Key points

- Charles I became King of England in 1625. He fell out with the English Parliament for several reasons.

- The disputes escalated into a civil war in 1642.

- After nearly seven years of war, Charles was defeated and put on trial for treason in 1649.

- After further conflict, the Civil Wars finally came to an end in 1651.

Game - Charles I

Play a History Detectives mission exploring Charles I's role in starting the English Civil Wars.

You can also play the full game.

Video about the English Civil Wars

Narrator:

The English Civil Wars were a series of battles fought between the Cavaliers, who supported the king, and the Roundheads, who supported Parliament. King Charles I believed, like all the kings and queens before him, that God had given him the divine right to rule the country and his decisions should not be questioned.

Parliament believed that the king's powers should be limited by them. At the time, Parliament was at the mercy of the king, and would only be called upon if the king wanted to raise taxes or pass legislation. The king refused to call upon Parliament for many years and governed on his own.

He changed religious practices and raised taxes, both of which upset many people in the country. By 1640, the king was forced to call upon Parliament as he needed more money to fight a war with Scotland. MPs in Parliament demanded reforms for the way the country was run, but the king refused. The country descended into the First Civil War in 1642.

The Cavaliers and the Roundheads fought their first battle at Edgehill in October, but there was no clear winner. Each side won smaller battles, but the Roundheads, with decisive input from the cavalry of Oliver Cromwell, won a major victory at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644, securing control of northern England. Further victories for the Roundheads followed in the summer of 1645, most notable at the Battle of Naseby.

The Cavaliers and the king were forced to surrender. The victors agreed that the imprisoned king should have limited powers, but still be on the throne. But there were many different groups now competing for political control of the country. Charles took advantage and made an agreement with Scotland to help him regain his old powers.

As the Scots invaded, Royalist uprisings happened across the country. The Second Civil War began in 1646. Ultimately, Charles and his supporters were defeated at the Battle of Preston in 1648. Cromwell and the Roundheads blamed the king for causing unnecessary death and bloodshed with the civil wars.

Charles I was tried and found guilty of high treason. He was executed in January 1649 in London. An event like this had never been seen before. The king, who many thought had been chosen by God to rule the country, had been executed. Oliver Cromwell ruled the country as Lord Protector until his death in 1658.

The monarchy was eventually restored with limited political powers in 1660, but the victory of Parliament over the king shapes the British political system to this day.

Charles' early reign

Charles I became King of England in 1625 following the death of his father, James I. He married a French princess, Henrietta Maria. This caused concern among some MPMember of Parliament- a politician who represents a particular area of the country, known as a constituency, and votes on laws., who believed Charles had plans to make England a CatholicA member of the Catholic Church. Catholics believe in having a hierarchy of priests and bishops beneath the Pope, who is the Head of the Church. Members of the Catholic Church also believe in devotion to the saints and the Virgin Mary, Jesus' mother, and in holding Mass. country again. England had been a Protestant country since the late 1500s, so this represented another big change after many years of religious upheaval.

Charles also believed in the Divine Right of Kings. This was the belief that he had been put in charge of the country by God, so therefore did not need assistance from Parliament in order to make decisions.

In 1625, one of Charles’ closest advisors, the Duke of Buckingham, led a failed naval battle against the Spanish at Cadiz. Charles refused to criticise Buckingham, which further angered some in Parliament.

In 1629, Parliament became increasingly critical of Charles’ decision making and policies. Charles decided to dissolveTo send away or break up a group. Parliament and rule without them. Parliament did not sit again until 1640.

Key events leading up to the outbreak of war in 1642

1629 - 1640

Without Parliament, Charles was not allowed to raise new taxes. To get around this, Charles introduced ship moneyA tax that was collected from people who lived in coastal towns during the Middle Ages, to help pay for the navy. Charles reintroduced this tax in 1635, and made people who lived inland pay it, too. in 1634. This was extremely unpopular, as this tax had only ever been raised during times of war.

In 1633, Charles had appointed William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury. This was an unpopular appointment, as Laud had some controversial ideas. For example, he ordered churches to have stone altars, rather than wooden communion tables. Stone altars were a feature of Catholic churches, so this added to some people’s fears that Charles intended to make England a Catholic country again.

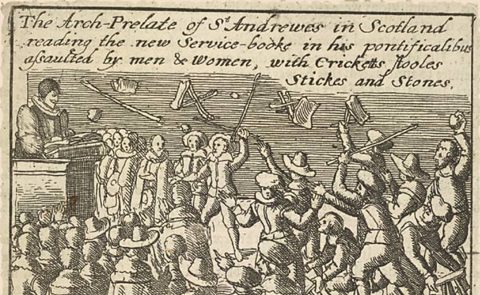

In 1637, Charles ordered the use of a new prayer book in Scotland, which angered Scottish PuritanVery strict Protestants who believed that the Church still required further reform to remove all trace of Catholic practices.. They believed that the Church needed to become more Protestant, and that the Church should be ‘purified’ of all traces of Catholic practice. People rioted when clergy used the prayer book in church services.

