When it comes to liquids, water is about as ordinary and boring as it gets, right? Wrong.

Just because it’s something we encounter constantly throughout our day, doesn’t mean that we’ve got water all figured out. In fact, there some things about water that might actually surprise you.

Let's delve into some of the weird ways water defies our expectations.

Boiling waters appears to levitate

Don’t try this at home, but if water droplets come into contact with an extremely hot surface, they sometimes appear to hover.

Normally, if you dropped water onto a hot surface the water would start to hiss and sizzle as it boiled, before quickly evaporating. However, if the surface is hot enough, the water will act a little differently. It will bead up into tiny little balls which are able to skitter around the surface.

This phenomenon is known as the Leidenfrost effect, named for the 18th Century German scientist Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost, who first described it. Some people use it in cooking to help them gauge just how hot a pan is.

As the water makes contact with the heated surface, the bottom of the droplet instantly boils and evaporates, becoming steam. This thin layer of steam acts as insulation between the water and the hot surface, so the droplet appears to hover, suspended in the air. Without direct contact with the heat source, it takes longer for the remaining water to evaporate, so the droplet hangs around longer.

There isn’t an exact temperature at which the Leidenfrost effect occurs, because it depends on a number of different factors. But it tends to happen on a surface heated to between 180° C and 200° C.

Boiling water can move uphill

Scientists have also discovered that the flow of steam can be guided in a certain direction, by simply changing the temperature and texture of the surface.

If the heated surface is jagged, with triangular teeth a bit like a saw, most of the steam will flow upwards in one direction. With the droplets floating on top, like a leaf on a river, they follow the same flow. Watching water droplets move up a hill looks very odd, but it can be done on inclines of up to 12 degrees.

Image source, BBC

Image source, BBCIce can float on water

Okay, so we’re stating the obvious here. Everyone knows that ice can float on water, we see it happen all the time. From ice cubes in a refreshing drink, to icebergs out in the ocean.

But have you ever thought about how odd it is that the solid form of water is able to float on the liquid version?

Typically, we’d expect the solid form of a material to be denser than the liquid one, and so it should sink. Water is a bit different though. It’s actually less dense as a solid than it is as a liquid. Ice has a density of 0.9 g/cm3 whereas water has a density of 1.0 g/cm3. This unusual characteristic is the result of water’s structure.

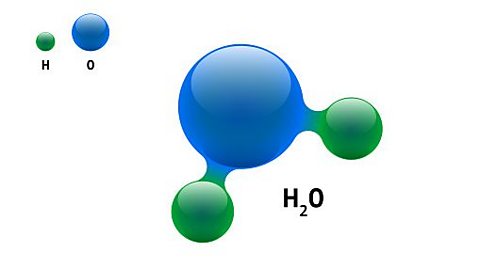

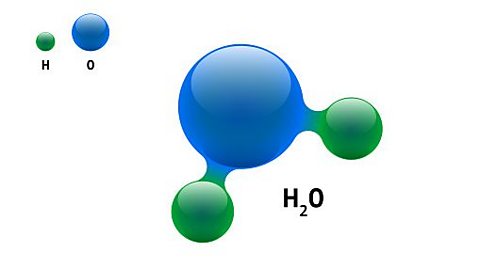

The chemical formula for water is H2O, meaning that each water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. These are joined in a kind of V-shape, with a hydrogen atom either side of the oxygen atom.

The two types of atoms are held together by covalent bonds. This means that they share a pair of electrons. It’s an incredibly strong bond that takes a lot of energy to break.

Image source, BBC

Image source, BBC Image source, azatvaleev

Image source, azatvaleevHowever, the electrons have a tendency to cluster around the oxygen atom, which pulls on them more strongly. As a result, the two hydrogen atoms are left with a slight positive charge. This allows them to attract the negatively charged oxygen atoms of other water molecules. These oxygen and hydrogen atoms bond together, in what is known as a hydrogen bond.

As a liquid, water molecules have a lot more energy. The hydrogen bonds are constantly forming and then breaking, so the molecules continue to move around. As the water molecules lose energy and turn to ice, the hydrogen bonds form a regular hexagonal structure. In this very open structure, the water molecules are spaced further apart than they are as a liquid.

This decreases the overall density of the ice, allowing it to float on water.

Image source, azatvaleev

Image source, azatvaleevSalt makes it harder for water to freeze

The freezing point of water is 0° C, which is when it turns to ice.

However, if you add salt to the water, the freezing point of water is lowered. How low it goes depends on the ratio of salt to water, known as salinity. For example, seawater typically has a salinity of 3.5%, which lowers the freezing point to around -1.8° C. At 0° C, saltwater will simply remain liquid. This is known as freezing point depression.

But why does salt have this effect?

Salt is a solute, which means that it is able to dissolve in water. Take the example of sodium chloride (table salt), which has the chemical formula NaCl. When it is dissolved in water, the salt separates into sodium and chloride ions. These ions get in the way of the water molecules and prevent them from easily forming the rigid hexagonal structure of ice, as explained above.

We make use of salt’s incredible ability to prevent water freezing every winter, when we throw salt on our paths and roads.

The salt dissolves in any moisture already present on the ground surface, creating a saline solution and lowering the freezing point. This makes it a lot more difficult for any ice to form, or snow to stick. Timing is everything when it comes to gritting, as the salt needs to mix with the water before it’s frozen.

How winter works: Six winter mysteries solved

We spoke to Dr Sylvia Knight of the Royal Meteorologist Society to answer six very important cold weather questions.

The science behind real life ice magic

Hair ice? Ice pancakes? Diamond dust? Here's the science behind these magical ice phenomena.

What does Star Wars get right about physics?

Don't worry, there's plenty it gets wrong too.