Thermal expansion of solids, liquids and gases

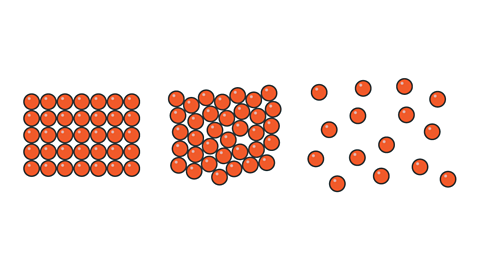

When almost all known solids, liquids and gases are heated they expand in size. This is called thermal expansionThe increase in volume of a solid, liquid or gas when its temperature increases and pressure remains constant.. This occurs when the surrounding pressureForce exerted over an area. The greater the pressure, the greater the force exerted over the same area. does not change.

This occurs because as the particles are heated they gain internal energyThe total kinetic energy and potential energy of the particles in an object. and they move more. When they do this, the volume, or overall size, of the object increases.

The particles in gases and liquids move more freely than in solids, so their volume increases when heated.

Demonstration of solid expansion

Ball and ring

If the ball fits through the ring at room temperature, heat the metal ball. It expands and will then not fit through the ring.

If the ball does not fit through the ring at room temperature heat the metal ring. The ring expands and the hole in the centre gets bigger. The ball will now fit through the ring.

The volume of different solid materials expand at different rates. Pouring hot water on the metal lid of a jam jar can make it easier to open the jar. This is because the metal lid expands more than the glass jar.

Rivets hold sheets of metal together. The rivet is heated up and hammered between two sheets of metal. The ends are then hammered flat. As the rivet cools, it contracts in volume and pulls the two sheets of metal tightly together.

Question

When building a train track, the engineer leaves a small gap between each section of track. Why?

If thermal expansion occurs on a hot day the tracks will expand. Leaving a small space for the tracks to expand into means they will not buckle.

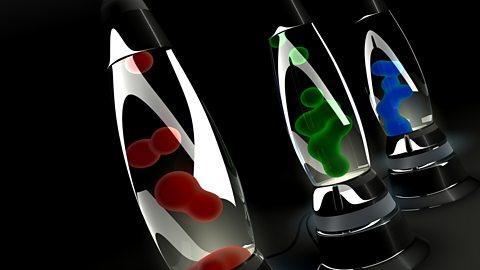

Demonstration of liquid expansion

Like solids, liquids expand when they are heated, but because the bonds between separate moleculeA cluster of non-metal atoms that are chemically bound together. are usually less tight, liquids expand more than solids.

The water level in the capillary tube is initially at A.

When the water is heated the liquid level initially falls to level B, before rising to level C and above.

When the glass flask and capillary tube are first heated, they expand. This causes the volume of the flask to increase, and the liquid level falls to B.

However, the liquid is quickly heated and starts to expand. It expands more than the solid glass and so the water level rises back to A and then up to, and beyond, C.

This shows that:

- Liquids expand when heated

- Liquids expand more than solids

This is the principle behind liquid-in-glass thermometers. An increase in temperature results in the expansion of the liquid which means it rises up the glass. The liquid used is usually alcohol or mercury.

Demonstration that gases expand

Gases also expand when heated.

Molecules within gases are further apart and weakly attracted to each other. Heat causes the molecules to move faster, which means that the volume of a gas increases more than the volume of a solid or liquid.

Once the flask stops being heated it cools and contracts. This causes the liquid to be sucked up the tube and into the flask.

Summary

- Matter expands when heated and contracts when cooled

- Liquids expand and contract more than solids

- Gases expand and contract more than liquids

The bimetallic strip

A bimetallic strip is made from two different metals riveted together, one on top of the other.

When heated, both metals expand, but one expands more than the other. Since they are riveted together, they cannot slip over one another, and the strip bends.

The metal which expands more is at the outside of the curve. The metals used are often brass and steel. Brass expands more than steel and so will be on the outside of the curve.

As the metal cools it straightens out again. It bends in the opposite direction if cooled down beneath room temperature.

