Creativity, ingenuity and global triumph

The global video games industry is estimated to be worth £110bn. While America and Japan dominate the market, the UK video games sector directly employs over 20,000 people, and is estimated to be worth £3.86bn.

From a handful of hobbyists coding in their spare time to big teams, big budgets and million dollar profits, the story of British video games is one of fantastical imagination, irreverent humour and the coding skills of some standout personalities.

February 1975

Games Workshop – Bringing fantasy worlds to British tabletops

The story of British video games can be traced back to humble beginnings some 40 years ago.

Keen gamers Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson founded Games Workshop to make and sell wooden board games, and bring the latest games news to like-minded Britons. JRR Tolkien’s novels had spawned the fantasy genre, and business grew after the pair introduced an American role-playing fantasy game, Dungeons & Dragons. The game transported players to open-ended worlds to invent stories and solve puzzles, stirring the imagination of future British video games makers.

Ian Livingstone revisits the site of his first Games Workshop store and shows the interactive worlds he created in his Fighting Fantasy gamebooks.

Games Workshop – Bringing fantasy worlds to British tabletops

Video transcript

IAN LIVINGSTONE:

Forty years ago, I helped to create a company that changed the way British people play games. It also provided an unexpected catalyst for the digital phenomenon. Steve Jackson and I set up Games Workshop in 1975 – a company that would bring a brandnew game to the UK.

Dungeons & Dragons was unlike any other game. It had no board, no fixed rules and no end!

One player – the Dungeon Master – dreamt up their own elaborate story set in a fantasy land. Friends got together and used their imaginations to play out their characters’ lives with tabletop figures. At every turn of the story, they’d roll dice to determine their outcome.

Dungeons & Dragons enjoyed phenomenal popularity based on little more than word of mouth recommendations. Steve and I put on a huge Games Day conventions. Thousands of people gathered in halls to play D&D.

And it wasn’t just board games that were totally re-imagined.

Steve Jackson and I wrote a series of game books, these were not just a passive experience for the reader – these were books in which YOU were the hero who chose your own way through the books.

VOICE OF BOY:

Turn to page 90, draw your sword and fight them!

IAN LIVINGSTONE:

Collecting items and risking your character’s health in battle all added to the excitement. Many of the techniques found in these game books became commonplace in future computer games.

This was the beginning of interactive gaming. So when the home computing revolution began, a few clever Brits were well placed to take these ideas and digitise them… giving birth to Britain’s first interactive video games.

Autumn 1978

MUD – University students create the first computerised role-playing game

Meanwhile British engineers were leading the development of electronic computers. Some of the first software for the early machines were simple games.

Inspired by Dungeons & Dragons, Essex University students Richard Bartle and Roy Trubshaw created MUD (Multi-User Dungeon) – a text-based adventure game in which players typed short commands to travel through a fantasy world. They found a way to exploit the memory of their huge mainframe computer so that several people could play together across the university network. The game’s popularity quickly spread as they shared it freely, encouraging other hobbyists to create their own versions.

MUD inventor Richard Bartle on how the huge popularity of role-playing video games today can be traced back to MUD (from Games Britannia, BBC Four).

September 1983

Manic Miner – Quirky bedroom creation becomes a home computer classic

Britain’s computing pedigree saw the release of home computers like the ZX Spectrum, which kickstarted a boom in the development of new software.

These computers were easy to program; 17-year-old Matthew Smith was loaned a Spectrum and in just six weeks wrote Manic Miner, a quirky, irreverent game that appealed to the British sense of humour. Players had to guide Willy – a miner – through caverns to collect flashing objects, avoiding poisonous pansies and other deadly traps. Pushing this early 8-bit computer’s capabilities to its limits, Manic Miner’s imaginative music, colourful graphics and enticing playability had the public hooked.

Why is Manic Miner one of the most quintessentially British 1980s games? (from Games Britannia, BBC Four).

Manic Miner – Quirky bedroom creation becomes a home computer classic

Video transcript: clip from Games Britannia, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC Four on 21 Dec 2009

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

There couldn't be a better example than this: Manic Miner. It looks horrible and sounds dreadful.

You’re a miner exploring a series of excavated coal scenes, picking up treasure whilst avoiding a plethora of ever more surreal moving objects.