In 1640, angered by Charles' religious changes and interference, Scottish CovenantersA group of Scottish lords who promised to keep their chosen forms of worship and ways of running their churches, and to resist King Charles I's attempts to reform the Scottish Church. invaded the north of England. Charles was in urgent need of money. He had to recall Parliament to try and raise some new taxes to fund an army.

1640 - 1645

Knowing that Charles was in desperate need of money to fight Scotland, Parliament placed heavy demands on him in return for their support. Parliament demanded the arrival of two of Charles’ most trusted advisors, Archbishop Laud and the Earl of Strafford.

Strafford had been Lord DeputyThe representative of the monarch in Ireland during English rule. in Ireland, and the new Parliament attempted to impeachmentA process in which Parliament would bring legal action against a person in a role that gives them power over the public, on the basis that they had committed offences that abused their power. him on a range of different charges relating to his time there. Strafford was accused, for example, of offering to bring an Irish army over to England to fight the king’s opponents. Charles had to agree to meet with Parliament at least every 3 years.

In December 1641, Parliament narrowly voted in favour of the Grand Remonstrance. This was a list of demands for Charles to make further reforms. Even some MPs felt this went too far. Charles refused to agree to the Grand Remonstrance.

In January 1642, Charles went into the Houses of Parliament to try and arrest 5 MPs, but they had been warned of his arrival and escaped on the River Thames.

In August 1642, Charles grew tired of Parliament’s demands and raised his standardAn object, such as a flag or banner displaying the royal coat of arms, which is used in battle. at Nottingham, to declare war on Parliament.

Why did not all MPs support the Grand Remonstrance?

Up to 1640, most MPs had been unhappy with the way Charles was ruling. They felt he was not consulting them enough and needed to work with Parliament to successfully run the country.

However, there were some MPs who felt the Grand Remonstrance in December 1641 went too far. It contained over 200 points, asking Charles for further changes and demands. The vote only just passed, by 159 to 148. Many MPs believed in the Divine Right of Kings, and felt the Grand Remonstrance was going against this.

The demands further damaged the already tense relationship between Charles and Parliament, and the Grand Remonstrance is seen as one of the key causes of the Civil War.

Key events of the Civil War

The war was fought between two armies:

- The ParliamentarianA person who supported Parliament during the English Civil Wars., or ‘Roundheads’. They were given this name because they had much shorter haircuts compared to the long, curly wigs worn by Charles and his supporters.

- The RoyalistA person who supported King Charles I during the English Civil Wars., or ‘Cavaliers’. This name comes from the French term chevalier, which refers to a knight who rides a horse. The Parliamentarians originally used this term as an insult to the Royalists, but they eventually began to use it to refer to themselves.

There was a split in the country, with people supporting both sides.

The Battle of Edgehill, 1642

The first time the Royalist and Parliamentary forces directly fought each other was at Edgehill, in Warwickshire. Neither side won a convincing victory. Both sides mainly had inexperienced soldiers, which made it difficult for anyone to win the war quickly.

1642 - 1645

Charles had some success in the first two years of the war, but the momentum changed when Parliament decided to form a more professional army. Thomas Fairfax became commander-in-chief of the troops and Cromwell was in charge of the cavalrySoldiers on horseback..

The Battle of Naseby, 1645

By this time, the Parliamentarians has assembled the New Model ArmyA professional parliamentary army established in 1645 and led by Thomas Fairfax. It was mainly made up of experienced soldiers. It was a key factor in defeating the Royalist army.. Thomas Fairfax led this new, professional army at Naseby. The Royalists were led by Charles and Prince Rupert.

Naseby was a decisive victory for Parliament. The Royalists lost over 5,000 men- either injured, killed or taken prisoner. Much of their equipment and weapons were also captured. The extent of the defeat meant Charles did not have the resources to put up effective resistance. Charles fled to seek support from the Scots, but was handed over to Parliament in exchange for £100,000 in January 1647.

The Second Civil War

Charles escaped from Hampton Court, where he was being held, in November 1647. He travelled back to Scotland. He won support from Scots who said that they would invade England with him, to help him regain the throne. In return for their support, Charles agreed to make religious reforms.

The invasion, along with uprisings from Royalist supporters in England, started in May 1648. By August they had all been defeated. Charles was captured again. He tried to negotiate a settlement with Parliament, but Oliver Cromwell was opposed to this. Charles was charged with treason and put on trial in January 1649. To find out more about Charles' trial, read this guide.