A bimetallic fire alarm

When there is a fire:

- The temperature rises

- The brass expands more than the iron and will be on the outside of the curve

- The strip bends down and touches the contact

- The electric circuit is complete and the bell rings

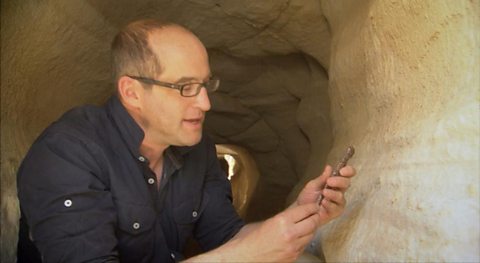

Video: Heating metals

Getting temperatures right isn't just something you need to do with living things.

Now these two bars are made of two different metals - brass and iron.

Now if I heat them in the same flame, brass expands more than the iron.

So if I fix them together, and then heat them in the same flame, what do you think will happen?

Both still expand but by different amounts and the force generated is big enough to bend the bars and in some jobs knowing this can be very important indeed.

Extended syllabus content: Forces of attraction

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about forces of attraction. Click 'show more' for this content:

Particles in solids, liquids and gases are held together by forces of attractionWeak attractive forces between molecules. When a simple molecular substance melts or boils, it is the intermolecular forces that are broken. between them. The forces of attraction between particles are weakest in gases, then liquids and are strongest in solids. This is the reason why gases expand the most when heated, followed by liquids and solids increase in volume the least.

Specific heat capacity

Heating materials

When materials are heated, the molecules gain kinetic energyThe energy an object possesses by being in motion. and start moving faster. The result is that the material gets hotter.

Key fact: Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of the molecules.

Different materials require different amounts of energy to change temperature. The amount of energy needed depends on:

- the mass of the material

- the substance of the material (specific heat capacity)

- the desired temperature change

It takes less energy to raise the temperature of a block of aluminium by 1°C than it does to raise the same amount of water by 1°C. The amount of energy required to change the temperature of a material depends on the specific heat capacityThe amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 kg of substance by 1°C. of the material.

Heat capacity

Key fact: The specific heat capacity of a material is the energy required to raise one kilogram (kg) of the material by one degree Celsius (°C).

The specific heat capacity of water is 4,200 Joules per kilogram per degree Celsius (J/kg°C). This means that it takes 4,200 J to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1°C.

Some other examples of specific heat capacities are:

| Material | Specific heat capacity (J/kg°/C) |

|---|---|

| Brick | 840 |

| Copper | 385 |

| Lead | 129 |

Lead will warm up and cool down fastest because it doesn’t take much energy to change its temperature. Brick will take longer to heat up and cool down. Bricks can be used in storage heaters as they stay warm for a long time.

Other heaters are filled with oil (1,800 J/kg°C) or water (4,200 J/kg°C) as these emit a lot of heat energy as they cool down and therefore stay warm for a long time.

Video: Specific heat capacity

Jonny Nelson explains specific heat capacity with a GCSE Physics practical experiment

Podcast: Heat capacity

In this episode James and Ellie explore specific heat capacity, how to calculate it and how it varies by substance.

JAMES: Hello and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics podcast.

ELLIE: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in Physics and combined science.

JAMES: I'm James Stewart, I’m a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I'm Ellie Hurer a bioscience PhD researcher.

JAMES: And just a quick reminder that whilst you're in the BBC Sounds app, there's also the Bitesize Study Support podcast, which is full of tips to help you stay focused during revision and get the best out of your exam day.

ELLIE: Yeah, it's definitely worth checking out. So okay, let's get started. Today we're going to be talking about specific heat capacity.

James, do you like cooking?

JAMES: I do, I do indeed.

ELLIE: What's your favourite thing to make?

JAMES: Oh, I love a good roast, but I'm also like so impatient and it gets, takes so much time, but when you get it, it's so satisfying. How about you, Ellie?

ELLIE: I’ll be honest. I just really love pasta.

JAMES: That's fine! I like it, good!

ELLIE: It’s quick, easy and delicious. And it's the example we're going to use a lot today as we talk about heat.

So, when you heat food, or any material, the particles heat up and transfer energy from their thermal energy store to their kinetic energy store and they start moving faster. Which is why you sometimes see your food sizzling away when you've warmed it up.

