'It doesn't look African' - challenging stereotypes at Tate Modern

Nadia, standing next to Reborn sounds of childhood dreams by Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi, wants people to feel "that the art is something they can claim"

- Published

Nadia Denton wants you to think differently about African art.

"There's this misconception that African art is solely about masks or sculptural types," says the volunteer African heritage tour guide at the Tate Modern art gallery in central London.

"The work we generally look at on the tour doesn't look 'African'."

Inside the gallery, Nadia's vision immediately becomes clear: the pieces she focuses on are modern, conceptual, abstract, and entirely at odds with the cliches of African art many visitors expect.

On bare white walls, bursts of colour spill out from modern canvases. Textiles hang in layered sheets, bold shapes stretch across the room and sculpture silhouettes rise in unusual forms.

Nadia runs various tours across several museums.

At the V&A, she leads the African Gaze, looking at portrayals of African people in 17th and 18th Century European art. At the British Museum, she explores the Nigerian Igbo worldview.

But here at Tate Modern, her focus is African Modernism and Afro-Surrealism - movements she says are rarely spotlighted in major Western galleries.

"Artists of African descent have often been maligned, or faced difficulty in getting visibility in the wider international industry," she says.

Nadia tells the group on the tour that her aim is to bring attention to the artists' work in a way that feels accessible to anyone.

"It's really about presence," she adds. "Being warm and friendly. Not speaking above people's heads. Using everyday examples. I want people to feel that the art is something they can claim."

The group discusses Malian artist Abdoulaye Konaté's piece, Intolerance, during the tour

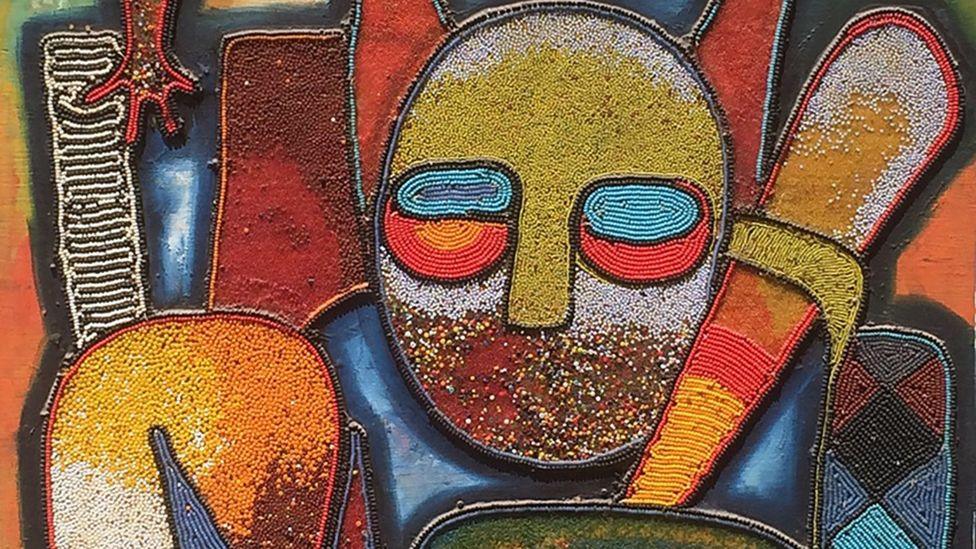

During our tour, the group stops in front of Intolerance, a piece by Malian artist Abdoulaye Konaté.

Stitched from colourful textiles, flip-flops, bullet shells, notebook paper and other found materials, the work forms an abstract scene of a figure lying on the ground.

Nadia explains these textures and objects speak to the fractures that emerge when communities turn against one another. She asks the group how it makes them feel, and the moment becomes a shared interpretation.

African American artist Simone Leigh's work Sentinel merges the female form with the architecture of a dwelling or protective space

Next is a glossy black sculpture of a woman, her head rising from the top of a large, rounded form. Nadia asks the group what they think it looks like.

"A tunnel," says one.

"A bomb shelter," says another.

Nadia nods encouragingly and introduces the work as Sentinel by African American artist Simone Leigh, who says the work merges the female form with the architecture of a dwelling or protective space, creating figures that are part body, part home.

She adds the forms are rooted in black feminist ideas around the female body.

"They're majestic, intimidating and powerful," says Nadia.

Challenging colonial legacy

Nadia's tour is part of a wider shift taking place across museums in the UK.

Tate Modern is currently running a sell-out exhibition on Nigerian modernism which reflects a growing appetite for work overlooked in major institutions.

Nadia openly acknowledges the colonial histories tied to many objects in UK museums, including those taken or looted during the British Empire.

"Just by being in front of an artwork or speaking to it we can bring life to it," she says.

"We can change how that object is perceived and have some impact on its future legacy."

Nadia's aim is to create a new "voyage of discovery" with her audience

She explains how colonial history has shaped what African artworks have been preserved and displayed.