CHARLIE BROOKER:

It was a really basic game, but it had a weird, Pythonesque sense of humour to it, which is a very British thing. And a lot of those early British games did. When you died, you’d get sort of squashed by a Pythonesque foot - would descend from the heavens and crush you. I think that was what appealed to me, the weird humour of it.

September 1984

Elite – Revolutionary 3D space adventure sets new standards

By 1984 British home computer sales were reportedly the highest in the world. And two Cambridge students created one of the biggest hits of the year.

Experimenting on the BBC Micro, David Braben and Ian Bell wrote space trading game Elite in their spare time, just before their finals. Players journeyed across galaxies trading, defending and upgrading their spaceships. With just 22KB, Elite’s innovative 3D image outlines and open-ended gameplay rewrote the rules of video gaming. It also became the first non-American game to become a US bestseller.

See the early sketches for Elite and watch the pioneering gameplay in action (from Games Britannia, BBC Four).

Elite – Revolutionary 3D space adventure sets new standards

Video transcript: clip from Games Britannia, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC Four on 21 Dec 2009

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

I’ve come to Queen Mary's College in London to meet two of the original bedroom coders, Ian Bell and David Braben, architects of one of the most important British video-games ever made – Elite.

And these were the blueprints, just doodlings in a ring-binder. They may not look much, but in terms of the history of video games, they are like Leonardo's sketchbooks.

Look at this. This is an early design for the screen- is that right?

IAN BELL:

Yeah that’s, I think, the first doodled design of what we thought the game might look like. It was the first game that put the player in 3D, that sort of taught the player how to move and think and navigate in 3D. Sort of raised the bar, in terms of ambitions for games.

DAVID BRABEN:

We expected you to take weeks to finish the game, not minutes. There was no score. There were no lives. And these were all the mantras, these were all the mechanics. We were just breaking rules, one after the other after the other. The original concept is sort of 3D ships fighting each other, but we just decided that would be too empty, too hollow an experience. There wouldn't be enough reason to want to continue.

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

The objectives of the game are basically simple. You were a trader, flying through space, buying and selling goods.

DAVID BRABEN:

Thatcher was in government, so I though “Well, OK, it has to be money, doesn't it?” And the idea that you spend your money on other things to improve your spaceship.

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

But you were not alone in this world.

To get to the top and reach Elite status, you have to destroy space pirates, aliens, and sometimes even the police. To stand any chance of survival in this universe, I’ll need help.

So I have recruited economist and Elite enthusiast Tim Miller to guide me through the game. Despite the Etch-o-Sketch graphics and sound effects that a Casio watch would put to shame, the excitement at engaging in a bit of cosmic destruction is overwhelming.

It is exploding, a great cloud of particles.

Having dispatched some space pirates, our way is now clear to the space station and another integral part of the game.

Welcome to the world of intergalactic trading, as important as space combat in Elite.

Having set our sights on the agricultural planet Sutiku, I am wondering if it’s worth trying to sell them computers. But then it occurs to us that what would make an absolute killing would be to take these farmers some illicit goods.

Let's pack some heat. Let's take…There we go, 23 tons of firearms. That’ll warm things up.

Let's see what happens when we do that. So, we've done it. Now, what will the consequences be?

TIM MILLER:

Well, the consequences will be that when you choose which planet to go to, ehm, and we take off…

And we are in hyperspace there. The police will take an interest in us. And more's the point, the police are going for us at the moment. You can see there is a blue spot on the radar.

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Suddenly, an innocent cargo hold full of computers is looking like a wiser move. The rozzers are all over us because of our choice to carry guns. Who would have seen that coming!

TIM MILLER:

I think we might be out of luck here.

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Because we are running too low on energy? Oh, game over!

MUSIC LYRICS:

I fought the law and the law won

I fought the law and the. . .