JAMES: Yeah, looks good, doesn't it? And as you'll note, if you've ever looked at all the settings on a microwave, different materials require different amounts of energy to change temperature.

The amount of energy they need depends on the mass of the material, how much you want the temperature to change, and the substance.

ELLIE: And that last one is what we're going to focus on, the substance of the material, because that's what determines a material's specific heat capacity.

JAMES: Specific heat capacity is the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by one degree Celsius. So in your case, Ellie, that will be the amount of energy you need to raise a temperature of one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius.

ELLIE: So, let's talk about how to calculate the change in thermal energy that occurs when we heat something up. Grab a pen and piece of paper because it's time for a formula.

JAMES: We need, like, a klaxon, don't we? Or a bleep or a buzzer of some kind there.

Okay, so change in thermal energy equals mass multiplied by specific heat capacity, multiplied by temperature change.

I'll say that again with the units that we measure those in. So change in thermal energy is measured in joules, and to calculate it we take the mass of a material, measured in kilograms, multiply it by the specific heat capacity, measured in joules per kilogram degrees Celsius, and then we multiply it by the temperature change measured in degrees Celsius.

ELLIE: So just take a note that you might have to change the mass of a material into kilograms. So you need to remember that 1,000 grams is equal to 1 kilogram.

JAMES: That's handy to know. My partner's a baker and like, that's every day in my house, the conversation, “How many kilograms is that?” like, every day.

ELLIE: So yeah, you can use this in everyday life.

JAMES: Yeah, literally. It applies to all circumstances.

ELLIE: So, let's talk about how to apply that to a practical example. Imagine it's a Friday night, you're chilling, and you want to boil some water to make some pasta.

JAMES: So you might take 0.5 kilograms of water and heat it up from 20 degrees Celsius to 100 degrees Celsius. And water has a specific heat capacity of 4,180 joules per kilogram per degree Celsius. So how would you work that out? I'll give you a few seconds to take the equation, write it down and calculate it for yourself.

ELLIE: Okay, did you finish your calculations? Let me explain. So, you would multiply 0.5 kilograms by 4,180 joules per kilogram per degree Celsius. Then, you'd multiply that by the 80 degrees Celsius temperature change to get the answer…

JAMES: 167,200 joules.

ELLIE: That's correct.

JAMES: Wahoo!

ELLIE: Woo!

JAMES: So imagine you wanted to make some iced coffee. I love iced coffee.

ELLIE: That's my favourite.

JAMES: Yes, always my order. Even if you made your hot coffee and gave it a few minutes to cool down, it still wouldn't be cool enough as a refreshing cool drink on a summer's day. So, you'd pop it in the fridge, wouldn't you?

ELLIE: Yeah, but how would you calculate the thermal energy change between you putting it in the fridge and then taking it out to drink the next day? Well, it's time to grab your pen and paper again because it's time for another calculation.

JAMES: The equation to calculate change in thermal energy is mass multiplied by specific heat capacity, multiplied by temperature change.

ELLIE: So, if the mass of the coffee was, say, 0.2 kilograms, the specific heat capacity of the coffee was 4,180 joules per kilogram. And if it was cooled down from 80 degrees Celsius to 3 degrees Celsius, how would you calculate the thermal energy change?

JAMES: If you missed a measurement in that or you missed the equation, be sure just to rewind 30 seconds and listen back, no problem. We'll give you a few moments to pause, write that down and calculate it.

Okay, so to calculate the heat change, you would simply multiply 0.2 kilograms by 4,180 joules per kilogram per degree Celsius. Then you multiply that by minus 77 degrees Celsius temperature change to get the answer…

ELLIE: Minus 64,372 joules

JAMES: Yes, that's right. And look, we know there's a lot of numbers and measurements in what you've just heard, so be sure to check out the BBC Bitesize energy and heating pages to read the formula and apply it to your own range of examples.

ELLIE: So, it's that time that we need to go through key points that we've learned today. So firstly, different materials require different amounts of energy to change temperature. Also, the specific heat capacity of a substance is the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of the substance by one degree Celsius.

And finally, the equation to calculate change in thermal energy is: change in thermal energy is equal to mass multiplied by the specific heat capacity, multiplied by temperature change.