What was the role of women during the Civil Wars?

There were lots of examples of women being directly involved in the Civil Wars. Some women wore men’s clothing and armour so that they could join the fighting. A woman called Nan Ball was caught fighting for the Royalist army in 1642, apparently because she did not want to be separated from her husband. A law was drafted by Charles in 1643 to ban women from wearing men’s clothes and fighting for the Royalist army.

Women did not just fight in the War. Elizabeth Alkin was a nurse who treated injured Parliamentarian soldiers. However, she also acted as a spy, and passed information to Parliament. Constance Stringer was a spy, too, informing Parliament about who was fighting for Charles.

Game - women in the Civil Wars

Play a History Detectives mission exploring how women's rights changed during the Wars.

You can also play the full game.

Video - Impact of the Civil Wars on ordinary people

Watch this video to find out what primary sources can tell us about how the lives of ordinary people were impacted by the Civil Wars.

Presenter:

I’m standing outside Parliament, where the country is ruled from today. But we should remember that it took brutal civil war, fought by men here like Oliver Cromwell, to establish the power of Parliament and to make sure that monarchs respected that power.

The Civil Wars of the 1640s were perhaps the most violent and destructive episodes in British history. This was a struggle between King Charles I and Parliament over how, and in whose interests, the country should be governed.

But what about the soldiers themselves, and the people caught in the firing line? I’m here at the National Archives in Kew to find out more about what sources can tell us about them.

The Civil War divided the nation and it had a terrible effect upon ordinary people. Here at Kew, they’ve got this wonderful book of bound letters. This one here is by an officer in the Parliamentary army, Nehemiah Wharton, and he wrote it to an acquaintance. In this letter, written during the early stages of the Civil Wars, he describes a range of actions by the opposing Royalist troops: “Certain gentlemen of the country informed me that Justice Edmund, a well-spoken man, was robbed by the vile bluecoats of Colonel Chomley’s regiment and lost even their beds”.

Later, in the same letter, he writes: “We had news that Prince Rupert, that evil Royalist, had surrounded Leicester and demanded £2000 or else threatened to plunder the town”.

We could dismiss this source as being biased towards the Parliamentary side of the argument, but all sources are biased in their own way. It does tell us about the effects of the war upon civilians. The first source is a soldier’s observations of the scale of human suffering, but what about those people on the receiving end?

Other sources reveal that the war was having a huge impact on ordinary people on both sides.

Here I have a second source relating to the Civil War. It’s a petition or a plea to a County Committee- the County Committees were instructed by Parliament to raise taxes in support of the Parliamentarians’ war effort. This particular one outlines the case of a woman named Mary Baker. It says, “Mary’s husband is in very poor health, his whole estate has been seized, and so he cannot pay an extra 20th part or 5%. Yet a warrant was issued against Mary’s husband to pay the rest”.

Mary is begging on behalf of her husband here, so, on the face of it, the situation seems pretty bad. Now it could be that they are just exaggerating in order to get out of paying their taxes. But the shelves here at the National Archives contain many other cases like this one.

In the first source, the Royalists were doing the plundering. Here, in this source, it seems as though the Parliamentarians are doing their own type of plundering.

The two sources we’ve looked at give us a great sense of the war’s immediate impact upon men and women. But we need a longer-term picture. And here’s a source that provides it.It’s a petition from a group of widows in Liverpool, and it gives us a sense of the devastating impact of the war on whole communities. It talks about the effects on, “the many hundreds of widows and fatherless children, whose husbands and fathers lost their lives and estates”.

What we get from this source over and above the other two in an impression of the sorry state that the women and children were left in as a result of the war. “Houses were burned and many of your petitioners’ husbands were barbarously massacred and the rest imprisoned and all despoiled and robbed of their estates”.

The petition blames the Royalist army for the carnage and plunder. And in this source, they’re saying to Parliament, “we supported you, we made sacrifices and now we want compensation for this”.

The sources we’ve looked at take us beyond the textbooks and their usual focus on leaders like Oliver Cromwell. The story of war is the story of how it affected ordinary men, women and children, people like Nehemiah Wharton, who described his experiences as a soldier. Or Mary Baker, who pleaded for compensation after her property and possessions were plundered. Or the Liverpool widows, whose lives were devastated by the conflict.

The sources we’ve looked at today show us how the Civil War affected ordinary people like you and me.

Game - ordinary people in the Civil Wars

Play a History Detectives mission exploring who was affected by the Civil Wars.

You can also play the full game.

Test your knowledge

Play the History Detectives game! gamePlay the History Detectives game!

Analyse and evaluate evidence to uncover some of history’s burning questions in this game.

More on The English Civil Wars

Find out more by working through a topic

- count2 of 3

- count3 of 3