June 1987

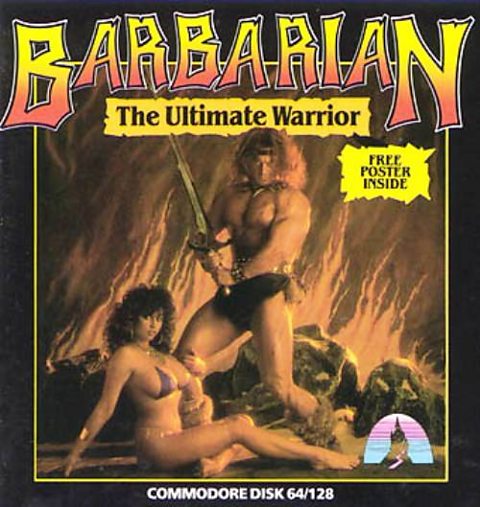

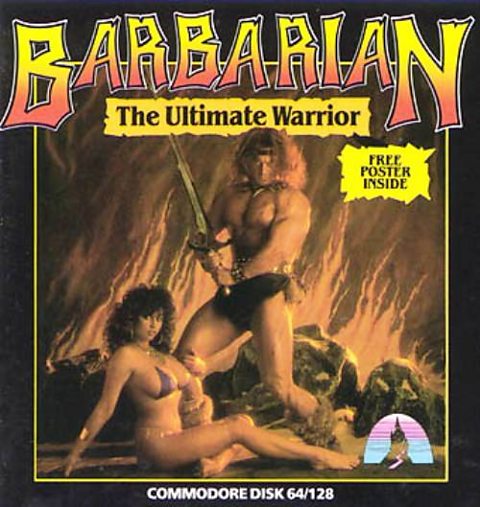

Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior – Video games target an adult market

Not all British video games received universal acclaim. In 1987 London-based Palace Software released a game that caused a storm in the UK and abroad.

Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior had players fighting gory battles on the Commodore 64 computer. It sparked public protest in Britain over its violent content and the use of a bikini-clad Page 3 girl in its marketing. In Germany, its sale to under-18s was initially banned. The media controversy only boosted the game’s popularity. Video games were no longer just child’s play, they were a lucrative form of adult entertainment too.

June 1989

Populous – The first game that lets you play ‘god’

British game makers used the increasing processing power of home computers to create innovative new formats.

British video games pioneer, Peter Molyneux, wanted to make something intellectually challenging. He devised Populous – the first ever ‘god’ game. Players took on the power and responsibility of a deity, making moral choices to shape landscapes, inflict disasters and gain civilian followers. Populous sold over four million copies and created a genre that would encompass other big sellers, notably The Sims, and further open up the games market by appealing to women as well as men.

Peter Molyneux on how god-game Populous, and its follow-up Black & White, gave players both power and responsibility (from Games Britannia, BBC Four).

Populous – The first game that lets you play ‘god’

Video transcript: clip from Games Britannia, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC Four on 21 Dec 2009

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Populous had broken the mould by giving players a taste of ultimate power, but also responsibility.

Both Populous and its offspring Black White offered a new realm in which you could play with a living, breathing world. It became known as the God Game because, as in a board game, the player has god-like powers to move the pieces and choose their fate.

VOICE FROM GAME:

Are you a blessing or a curse? Good or evil? Be what you will, you are destiny.

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

The godfather of the ‘god’ Game is Peter Molyneux, one of the most influential games designers of our age and an indefatigable evangelist of the potential of computer games.

So, this is Black & White. You have got an incredibly rich environment here.

PETER MOLYNEUX:

Much richer isn’t it than the original Populous isn’t it. But there are similarities. You know, look at the view that we are looking down on. It is not too dissimilar. We can still see villages, we can still see little people moving around. OK, there is a big creature now. Ehm but we have got this little… We’ve got this… in Populous, this little hand, in Black & White, we’ve got a big hand, and you could…

You know I really wanted to give the feeling that you could reach down into that world and pluck someone out. You can throw rocks and squash people and you can save people from drowning, and you can… In Black & White, famously, you could say, you two are going to get married.

February 1991

Lemmings – Innovative computer puzzle tastes global success

In Dundee, a group of friends from an amateur computer club founded what would become one of the world’s most influential video games companies.

DMA Design’s first global hit was Lemmings. Directing a group of lovable, green-haired humanoid lemmings through obstacles at increasing levels of difficulty, this was their take on popular arcade platform games originating from Japan. It was initially released for the Amiga computer, exploiting its split screen capability and dual mouse inputs in the two-player levels. Lemmings sold 55,000 copies on its first day of release, and versions were soon released for other computers and game consoles.

BBC Reporting Scotland in 1994 announces Nintendo’s commission of DMA to develop its latest video games on the back of its Lemmings success.

Lemmings – Innovative computer puzzle tastes global success

Video transcript: clip from Reporting Scotland, first broadcast on 3 May 1994

JACKIE BIRD (NEWS ANCHOR):

The computer games giant Nintendo has commissioned a Scottish company to develop the games for their latest generation of home computer.