JAMES: Alright, so those are some of the key facts you need to know about specific heat capacity and in the next episode, we're going to be talking about how to apply what you've learnt to the practical every day. So, get ready to get stuck into that.

ELLIE: Thank you guys for listening again to BBC Bitesize Physics. If you found this helpful, go back and listen again and make some notes so you can come back to this as you revise.

BOTH: Bye!

Calculating thermal energy changes

The amount of thermal energy stored or released as the temperature of a system changes can be calculated using the equation:

change in thermal energy = mass × specific heat capacity × temperature change

\(\Delta E_{t}=m \times c \times \Delta \Theta\)

This is when:

- change in thermal energy (ΔEt) is measured in joules (J)

- mass (m) is measured in kilograms (kg)

- specific heat capacity (c) is measured in joules per kilogram per degree Celsius (J/kg°C)

- temperature change (∆θ) is measured in degrees Celsius (°C)

Example

To boil 0.25 kg of water it first needs to be heated from 20°C to 100°C. If the specific heat capacity of water is 4,180 J/kg°C, how much thermal energy is needed to get the water up to boiling point?

\(E_{t} = m~c~\Delta \theta\)

\(E_{t} = 0.25 \times 4,180 \times (100 - 20)\)

\(E_{t} = 0.25 \times 4,180 \times 80\)

\(E_{t} = 83,600~J\)

Question

How much thermal energy does a 2 kg steel block (c = 450 J/kg°C) lose when it cools from 300°C to 20°C?

\(>E_{t} = m~c~\Delta \theta\)

\(E_{t} = 2 \times 450 \times (300 - 20)\)

\(E_{t} = 2 \times 450 \times 280\)

\(E_{t} = 252,000 J\)

Practical experiment - measuring specific heat capacity

There are different ways to investigate methods of insulation. In this practical activity, it is important to:

- make and record potential difference, current and time accurately

- measure and observe the change in temperature and energy transferred

- use appropriate apparatus and methods to measure the specific heat capacity of a sample of material

Podcast: Specific heat capacity practical

In this episode, Ellie and James discuss the specific heat capacity practical experiment. They outline how the experiment is carried out and share key tips for how to get reliable results.

ELLIE: Hello and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics podcast.

JAMES: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in Physics and combined science. I'm James Stewart, I'm a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I'm Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher. Before you listen, just a reminder that you can listen to the whole series or find an episode that you want to focus on. Whatever works for you.

JAMES: Okay, let's get started. Today we're going to be talking about the specific heat capacity practical. So Ellie, you might be wondering why we're wearing lab coats today.

ELLIE: Yeah, I was a little bit confused when I saw your text saying we needed lab coats, safety goggles and a clipboard to record a podcast. It's not exactly a dangerous activity.

JAMES: It’s a serious job, Ellie. You never know when a microphone might jump at you, a script might give you a paper cut or a listener might leave a mean comment because, well, they don't like our jokes.

ELLIE: Our jokes are great, so that's not going to happen.

JAMES: Ha, ha, ha. Look, we're off topic. The reason we're in lab coats today is that part of GCSE physics includes a practical activity all about specific heat capacity. Finally, a practical.

If you haven't listened to that episode about specific heat capacity, please do pause, go back and listen and then return to this episode and come back and do it with us. As a quick reminder, specific heat capacity is the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by one degree Celsius.

ELLIE: And when it comes to your GCSE, you'll carry out a practical investigation to determine the specific heat capacity of one or more materials. Let's try an example.

JAMES: As a heads up, we're gonna go through quite a few definitions and steps you'll need to understand for this practical. So, classic us, if you haven't already, get your pen, get your paper and let's do it together.

So in this practical, the aim of the experiment is to find out the specific heat capacity of a sample of material.

ELLIE: The independent variable is the material the block is made from. In this case, you'll use an aluminium block that will have two holes drilled into the top that don't go the whole way through.

JAMES: The dependent variable is the specific heat capacity value, and the control variables are the time the heater is on for and the mass of the material used.

ELLIE: Okay, so let's walk through how you would do the experiment step-by-step. So step one, unless you know your block is exactly one kilogram, measure the mass of the block using a balance.

