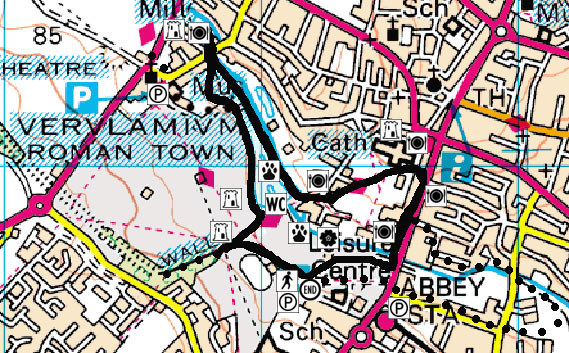

Start Point: Westminster Lodge Leisure Centre, Holywell Hill, St Albans

Countryside Rangers Office: 01727 848168

Ordnance Survey: Landranger 166 - map ref:151065

Distance: approx 3km (1.8 miles)

Time: approx 1 hour 15 minutes

Walk Conditions:

Most of this walk is along man-made concrete paths and pavements although there are opportunities to go off-road and explore on the grass which can become muddy after rain. There are two short hills of a fairly low gradient and a steeper hill which you only have to walk down. If you choose to take the optional trail down to Sopwell, the river bank paths can be narrow and muddy and not always suitable for prams and wheelchairs.

You can either keep to the concrete path or walk on the flood plain grass itself - an area that is widely used by the public and has many leisure uses.

This area is the flood plain of the River Ver, but although it's difficult to imagine, the river used to flow right through where you are walking.

It was much wider then and probably shallower as well, until humans dug it into deeper ditches and moved it for industrial use to work their water mills. Currently it's pushed right over into the far corner of the valley floor. If you stand and face the Abbey, it runs in a channel where the trees start and the grass finishes. You can walk across to see it, if you have time, but there will be other chances further on in the walk.

The River Ver is what's known as a chalk stream which rises north of Redbourn (Kensworth Lynch) and joins the River Colne at Bricket Wood.

The Ver, like other chalk streams, has a porus bed which means that water filters through it and it relies on a high water table for its very existence.

The chalk lying beneath your feet now, can be dated back 80-100 million years when the whole of north west Europe was beneath the sea, and most of it was created by the algae living in it.

The chalk is composed of tiny little plates formed from the algae, which are known as coccoliths. These are very pure calcium carbonate, which the algae extract from the sea water which are then secreted as white calcium carbonate.

The chalk has been here far longer than the Ver, which is not the only river that has run through this area. In fact, it is the legacy left by a far more famous river and, if it wasn't for the ice age, St Albans may well have been England's capital city!

Between 2,000,000 and 450,000 years ago, the River Thames ran through the vale of St Albans, which is the broad open valley between the hill that St Albans sits on and several miles to the south where you now find Radlett and Shenley. i.e. where you are now walking!

To your right you can see the Abbey on the hill. There's quite a steep slope leading up away from the flood plain, to the Abbey and the rest of the city, although it's quite hard to see this through the trees. But behind you and to your left, there's a much gentler slope on the southern side of the valley.

The reason for this is that most of the shaping of the valley occurred under very cold conditions, during the Pleistocene period.

The ground would freeze to a depth of 50 or 100m so the whole of the upper part of the chalk would have frozen and therefore become impermeable.

The rainwater couldn't get into the ground, so instead it ran over the ice and created valleys by erosion.

Northern slopes like the one that the Abbey sits at the top of, got more sunshine than the southern sides of the valley, like the one behind you.

When the sun hit the ice, the permafrost layer melted and sludged down the valley. Because it got more sun, this process occurred much more strongly on the north side of the valley, which became less stable than the southern side.

The meltwater flowed down the slope carrying ground material and undercut the slope making it steeper.

The southern slope would tend to remain stable and was covered by a soil layer that wasn't transported anywhere as rapidly.