And the contract could mean millions of pounds and new jobs for Dundee, as Neil Mudie reports.

NEIL MUDIE:

The computer game Lemmings guaranteed the success of DMA Design. Times are already pretty good, as the matching Mercedes in the car park testify.

But even for such a prosperous company, the Nintendo deal is the big one.

DAVID JONES:

I think it is, yes. With Nintendo behind the actual sales of the game – Nintendo have a huge worldwide market. And especially being a new system, which most people are quite excited about, then I would say it would probably be bigger than the actual Lemmings game, yes.

NEIL MUDIE:

The success of DMA lies in the fact that all their young designers don’t just have brains, they have a sense of fun and enjoy playing the games they create.

David Jones who established the company with redundancy money from Timex, about six years ago, still gets a kick out of Lemmings.

Nintendo have likened him to the Steven Spielberg of computer games. And intend to launch their new products on the American market in around 12 months’ time.

The company will share the copyright on any games with Nintendo. And so, should they produce a worldwide hit such as Super Mario or Street Fighter 2, the earning potential could run into tens of millions of pounds.

Neil Mudie, Reporting Scotland, Dundee.

September 1995

WipE’out” – 3D anti-gravity racer helps launch PlayStation console

Power came to the console in 1995, with the new 32-bit Sony PlayStation. Gaming had finally left its roots behind and entered the corporate world.

Unlike its 8-bit and 16-bit predecessors, the PlayStation had 3D graphics and a CD-ROM with revolutionary audio and visuals. Sony turned to a British developer, Liverpool based Psygnosis, to show off its high spec. It created a futuristic driving game Wipeout. With a techno soundtrack and stunning visualisations, Wipeout appealed to the clubbing generation and brought a cool, slick image to video games. It became the PlayStation’s best-selling launch title in Europe.

Benjamin Woolley looks at the alluring elegance of WipE’out”, and why its appeal still endures today – nearly two decades after its first release.

WipE’out” – 3D anti-gravity racer helps launch PlayStation console

Video transcript: clip from Games Britannia, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC Four on 21 Dec 2009

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Oddly, the game that more than any other established the street credibility of virtual games Britannia, was one involving vehicles floating several feet off the ground.

Launched in 1995, Wipeout was a futuristic racing game that immersed the player in an intense context of speed and combat. It was set in the year 2052 and you had to see how high you could get in the F3600 Anti-Gravity Racing League.

Set in a soaring, stunning urban location, Wipeout proved to be a huge international hit, racing to the top of the UK as well as US charts. And it's proved to be fantastically durable, at least by video-game standards. It's still being played today, a decade and a half after its release.

Like the original, the new version is a sinuous, interweaving of flowing fluorescent racetracks and rhythmic, hypnotic dance tracks.

It's a captivating, almost giddy experience. The races only last a few minutes, but each time you're enticed back, not just to improve your performance, but to experience once again the sublime elegance of the race itself.

August 1997

GoldenEye 007 – James Bond turns video games cinematic

Two years later, a more powerful console was released – the Nintendo 64. Again, the manufacturers turned to British talent to showcase its power.

In a converted farmhouse in rural Leicestershire, developers Rare created GoldenEye 007, based on the Bond film. It took over two years to create, pioneering a more realistic style than games before it, with use of stealth and multiplayer gameplay. Its immersive, cinematic experience set the game apart. GoldenEye grossed $250m and won the first ever BAFTA Interactive Entertainment Award, a recognition by the British entertainment establishment of the increasing importance of video games.

October 1997

Grand Theft Auto – A world dominating game series is born

Following the success of Lemmings, Dundee studio DMA Design achieved another hit in 1997 with Grand Theft Auto for the PC and PlayStation.

Influenced by early games such as Elite, this open-world action-adventure saw players assuming the role of a criminal roaming freely around three fictional cities, able to go wherever they chose and do whatever they decided. Although the 2D, top-down graphics were considered somewhat limited, the game was praised for its sound quality, fun factor and playability. With over two million units sold, however, it was only a foreshadow of the global dominance that the franchise would later achieve.

Rory Cellan-Jones visits the DMA studio in 1996 as they develop a new game – Grand Theft Auto.

Grand Theft Auto – A world dominating game series is born

Video transcript: clip from Working Lunch, first broadcast on 16 May 1996

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

This may not look like the offices of a major computer company. It doesn’t really look like anybody’s office does it?