JAMES: Step two, place the immersion heater into the central hole at the top of that aluminium block.

Step three, place the thermometer into the smaller hole of the block and put a couple of drops of oil into it just to make sure the thermometer is surrounded by hot material.

ELLIE: And step four, fully insulate the aluminium block by wrapping it loosely with cotton wool.

And step five, record the starting temperature of the block.

JAMES: Yeah, so far so good. Step six, connect the heater to the power supply and of course don't forget to turn the power supply on. Time it for 10 minutes and then turn the power supply off again. There also needs to be an ammeter in the circuit so the current can be measured.

And then finally, step 7, after 10 minutes the temperature will still rise, even though the heat has been turned off, and then it will begin to cool. So, record the highest temperature that it reaches and calculate the temperature rise during the experiment.

ELLIE: And as you do the practical, you'll need to measure four key things. The current reading from the ammeter, the voltage reading from the power supply, the initial temperature in degrees Celsius, and then the final temperature also in degrees Celsius.

JAMES: And when you do this practical in class, you'll then take your measurements and analyse them to calculate the specific heat capacity of the block of metal you used.

ELLIE: And to learn more about the equation you need to use to calculate this, head over to the Bitesize website to read more.

JAMES: Then repeat the whole method with another material, as that is the independent variable being investigated.

ELLIE: Always remember that no experiment is perfect. Sometimes we run into something called an experimental error, which is when our results aren't completely accurate because of other variables.

So, can you think of any we might find in this experiment?

JAMES: Well, one variable could be that not all of the heat from the immersion heater will actually heat the aluminium block. Some will be lost to the surroundings.

ELLIE: Exactly, James. That means that more thermal energy is transferred than is necessary for the aluminium block alone, because some of the energy is transferred to the surroundings.

JAMES: Which means the final result of our specific heat capacity will be higher than what is actually needed for one kilogram of aluminium alone. So, it's really important to know that other variables will affect your practical.

ELLIE: Because this is a practical experiment, there are some things we need to do to make sure the experiment is safe and that the results are accurate.

JAMES: Yeah, in this experiment we're working with an immersion heater, which can get very hot very quickly, which of course is a hazard, it can burn our skin. So, what measures Ellie, should we take to control that hazard?

ELLIE: Well, firstly, you wouldn't touch the heater when it's on. You would also position the apparatus away from the edge of your bench to reduce the risk of it falling. As well as that, once you're done with it, you would give the heater time to cool down before packing it away. Sometimes you'll be given a method that isn't quite right and the exam will ask you to suggest how to improve it. In that case, you should compare the method in the exam to the one you've learned and see what's different.

JAMES: For example, they may give you a step-by-step method that doesn't mention insulating the block. In that case, the improvement will be to insulate the block to minimise the loss of energy in the surroundings.

ELLIE: So, here are some key things you need to remember. The aim of the experiment is to find out the specific heat capacity of a sample of material.

Two, during the practical, you need to record the temperature change, current and mass of the aluminium block.

And finally, one of the potential hazards of this practical is accidentally burning yourself. You can avoid this by not touching the heater when it's on and positioning the apparatus away from the edge of your bench.

JAMES: You'll learn more about this practical when you're in the class, but be sure to pay attention and make notes on everything that we mentioned here when it comes to practicing that experiment.

ELLIE: And, again, don't forget to stay safe and never touch a heater when in use.

So those are some of the key things you need to know for your practical investigation. In the next episode, we're going to be talking about power, so stay tuned.

JAMES: You sound like you're excited about that one.

ELLIE: Yeah. Woo!

JAMES: Thank you for listening to Bitesize Physics. As always, if you found this helpful, you can of course go back and listen again, make some notes along the way and come back here whenever you want to revise.

ELLIE: There's also so many resources available on the BBC Bitesize website, so be sure to check it out.

BOTH: Bye!

Aim of the experiment

To measure the specific heat capacity of a sample of material.

Method

- Place the immersion heater into the central hole at the top of the block of material.

- Place the thermometer into the smaller hole and put a couple of drops of oil into the hole to make sure the thermometer is surrounded by hot material.

- Fully insulate the block by wrapping it loosely with cotton wool.

- Record the temperature of the block.