When you reach what remains of the London Gate and Roman Wall, you are standing at the eastern end of the Roman City of Verulamium, where the road from London, called Watling Street, entered the city through an enormous triumphal arch.

Here you can see the remaining foundations for a very large gateway and also the largest part of the old Roman Wall that remains. The gate would have consisted of two very large drum towers, with the outside part of the wall rounded, two archways for vehicles and troops and then two smaller ones where people could walk through without being mown down by a chariot!

You can see that the wall is made up of layers of red Roman bricks with about a metre of flint between these brick layers.

Flint was an obvious choice for the Romans to build their wall with because there is a lot of it in this area and it is extremely durable. You can also see it in many other buildings in the city because it's so hard and persistent that it resists any weathering.

The flint was formed around the same time as the chalk. As well as the chalk-forming algae, there were also animals composed of silica living in the sea. After they were buried in the chalk sediment, the silica was redissolved then reprecipitated as flint.

Sadly, most of the wall is now gone. This is not because of weathering but because people came down here to rob the old Roman city for building stone.

So why was Verulamium built here? Well, the river is important but if you look in front of you, you can see that the hill goes up on the northern side of the valley, and from the top you can see for miles. The city may be in a fairly flat valley but it's in a very commanding position and you'd have had a very good vantage point, particularly from the northern side.

As such, the lay of the land has always helped to make it an important area for human settlement.

You can now take the time to walk up along the length of this part of the wall, if you have time.- or turn and walk back down towards the lake.

From here there is also a very good view of the river valley's southern slope, which runs down to the river irregularly.

A lot of this irregularity is archaeological. Here you are looking towards the centre of the Roman city and beneath the grass are all sorts of foundations of buildings, shops and old streets

But some of the irregularity of this slope was created during the very cold stage about 10,000 years ago by the formation of large masses of ice on the ground surface.

The upper layers of chalk were frozen but springs still flowed out from the side of the valley. The water would then freeze on the ground surface forming large masses of ice, 20-40 metres across and several metres thick.

Then sediment would sludge down these slopes and accumulate round the ice, so when the ice melted you'd be left with a little hollow surrounded by sludging sediment, making the ground surface uneven.

Another explanation for the unevenness of this slope is that it is the remains of a Medieval field system. River banks are renowned for having fertile soil so it would have been a very good place for crop gowing.

The Earls of Verulam owned all the land down to the lake, until it was sold to the city council in the 1930s and it was turned into a leisure area by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, with help from the local unemployed!

The lake that you see at the bottom of the slope was built and the river was moved and 'canalised' on the northern side.

But the river used to flow across the valley floor, where you're walking now. Where the lake is used to be a water meadow, a damp marshy area that was grazed on by cattle in the summer.

The lake that is now in the park is of importance for birds and bats and has been designated a Wildlife Site for its local importance.

A variety of wildfowl species can be seen on the lake, ranging from more common species such as the Mallard, Duck, Swan and Coot to more rarer birds like the Great Crested Grebe.

The site is very important for herons which nest on the undisturbed islands in the centre of the lake. If you look carefully, you can see them on the banks around the edges of these islands but they are quite bold now and they can also sometimes be seen in the adjacent river catching fish.

Large numbers of farmyard and Canada geese love this highly man-made environment and have brought problems to the area. You will see that for up to 30 feet from the water's edge, the path and grass is covered in goose droppings.

They congregate here because they know they can get a good supply of food and because of this they don't move onto other sites like they would do naturally. Instead they inbreed and are born with deformities.

You will see that some of the geese have one wing permanently sticking out, looking like they've been in some kind of fight! But this condition is called angel wing and is a genetic deformity resulting from inbreeding.

Apart from this, and the fact that the bread just isn't good for the birds, feeding them causes other problems too - one of this is called eutrophication.

The birds may love a bit of sliced white but the nutrients in it all build up in the water and because there's not a fast flow of the water, poisonous algae grows producing toxins that are dangerous for both people and animals.