But it is in fact the relaxation area of a very relaxed company. And ehm they are in their lunch hour so they are allowed a bit of spare time.

Ehm this is DMA Design in Dundee. They make computer games. They were only started in 1987 by somebody made redundant from Timex up the road.

And they have grown very rapidly in the last couple of years on the back of the success of a game called Lemmings. They are now working hard on a whole lot of other games. They’ve got over 100 people here. They are talking about opening up in America.

Let’s have a look at what goes on behind these screens.

Now all the people in here are working on what DMA hope will be its new blockbuster. It’s a game called Grand Theft Auto. It’s got to be finished by the end of June so it – so they’re involved in some hard work in here.

It’s all about a car chase through the streets of a fictional, probably American, city. Here are some of the maps they’ve been working on.

And Dave here is one of the software designers that’s been trying to put it together. Dave just explain the point of the game.

DAVE (SOFTWARE DESIGNER):

Ehm well it’s a mission based driving game where you’re basically driving around a city, stealing cars, running over pedestrians and…

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Pretty tame stuff then.

DAVE (SOFTWARE DESIGNER):

Well eh… staying away from emergency services, police and that sort of thing. Driving in traffic.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Oh, you’ve just got out of the car.

DAVE (SOFTWARE DESIGNER):

Indeed, well we can go and we can take any car we want.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Right you’ve just stolen a car, fine.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

What’s your job then? What are you doing here?

DAVE (SOFTWARE DESIGNER):

Well I’ve been doing the basic car movement and also the dummy pedestrians and the object reactions. And basically it’s just getting the cars to look good and run fast, and having the people wandering about and making them look like a real crowd in the city streets.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

You’re coming up against a deadline now. What’s the working pattern here like?

DAVE (SOFTWARE DESIGNER):

Ehm, well when we need to we work late, very late sometimes. We’ve had a couple of allnighters to hit other deadlines that we’ve had during the game. And eh…

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Well we’ll let you get on with it and see what else they are doing elsewhere in the plant. Now this is DMA’s music department. As you can see they do use real instruments here. Let’s find out what they’ve been doing for the Grand Theft Auto Project.

Craig, what have you been contributing?

CRAIG (MUSIC DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE):

Ehm I’m working on a radio station at the moment, the hip hop station. There’s a variety of different stations in each car that you go into.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Every time you get into a car you get different music?

CRAIG (MUSIC DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE):

Yeah, different station. So this is a hip hop channel that we’re in the middle of doing just now.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

So you’ve not just taken it all off a CD you’ve actually composed it?

CRAIG (MUSIC DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE):

No, no everything’s composed in-house, yeah.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Amazing amount of work. We’ll let you get on with it.

CRAIG (MUSIC DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE):

Right, OK.

January 2001

Runescape – PC games revival as broadband connects gamers worldwide

The growth of broadband internet in the early 21st Century helped kickstart a new era of social gaming.

The multiplayer MUD game dreamed up by students in 1978 had become a new genre – the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). Runescape was a web browser MMORPG made by Cambridge University student Andrew Gower with his brothers, who together founded Jagex Games Studio. Entering a fantasy world via an avatar, players interacted with each other by trading, fighting and cooperating on tasks. Runescape became the world’s largest free MMORPG, with 237 million users by early 2015.

What do the virtual worlds created in Runescape reveal about the players themselves? (from Thinking Allowed, Radio 4).

Runescape – PC games revival as broadband connects gamers worldwide

Video transcript: audio clip from Thinking Allowed: Lost in Runescape – Social Worth in Early Modern England, first broadcast on Radio 4 on 7 Mar 2007

Video clip courtesy of Jagex Games Studio

LAURIE TAYLOR:

What I want to ask you about, Simon, is when we examine the worlds which the players of this game construct, what do we notice?Because to some extent they can create their own norms, their own values, their own system of justice… What can we read off from the worlds they create about their own lives?

DR SIMON BRADFORD:

I think it’s very difficult to read off in a kind of simple way. But I think that certainly we’ve become aware over the four or five years that we’ve been doing this work, that there’s a great tradition in Runescape of kind of collaborative enterprise amongst young people. And certainly we’ve had emails from young gamers who have wanted to point out the extent to which Runescape is indeed a collaborative world.

And I think there is a great deal interest beyond Runescape in using these sorts of gaming experiences as means of looking at young people’s skills and so on.

LAURIE TAYLOR:

Because when they are working certain skills cooperation is necessary.