- Connect the heater to the power supply and turn it off after ten minutes.

- After ten minutes the temperature will still rise even though the heater has been turned off and then it will begin to cool. Record the highest temperature that it reaches and calculate the temperature rise during the experiment.

Record results in a suitable table. The example below shows some sample results.

| Ammeter reading (A) | Voltmeter reading (V) | Initial temperature (°C) | Final temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.65 | 10.80 | 15 | 38 |

Analysis

The block has a mass of 1 kg and the heater was running for 10 minutes = 600 seconds.

Using the example results:

energy transferred = potential difference × current × time

\(E = V \times I \times t\)

\(E = 10.90 \times 3.65 \times 600\)

\(E = 23,700~J\)

\(E = mc \Delta T\)

\(c = \frac{E}{m \Delta T}\)

\(c = \frac{23,700}{1 \times (23)}\)

\(c = 1,030 J/kg°C\)

The actual value for the specific heat capacity of aluminium is 900 J/kg°C. The calculated value does not match exactly but it is in the correct order of magnitude.

Evaluation

All experiments are subject to some amount of experimental error due to inaccurate measurement, or variables that cannot be controlled. In this case, not all of the heat from the immersion heater will be heating up the aluminium block, some will be lost to the surroundings.

More energy has been transferred than is needed for the block alone as some is transferred to the surroundings. This causes the calculated specific heat capacity to be higher than for 1 kg of aluminium alone.

Hazards and control measures

| Hazard | Consequence | Control measures |

|---|---|---|

| Hot immersion heater and sample material | Burnt skin | Do not touch when switched on. Position away from the edge of the desk. Allow time to cool before packing away equipment. Run any burn under cold running water for at least 10 minutes. |

Practical experiment - Measuring the specific heat capacity of water

There are different ways to determine the specific heat capacity of water. In this required practical activity it is important to:

measure and observe the change in temperature accurately

use the appropriate apparatus and methods to measure the specific heat capacity of water

Aim of the experiment

To measure the specific heat capacity of water.

Method

- Place one litre (1 kg) of water in the calorimeterA machine used to measure the energy involved in a chemical process.

- Place the immersion heater into the central hole at the top of the calorimeter.

- Clamp the thermometer into the smaller hole with the stirrer next to it.

- Fully insulate the calorimeter by wrapping it loosely with cotton wool.

- Record the temperature of the water.

- Connect the heater to the power supply and a joulemeter and turn it on for ten minutes. Stir the water regularly.

- After ten minutes the temperature will still rise even though the heater has been turned off and then it will begin to cool. Record the highest temperature that it reaches and calculate the temperature rise during the experiment.

Results

Record results in a suitable table. The example below shows some sample results.

| Energy supplied (J) | Initial temperature (°C) | Final temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 100,000 | 15 | 38 |

Analysis

The water has a mass of 1 kg and the heater supplied 100,000 J, whilst the temperature rose 23°C.

Using the example results:

\(c = \frac{\Delta Q}{m\Delta \theta }\)

\(c = \frac{100,000}{1 \times 23} = 4,300~J/kg {\textdegree}C\)

The actual value for the specific heat capacity of water is 4,200 J/kg°C. The calculated value does not match exactly but it is in the correct order of magnitude.

Evaluation

All experiments are subject to some amount of experimental error due to inaccurate measurement or variables that cannot be controlled. In this case, not all of the heat from the immersion heater will be heating up the water, some will be lost to the surroundings.

More energy has been transferred than is needed for the block alone as some is transferred to the surroundings. This causes the calculated specific heat capacity to be higher than for one kilogram (kg) of water alone.

The lid on the calorimeter has reduced much thermal energy loss, and the use of cotton wool insulation has also helped to insulate the calorimeter. Thicker insulation would improve the accuracy of the results even more.

Hazards and control measures

| Hazard | Consequence | Control measure |

|---|---|---|

| Hot immersion heater and sample material | Burn skin | Do not touch when switched on. Position away from the edge of the desk. Allow time to cool before packing away equipment. Run any burn under cold running water for at least 10 minutes. |

Changes of state

Melting, evaporating and boiling

Energy must be transferred, by heating, to a substance for these changes of stateSolid, liquid or gas. Evaporation is a change of state from liquid to gas. to happen. During these changes the particles gain energy, which is used to:

- break some of the bondThe chemical link that holds molecules together. between particles during meltingThe process that occurs when a solid turns into a liquid when it is heated.