The algae also reduces the oxygen levels in the water so there's not enough to support large numbers of fish and insect numbers are also reduced so it has a negative effect higher up the food chain.

The current building known as Kingsbury Mill was built in the 16th century but a mill at this location is mentioned in the Domesday Book.

It was modernised in the 19th century and was a working mill until 1960, powered by the waters of the Ver.

On the grass at the front of the Mill, you will see what at a quick first glance looks like a lump of concrete, but it is in fact a large piece of Hertfordshire Puddingstone. This rock is well-known throughout the world, and can ONLY be found in Hertfordshire, extending into some adjacent counties. But, although there are many theories, nobody really knows why. It's a great geological mystery, so go and take a closer look!

It just looks like a lot of ordinary stones stuck together, loosely resembling a fruit pudding - hence its name! But the geological process that led to this is evidence that St Albans was once a tropical area!

Hertfordshire Puddingstone is composed of pebbles, which are flints derived from the underlying chalk, that have been incorporated into finer sediment.

The unusual thing about Hertfordshire Puddingstone is that the pebbles have been cemented together with silica, which is a very hard material. This silica has been drawn out of the underlying rock by water percolating from the surface of the earth downwards.

When the silica encountered this accumulation of pebbles and sand on its way down, it was re-deposited as a fine material which invaded all the pores between the pebbles and the sand particles and stuck them all together.

But why did this process only happen around here?

It's actually a bit of a mystery but there are various theories. The silica must have originally come from soils near the land surface, where the rainwater percolating through the soil would slowly dissolve silica out and carry it downwards.

But that is a process which is typical of tropical regions, so it must date back at least 50 or 60 million years ago when the climate in this part of the world was something near tropical - very different from anything that we've had since.

Some people say that the silica was much deeper within the earth's crust so when there were other layers of sediment deposited above it, perhaps 100 metres thick, there was a lot of pressure there to assist these chemical changes. But it's a puzzle!

Before you walk round the other side of the lake, stop at the top of it. If it is a Sunday, you can watch the remote controlled boats that people have been bringing to this smaller section of the lake for years.

If you look around you can see a variety of trees in the park including beech, oak, horse chestnut whilst along the river section there are willows and more horse chestnuts.

This area of the park is highly used by the general public, and because a lot of wildlife doesn't like disturbance, you will find more common species in the scrub and hedgerows around here that are more used to people. These include rabbits and all kinds of garden birds like House Martins, blackbirds, chaffinches, robins and tits and of course, pigeons, all of which are fairly bold!

But more unsual birds such as the Greater Spotted Woodpecker have also been seen.

But at dusk, the bats come out!

Bats like to forage along linear habitats such as in the rows of trees along the river to the left, and also in surrounding buildings. This is because being in a line not only protects them from predators, it also aids their orientation.

The bats usually hibernate from late September to late March but at dusk during the summer months, many bat species can be regularly seen feeding over the lake and along the river on insects. These include the common pipistrelle, soprano pipistrelle, daubentons, Brown Long-eared and whiskered bats.

Again you are walking along where the river used to flow, but over the years it has been moved to the left and 'canalised'.

The river on your left is not great habitat now because it is no longer natural. It is all the same level so doesn't get a fast flow of water through it. As a chalk stream, the Ver should normally be associated with brown trout and have water voles on the banks but this artificial bank is not suitable for them. It's far too open.

This kind of slow flowing water also attracts ground dwelling fish like carp which stir up the sediment and make the water look quite murky. Further downstream the water gets faster and is therefore better oxygenated and can support more wildlife.

There are also not many plants here. Planting more vegetation would lead to a greater insect population to feed larger species and also provide good egg laying sites for newts and frogs.

But on the plus side, you will often see lines of majectically swimming swans along this stretch and the horse chestnut trees provide good hauls of conkers for the local children in the Autumn!