DR SIMON BRADFORD:

Yeah, yeah that’s exactly right. That’s exactly right.

LAURIE TAYLOR:

I suppose for example something like shark fishing you can hardly do that by yourself.

June 2001

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider – Video game heroine becomes a global moviestar

Tomb Raider was the action-adventure game that introduced the world to fictional archaeologist Lara Croft – and in 2001, she went to Hollywood.

As one of the first ever female game protagonists, Lara’s launch in 1996 had already caused a media sensation. Her image had graced the cover of lifestyle magazines and TV adverts, from Land Rover to Lucozade. When Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, starring Angelina Jolie, was released, it topped the box office chart. But the British companies that developed this valuable franchise failed to hang onto it – Tomb Raider was later sold to Japanese publisher Square Enix, and development moved to the US.

Ian Livingstone reflects on how he helped to launch Lara Croft to the world and reveals the cultural, commercial and global phenomenon she became.

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider – Video game heroine becomes a global moviestar

Video transcript

IAN LIVINGSTONE:

2001 was the year that British video games hit Hollywood. We released the first Tomb Raider back in 1996. The original idea was to have the main character as a man. But the design team felt a heroine would be better suited for the game’s puzzle-solving elements.So Lara Cruz was born; as she was originally known. Her name was changed, of course, to Lara Croft – to make her sound typically English.

Nobody really knew how gamers were going to react to her. Some saw Lara as an object of male desire. But to others she represented female empowerment – because she was independent, clever and strong.

We discovered about half of Tomb Raider’s players were female.

And that first game sold a staggering 8 million copies.

Since then, there have been 11 more Tomb Raider titles. The games have brought in more than one billion dollars in revenue – something we’d never have dreamt of when we first developed the game.

But Tomb Raider – the brand – took on a life far beyond its video games roots.

Lara Croft’s image began to grace magazine covers alongside A-list celebrities. Lucozade changed its name to Larazade for 3 months, and saw a significant spike in sales. The huge buzz around Lara attracted the attention of some really big players.

After negotiation, we licenced Lara Croft to Paramount Pictures. And in 2001 – Lara Croft: Tomb Raider was released starring Angelina Jolie.

It was an instant box office hit, grossing 274 million dollars in its opening weekend alone. Here was a video game that started life as a simple sketch and became a valuable intellectual property in its own right.

A game crafted by a handful of creative Brits in a small studio in the East Midlands, had become a global phenomenon.

Today, much of the revenue generated by Tomb Raider travels overseas. The franchise was bought by a Japanese company in 2009 and the game is now made in the States.

But at the time, it proved what an enormous commercial and cultural punch a British video game could pack.

Lara Cruz concept sketches courtesy of Core Design / Eidos Interactive (now Square Enix)

April 2008

Moshi Monsters – Online children’s game enthrals millions

Video game brands kept spreading through popular culture, especially with a young audience who had grown up in this new, always connected, world.

London-based Mind Candy launched Moshi Monsters as a website in 2008. The game allowed children to adopt a pet monster, solve educational puzzles and socialise with other children. By 2013, a staggering 80 million were playing the game worldwide. Moshi Monsters were featured in a wide range of merchandise, from books and bath soap to McDonald’s Happy Meal toys, and even had their own feature film.

Peter Jones meets Michael Acton Smith at Mind Candy's playful offices to see Moshi Monsters in action (from Peter Jones Meets, BBC Two).

Moshi Monsters – Online children’s game enthrals millions

Video transcript: clip from Peter Jones Meets…, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC

Two on 16 Jun 2013

PETER JONES:

39-year-old Michael Acton Smith is an energetic and creative entrepreneur.

MIND CANDY PRESENTER:

We've got your letters! We've got ink! We've got live music from the tree house!

PETER JONES:

Mind Candy, Michael's web-based entertainment business and parent company of the online phenomenon Moshi Monsters, has been an incredible multi-million-pound success.Its home is here in Shoreditch, the London location for media and creative business with a digital twist.

Michael! Great to meet you.

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

Great to meet you, too. Welcome to our HQ.

PETER JONES:

Wow, what a place!

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

We have a treehouse, we have vines, we have toys aplenty.

PETER JONES:

With all these temptations to play, I wondered how Michael persuaded his staff to do any work.

But I was also trying to decide what this playful office said about his approach to business.