- overcome the remaining forces of attraction between particles during evaporationThe process in which a liquid changes state and turns into a gas. or boilChanging from the liquid to the gas state, in which bubbles of gas form throughout the liquid.

During melting and boiling there is not a change in temperature because the energy breaks the bonds or forces of attraction.

In evaporation, particles leave a liquid from its surface only. In boiling, bubbles of gas form throughout the liquid. They rise to the surface and escape to the surroundings, forming a gas.

Evaporation causes an object to cool. When sweat evaporates from skin it cools it down.

The amount of energy needed to change state from solid to liquid, and from liquid to gas, depends on the strength of the forces between the particles of a substance. The stronger the forces of attraction, the more energy is required.

Every substance has its own melting pointThe temperature at which a solid changes into a liquid as it is heated. and boiling pointThe temperature at which a substance rapidly changes from a liquid to a gas. The stronger the forces between particles, the higher its melting and boiling points.

The strength of the forces between particles depends on the particles involved. For example, the forces between ions in an ionicrelating to, composed of, or using ions. solid are stronger than those between molecules in water or hydrogen. This explains the melting and boiling point data in the table.

| Substance | Bonding type | Melting point | Boiling point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | Ionic | 801°C | 1413°C |

| Water | Small molecules | 0°C | 100°C |

| Hydrogen | Small molecules | -259°C | -252°C |

These boiling/melting points are for standard atmospheric pressure and will be different at higher/lower atmospheric pressures. Evaporation can take place below the boiling point of a substance.

Condensing and freezing

Energy is transferred from a substance to the surroundings when a substance condenses or freezes. This is because the forces of attraction between the particles get stronger.

Condensing occurs at the boiling point of a substance. A gas has particles with high kinetic energy stores. As the gas cools these stores reduce. When the cooling gas lowers to its boiling point, it condenses into a liquid. The particles move closer together.

Freezing occurs at the melting point. As a liquid cools down the kinetic energy stores of its particles reduce. When the cooling liquid reaches its melting point, it solidifies (or freezes if water) into a solid. The particles move closer together to form the fixed, regular arrangement seen in solids.

Predicting a physical state

The state of a substance at a given temperature can be predicted if its melting point and boiling point are known. The table summarises how to work this out.

| Temperature | Predicted state |

|---|---|

| Given temperature < melting point | Solid |

| Given temperature is between melting and boiling points | Liquid |

| Given temperature > boiling point | Gas |

Question

The melting point of oxygen is -218°C and its boiling point is -183°C. Predict the state of oxygen at -200°C.

Oxygen will be in the liquid state at -200°C (because this is between its melting and boiling points).

Limitations of the particle model

The particle model assumes that particles are solid spheres with no forces between them. However:

- particles are not solid, since atoms are mostly empty space

- many particles are not spherical

Extended syllabus content: Difference between boiling and evaporation

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know the difference between boiling and evaporation. Click 'show more' for this content:

The table below summarises the differences between boiling and evaporation.

| Boiling | Evaporation |

|---|---|

| Fast | Slower |

| Can occur throughout the liquid | Occurs from the surface only |

| Produces bubbles | Does not produce bubbles |

| Does not result in cooling | Results in cooling |

| Occurs at the boiling point | Occurs below the boiling point |

Evaporation occurs at a faster rate when:

- the liquid is at a higher temperature because the particles have a greater store of kinetic energy

- the surface area of the liquid is greater

- the air above the liquid is moving (e.g. on a windy day).

Unlike boiling, evaporation cools the liquid. When sweat evaporates from skin it cools it down because the particles with the most kinetic energy usually evaporate quickest.

As the particle with the highest kinetic energy leave the surface of the skin, the average kinetic energy of the surface of the skin decreases, causing the temperature of the skin to reduce.

Quiz

Test your knowledge with this quiz on thermal properties.

More on Thermal physics

Find out more by working through a topic

- count3 of 4

- count4 of 4

- count1 of 4