The Fighting Cocks pub is officially entered in the Guinness Book of Records as the oldest inhabited pub in Britain, a fact that is hotly disputed by Ye Olde Trip To Jerusalem in Nottingham.

Archaeological digs here have found material dating back to around 1500 but it's also possible that it was also used as a brew house for the Abbey much earlier than that.

This would also make sense because if they were using the river to grind grain in the mills which were owned by the abbot, then they could also have had their own brewery - hence a much earlier alcoholic connection.

On the right there is the Mill Stream and the Abbey Mills, one of a dozen mills that the Ver used to power. These have now been converted for residential use at typical St Albans prices.

It is thought that the river was first diverted for use as water power by the Romans, who moved the river to run a mill when they didn't need it as a defence any more. However, remains were never found when the area was excavated to build flats.

But the Mills are certainly Saxon/medieval in origin, if not earlier, as in the Middle Ages the river was harnessed to power the Abbot's corn mills here. In around 1800, these were replaced by a silk-weaving mill.

To your right you can see kind of water 'steps' coming up from the main river to the Mill Stream. This is a bypass sluice that's been made into a fish pass by the Environment Agency. The theory is that larger fish can migrate up it and recolonise the Abbey Mill stream.

This diversion of the river worked the mill. Because the Ver was a nice swift flowing stream, it was ideal for powering water mills. Just in St Albans alone, there are at least six mills and every time the river has been diverted to power them, it has moved permanently - or as permanent as a river ever is!

If you stand near the gates into the Abbey Mill flats, you can look down to where the water runs. That is the bottom of the valley. The mill stream by the Fighting Cocks is about 20 feet higher and that has been raised by human intervention.

The mill stream travelled under where your feet are now, drove the wheel and went down the mill race. This channel and the river meet again in the Westminster Lodge area.

The Cathedral Church of St Alban looks over the modern city and dominates the skyline.

It marks the place of execution in AD209 of Alban - Britain's first Christian martyr. It was first founded in 792 by Offa of Mercia on the hilltop site where Alban's martyrdom and burial had already been marked by a shrine for over 500 years.

The church you see today is the result of rebuilding in 1077-88 shortly after the Norman Conquest. Its head was made the premier abbot of England in 1154 and it was one of England's greatest abbeys until the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century. It then fell into disrepair until its restoration at the end of the 19th century, becoming a cathedral in 1877.

Norman builders made great use of Roman bricks taken from the ruins of Verulamium - they are best seen in the square Tower.

There is a modern pathway leading up to the Abbey, up the steeper north slope of the river valley as described in stage 2. Under the grass to the right are remains of the monastic buildings such as the hospital, the refectory and the guest chamber, and all the other things that came with a very big Abbey.

St Albans Abbey was famous for its hospitality and although it was wealthy, an awful lot of money was spent on entertaining. A few years ago a rubbish pit was dug up at the top of the deanery and it was full of remains of sturgeon, turbot, pike and venison so we can assume that they ate very well!

The bank before you get to the Abbey would probably have been the limit of the cloisters. Here you can feel you're walking on fairly hard ground.

As you walk down the hill, the variation of the steepness of the slope is very clear, and this is down to the different rates of sedimentation of the underlying rock.

Looking down the Hill you can clearly see the difference in the two slopes on either side of the river valley. There is quite a steep hill going down, but at the bottom, the slope going up again is much more gentle.

Nevertheless, this steep hill provided the main thoroughfare between London and the north and if you were coming from London up the hill it could cause a problem.

Imagine a four or six horse coach in winter coming down St Stephens Hill and braking, before getting into top gear to get up Holywell Hill. It was a terrible strain on the horses, and also caused other problems - especially if you needed to do a hard right into one a coaching in.

In front of you on the other side of the road you will see a hotel. The White Hart is a classic coaching inn. The stables were under the archway and you needed a very skilled coachman to turn right on the hill into the inn.