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

Business is often seen as grey and boring, but I think business is almost like this eh canvas that you can paint on. You can take ideas in your head and put them out on the marketplace.

And I personally just think that's incredibly exciting.

PETER JONES:

Michael's online game and social network for children has 72 million users in 196 territories worldwide. But what is a Moshi Monster? Shall we have a little game?

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

Yeah, shall we have a look? I've got a monster called Snowcrash. I can get him to walk around the room by clicking on the floor. I can tickle him here and he'll giggle away. It's difficult to imagine me being a six-year-old kid, but…

PETER JONES:

If I was a six-year-old Peter Jones, what would I find exciting about a fluffy monster?

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

Well, we've created a world where children can adopt their own monster, and they are in charge.

They can feed it, they can play games with it, they do educational puzzles. And then there's a whole social side, where they can safely chat to their friends, they can send each other messages, they can share their artwork.

PETER JONES:

And then so how does it work, income-wise, for you? Is it free at the moment?

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

Yes, most of the children that sign up play for free. And then they can get a Moshi Monsters passport. Parents can pay about 5 pounds a month to access new parts of the world, to play new puzzles and games and buy new items and so forth. And that's one part of it. The second part is the physical merchandise that we've created.

There's a magazine, there are puzzle books, toys…

PETER JONES:

You're sort of targeting children to get them engaged, but at the same time I'm assuming your target market is also parents, because kids go up to their mum and dad, as mine do to me, and say, "Dad, can I have 10 pounds for this?" Or, "Can I go online with that?"

MICHAEL ACTON SMITH:

It's a really interesting challenge, so we have to make the experience of Moshi fun for kids, so they fall in love with it and they're engaged and they share it with their friends, but we need to make sure parents feel comfortable with it, too, that there's some kind of educational value to it, which there is. So we decided to make something that was fun, first and foremost, with education woven in underneath. We call it stealth education.

PETER JONES:

Clearly, Michael's canny. He's not simply selling his game to kids, he's persuaded their parents to part with their money and turned his game into a playground phenomenon.

November 2008

LittleBigPlanet – Connected consoles allow bedroom gamers to create

Games consoles were also becoming connected, driving further innovation in community gaming and reaching wide audiences.

Media Molecule’s puzzle-platformer LittleBigPlanet first launched for the PlayStation 3. The game was acclaimed for its beautiful visuals and social gameplay. Not only could users play together through the PlayStation Network online gaming service, they were also encouraged to create their own levels and publish them for others to explore. By 2012, 8.5 million copies of the game series had been sold, and over seven million community-made levels developed.

What sets ‘the Facebook of video games’ apart (from Games Britannia, BBC Four).

LittleBigPlanet – Connected consoles allow bedroom gamers to create

Video transcript: clip from Games Britannia, Episode 3, first broadcast on BBC Four on 21 Dec 2009

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Today, we're all living in a global village.

Part of a rich, diverse, human family, struggling to get on with one another and prone to the occasional outburst of violence. And this is a vision of the village's virtual playground: Little Big Planet.

VOICE FROM GAME:

'On Little Big planet, you're a little sack person. '

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY:

Dubbed the Facebook of video games, it promises to provide a place where people from across the globe can meet and play together in new ways.

Launched in 2008, it looks like a cuddly version of Manic Miner. A platform game in which the player runs and jumps across a childlike landscape of building blocks and poster paint.

But beneath the surface layer of smothering cuteness lies a technological marvel. A powerful, elegant, game construction set that allows players not just to play the game, but to create new ones, which they can publish across the internet. Thus helping to build a bigger, better, Little Big Planet.

The game's a world away from the mean streets of Grand Theft Auto, but just as groundbreaking, so I've come to Brighton to find out more from its creators.

So what inspired the idea of Little Big Planet? Where did the idea come from?

MARK HEALEY:

A huge inspiration for me was my early experience with home computers when they first came onto the market, kind of in the '80s.I was personally more interested in creating things, and home computers then used to come with little manuals that taught you how to programme and that feeling that you got from actually creating something and showing it to other people was really an empowering kind of thing.

That was kind of the seed of Little Big Planet, I think.

December 2008

Rolando for iPhone – Dawn of the mobile games era

In 2008 Apple opened its App Store for the first generation iPhone – a revolutionary smartphone which offered new opportunities for game developers.