Nadia says her role channels the essence of a female "griot" – a traditional west African storyteller. Her aim is to create a new "voyage of discovery" with her audience.

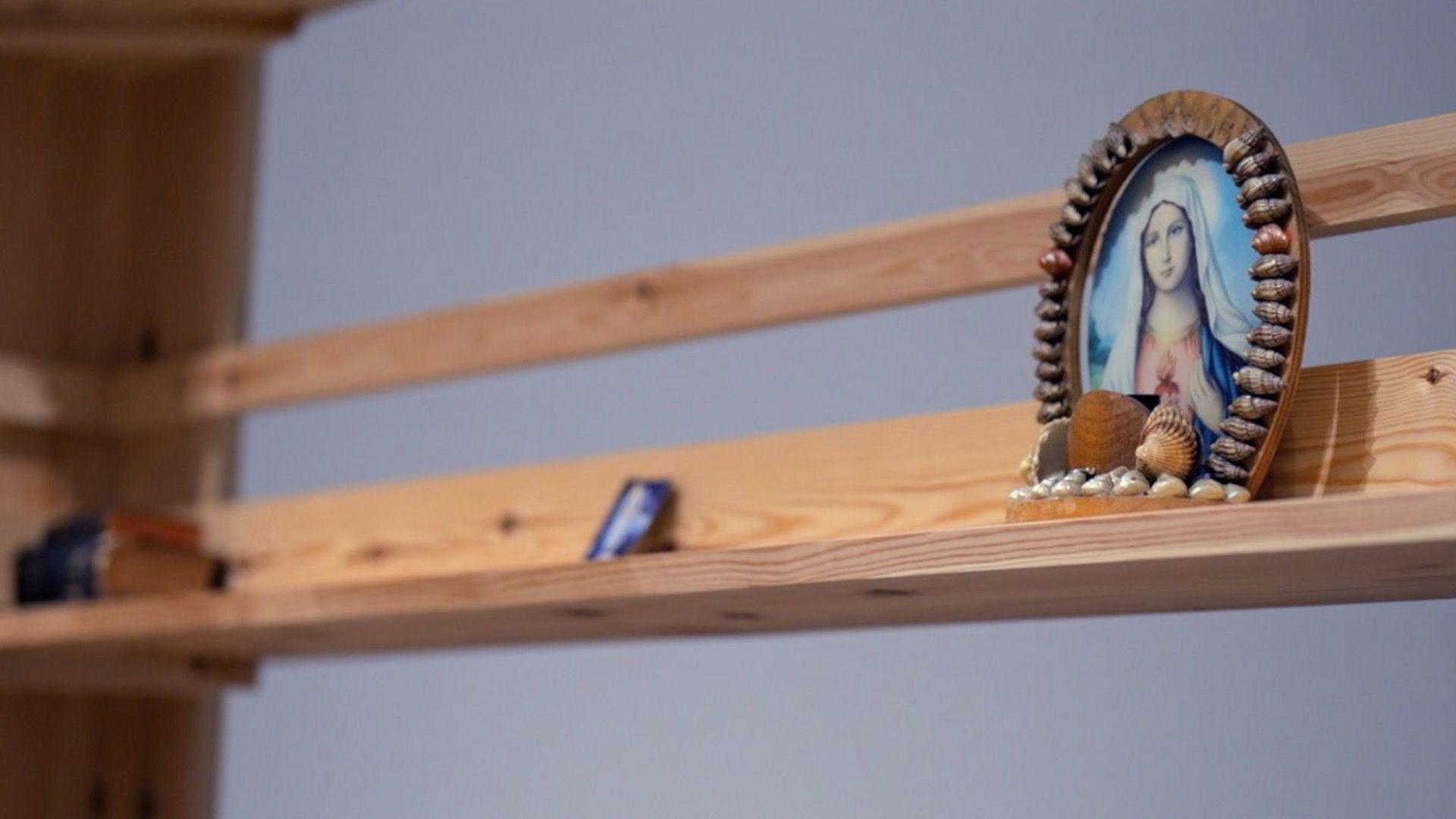

At the final stop, we reach Beninese artist Meschac Gaba's Museum of Contemporary African Art.

The group steps inside a cross-shaped wooden structure filled with more than 75 objects linked to different world religions and cultures.

The space is part installation, part archive.

Meschac Gaba's Museum of Contemporary African Art challenges the idea that African art is limited to masks and sculptures, says Nadia

Nadia explains how Gaba challenges the idea that African art is limited to masks and sculptures by bringing together symbols from Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Vodún and other traditional African faiths.

Nadia says she measures the impact of her own work in simple terms, including how visitors respond.

"If they're still with me at the very end," she says, "I know I've done a good job."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

More stories about art in London

- Published30 November 2025

- Published8 October 2025

- Published29 November 2025