| You are in: Americas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

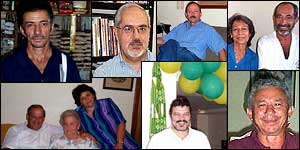

| Friday, 4 October, 2002, 11:48 GMT 12:48 UK Voters' voices: The Brasils of Brazil  'Brasil' is widely used in names in Brazil As Brazil prepares for presidential elections on 6 October, the BBC's Isabel Murray asked nine people named "Brasil" how they feel about the future of their nation and namesake. Click on the links to read what they said S�crates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira, 48 - known simply as S�crates - is a former captain of the Brazilian football team, a sports commentator and a qualified doctor. He says he is fond of the 'Brasil' part of his name. "I am totally committed to this nation. It's the only place in the world where I can enjoy life," he says.

But he says that the relatively poor uneducated Brazilian population is easily manipulated. "We have an endless capacity to produce more wealth, to distribute wealth, to allow the population access to all the basic requirements of civilisation. "But it is very obvious that there is an elite which is working towards the opposite objective. "However, there is such a backlash from the oppressed population that sooner or later this is going to have to change." He is also critical when it comes to football: "The Brazilian football administration is riddled with corruption and full of incompetence," he says. Brasil do Pinhal Pereira Salom�o, 60, is the founding partner of one of the largest law firms in the interior of the state of S�o Paulo. He oversees a team of 45 lawyers and 46 trainees, has been married for 35 years and has two children.

"I believe very strongly in this country, and I have a lot of hope for the new Brazil, after the October elections, when in all likelihood we will bury neo-liberalism," he says. "I feel that the first two years will still be difficult because of the damage that the economy has suffered. "But due to the country's natural vigour and wealth, and because of the Brazilian people, who like peace and work, I am hopeful for Brazil's future," he says. For him, Brazil's racial integration is a cause for optimism: "I am the grandson of immigrants, and I live with immigrants of all races. I believe that this country could be the foundation of a globalised nation with races transformed into a single people and nation." Brasil Fernandes, 44, owns a small store in the borough of Anchieta, Porto Alegre, in a shantytown area which taxi-drivers prefer to avoid. He lives with his wife and nine-year-old daughter in the back part of the shop building.

Educated to fifth grade, and fearful that the land his shop is built on will be repossessed, Brasil Fernandes is pessimistic about the country's future. "The way Brazil has been going things aren't likely to get better, but instead to get worse. We are hoping for a president who will do what is best for the people," he says. He says business is slow at his shop at the moment. "I hope that the future of Brazil brings more hope," he adds as he serves a beer to one of his few customers. Dona Bras�lia It�lia Cirilo da Silva, 83, is a retired civil servant. She lives in a middle-class area in the city of Porto Alegre, and receives a pension following her husband's death.

"I think the future is very uncertain. I no longer have any faith in the politicians. There is so much corruption it frightens me," she says. "I remember when politicians were honest." The name Brasil has been passed on to two of her children. Brasilio Ricardo Cirilo da Silva, a retired civil servant and academic, is also pessimistic: "In the past we had strong leaders. Nowadays you can't even point to one or two leaders who have nationwide influence. I am unable to see anything good further down the road," says Bras�lio. And Brasilia It�lia Cirilo da Silva Ache, a doctor and academic, says the gap between rich and poor is growing. "The middle classes, the professionals, who used to enjoy a better life in this country, are also being crushed under foot," she adds. "You have to have hope and believe that things are going to get better, because they just can't get any worse," she says. Lael Vital Brazil, 71, is a retired airline pilot and lives in Rio de Janeiro. He is the 17th child of the scientist Vital Brazil, who developed snake-bite serum and founded two of Brazil's most important scientific research institutes.

"Nowadays in Brazil we do not have a health policy, but rather a sickness policy," he says "Our hospitals do not function well. Rio and Sao Paulo both suffer from poor sewage facilities and also low-quality the water, which leads to a huge burden on the hospitals". But he still holds out hope for the future. "I believe that here in Brazil we have well-intentioned people and intelligent politicians. "I have no doubt that bit by bit these people will come to the forefront and bring with them a faster rate of development," he says. Luis Antonio de Assis Brasil, 56, is a renowned writer and academic with 15 books to his name.

He says the name Assis Brasil dates back to Irish migrants who travelled to the then Portuguese-owned Azores Archipelago, from where their descendents moved to southern Brazil. But, he says, the name's roots date back ever further - "Hy Brazil" meant "blessed land" in Celtic, and was said to refer to an island discovered by St Brandon who lived in the 6th Century. "We are in between two models. The dominant model is the neo-liberal, globalised one, and the other model is one which is opposed to all this," he says. "If we had a parliamentary system of government, we might be able to get a government where these two forces could work in harmony. "But as we have a presidential system - which is a really big problem that has already caused a great deal of harm - we have to live with this dichotomy," he says. "People need to feel safe in their lives and the government should not have as overwhelming a presence as it does at present. "There are already countries that live like this, but I think it will take Brazil a bit longer to get there. People of my generation are not going to see it come about," he says. Jos� Freire Brasilino, 59, is a farmer and military reservist. He is married with three children and his time is split between his farm on the island of Maranh�o and an apartment in Recife, state capital of Pernambuco.

You almost end up not believing in the future of this country. "I was in the army for 33 years and I saw patriotism close-up. It appears that Brazilians have forgotten what patriotism is. You no longer see people in the schools singing the national anthem. In my day, the notebooks we used to have came with the lyrics of the national anthem printed in them. "That is why people no longer value life. One person murders another over a pair of expensive training shoes. "But Brazil is still a very good country to live in. Maybe even our children won't see Brazil become a unified country. That will be up to our grandchildren," he says. Jo�o Pedreira Brasil, 59, is a retired economist living in an elegant neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro.

A local pharmacist offered him a free place at the school his wife ran. But the benefactor, unimpressed with the boy's humble name, drew inspiration from a map of Brazil on the wall at the time and christened him Jo�o de Oliveira Brasil. "I am very optimistic. Brazil has already declared a debt moratorium and it's already been in embarrassing situations... But now it is finally beginning to realise that it can't spend more than it gets," he says. "Brazil has already got better over the last 20 years. We can make things even better, with this new political awareness that is taking shape and improving social justice, the country's future is a bright one. We have a lot of potential." Brasil Ferreira da Silva, 67, retired 10 years ago from his work in the Rio de Janeiro state Security Department. He lives in the north of the city, not far from his sister, Bras�lia Ferreira da Silva, 66.

"When [the Formula One driver] Ayrton Senna was still around, Brazil was better - nowadays, there's no more fun," says Brasil. "If we had different candidates maybe I would have some hope of change. But the candidates are the same ones as always and nothing is going to change. The poor are getting poorer, and the rich are getting richer." |

See also: 20 Aug 02 | Americas 19 Jul 02 | Americas Internet links: The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites Top Americas stories now: Links to more Americas stories are at the foot of the page. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Links to more Americas stories |

| ||

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To BBC Sport>> | To BBC Weather>> | To BBC World Service>> ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- © MMIII | News Sources | Privacy |