In Rolando, the first game made by London studio HandCircus, players rolled ball-like creatures through obstacles by touching and tilting their phone. It was one of the first games to show how intuitive a smartphone was as a games platform. This opened up the world of games to a new audience. Rolando was many critics' iPhone game of the year, and won Pocket Gamer’s Platinum Award. A sequel was released the following year; together they have been downloaded 2.9 million times.

Watch some of the early demos of how to play Rolando on a touchscreen smartphone.

September 2013

Grand Theft Auto V – British franchise breaks sales records and new games territory

The release of the fifth episode in the Grand Theft Auto series broke new records and marked the franchise's global dominance.

DMA Design, now known as Rockstar, had in 1999 been sold to an American company for $11m. Foreign investment had propelled the game to new heights. Game development was still led by a Scottish team, but there were now 1000 people working on it worldwide. At a cost of £170m, more than most Hollywood blockbusters, it was the most expensive video game made to date. But within three days of release it broke the world record for the fastest video game to reach a billion dollars in sales.

Rory Cellan-Jones reports on the huge ambition and big business of Grand Theft Auto V.

Grand Theft Auto V – British franchise breaks sales records and new games territory

Video transcript: clip from Working Lunch, first broadcast on 17 Sep 2013

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

Grand Theft Auto V is a violent 18-rated game with extraordinary graphics and a cinematic sweep.

Keza MacDonald reviews games for a living and she thinks this sets new standards.

KEZA MACDONALD:

In terms of writing, in terms of scripts, just in terms of how well made it is. It’s probably the most cinematically ambitious video game ever made. It’s the kind of videogame that, certainly when I was younger, I imagined that we might one day be able to make. It isgigantic.

RORY CELLAN-JONES:

It’s been 5 years in the making and it seems the budget for Grand Theft Auto 5, 170 million pounds was bigger than for just about any Hollywood blockbuster. But the last version made more than that in its first week, around 315 million pounds. By contrast the highest grossing movie opening was a Harry Potter film which took just over 300 million pounds.

Now it’s thought the latest Grand Theft Auto could make over 500 million in its first week.

April 2014

Monument Valley – Beautiful British mobile game sets new standards

Despite early successes, Britain fell behind other countries in the development of mobile games. But studios here were soon catching up.

Monument Valley was one of the standout mobile games to showcase British creativity once again. Made by London studio Ustwo, the mobile puzzler was critically acclaimed for its exceptional art and sound design. As of January 2015, the game has topped the paid app download charts in 68 countries, been installed on 10 million smartphones and made a $4.5m profit. Ustwo stands alongside many British studios now turning to mobile games.

News reporter Philip Hampsheir looks at how developers are hoping to find the next big hit such as Monument Valley to earn them huge rewards.

December 2014

Seabird - Government backs a new golden age of gaming

To boost the British games industry, and indicating its importance to the economy, the government offered tax relief on production of British games.

One early benefactor has been Seabeard – HandCircus’ latest role-playing game for smartphone and tablet. Players are charged with rebuilding a legendary pirate’s island, meeting quirky characters and trading with others. Praised for its console-like 3D gameplay, Seabeard has had over four million hours of play in just two months. British studios are applying their skill and flair to the newest technology as the UK industry continues to grow.

Ian Livingstone reflects on how video games have reached their widespread popularity today, and looks forward to a new golden age in Britain to come.

Seabeard – Government backs a new golden age of gaming

IAN LIVINGSTONE:

British video games started with a small group of hobbyists – mainly young male gamers playing behind closed doors.

Today, over half of us in the UK play video games. We spend an average of 8 hours a week gaming. And 42% of all players are now female. Never before has video gaming had such broad appeal and huge market value.

And Brits continue to be at the forefront of developing games, with our creativity, ingenuity and computing prowess.

Mobile gaming means we’ve returned, in some ways, to the era when bedroom coders like Matthew Smith created quirky little games that became great British classics.

Here in one of London’s tech hubs, start-ups are looking to create the next big mobile game.

With the opening of mobile app stores, games developers can come up with an idea, craft the design and self-publish in a matter of months.

At the last official count in 2014, there were almost 2,000 video games companies up and down the country, supporting a 2.5 billion pound British market.

Now the government has recognised the value of the video games industry by introducing tax breaks, with Seabeard being one of the first to benefit.

And computing is now firmly on the British school curriculum, which encourages young people to express their creativity and get involved in the video games industry.

With our flair and innovation, I feel we’re standing on the brink of a new golden age of British video gaming.