are intimately connected with the passage of these storm systems eastward across our region. In subsequent blogs, we'll ask why these storms should form at all, look at how they affect European climate (i.e., the "average" weather), and examine how the storm tracks can be dramatically altered by changes in the jet-stream over the North Atlantic.

(David Brayshaw is based in the Department of Meteorology at University of Reading (www.met.reading.ac.uk). Further information about last December's cold UK weather in the UK can be found at https://www.walker-institute.ac.uk/news/Dec_2010/.

Kate Humble:

Kate Humble: Helen Czerski:

Helen Czerski: Stephen Marsh:

Stephen Marsh: Aira Idris:

Aira Idris:

Comments Post your comment