There was one unfortunate episode, where a lady was travelling on top of one of these stagecoaches because it was cheaper. It made such an enormous turn into the inn, almost like a bus, that she forgot to duck and literally lost her head!

This was the main road to the north though and was probably as congested as it is now! The old A5 and A6 met at the top of the hill and it was an extremely busy junction. People used to sit on the balcony of the inn on the corner to watch the accidents! Big cars would turn there, and collide and watching was a Saturday afternoon pastime in the 1900s, before football took over, that is!

St Albans was, and still is an important junction in the south east network. Just to the south of the modern city sits the junction of the M1 and the M25 and with the A1 running along its eastern side, it is still one of the main routes to the north.

It was the natural flint in the Roman walls that provided the perfect foundations for road construction in this area.

Between the roadmakers and the builders it's amazing that there's anything left of the walls at all, and all this from a Roman town that was bigger than Pompeii. Just think, if St Albans had had a volcano, things could have been so different - but with underlying chalk - that was never going to happen!

Mind you, less than a tenth of Verulamium has been excavated so you never know what might still be found.

At the bottom of the slope you can clearly see the different gradients in the slope. When the chalk was being deposited, it wasn't just a continuous deposition of white calcareous ooze on the sea floor. There were areas where the sediment was accumulating more rapidly and areas where hardly any was accumulating at all.

Where you have areas of slow deposition, you get reactions between the sediment that has already been deposited and the overlying seawater. These reactions have the effect of hardening the sediment and are known as hard grounds.

This hard chalk rock occurs at a level within the chalk between what is called the Middle chalk and the Upper chalk. In St Albans, it occurs some way above the level of the floor of the Ver valley and because it's a hard layer it forms a bench running along the valley sides.

You can see it here in Holywell Hill where half way up the hill there's a gentler slope which marks the top of the bench where the chalk rock occurs.

Below that you've got a steeper slope cut in softer Middle chalk, and above it as you go up from Sumpter Yard to the top of Holywell Hill you've got another steep part, cut from the Upper chalk.

This is the River Ver as it is now, where the mineral rich water is vital to plants and animals of the valley and the wetlands are slow to freeze which make it a temporary haven for migratory birds. And if you see a fantastic splash of blue, it may be a kingfisher!

In front of you, extending out into the flood plain, there is now an area left alone to be a bog because it just wouldn't dry up! It is in fact purely the ground water making a lovely marshy area. It was the River Ver just doing what it wanted to do naturally!

It's now left as an area of unmown grass where reeds and other aquatic plants also appear. Even in summer you can see pools of water on the surface.

Along this part of the river you can really see a difference from the artificial canalised part of the river by the lake.

The water is flowing faster and looks generally clearer and of better quality, providing spawning areas for fish, such as Brown Trout. The vegetated banks attract more small mammals and the running water means it is not only better oxygenated for fish but also provides a rich habitat for invertebrates including stoneflies, beetles, spiders, and dragonflies. As a result the bats like it more down here, especially as it is also quite sheltered.

The undisturbed banks here, and further down in the Sopwell meadows, are more suitable for breeding birds and for water voles to burrow into as they can also feed on bankside vegetation where there are around 230 different types of plant species.

If you spot a water vole, it's helpful for the Wildlife Trust if you let them know, because they are the fastest declining mammal species in Britain, with their population having reduced by 95 per cent since the 1950s. This is mostly due to the introduction of another non-native species into the environment and one which you may also spot - the American mink.

Unlike otters, which don't have a negative impact on water voles, the minks are a bit smaller and can get into the voles' burrows, and as a result has devastated their population.

However, don't get the water vole confused with the brown rat which is roughly the same size!

| Water vole | Brown rat | |

| Blunt nose | More pointed face | |

| Shorter furrier tail | Long hairless tail | |

| Very small ears - can hardly be seen | Ears stick up | |

| Quite cumbersome in the water. Jump in and swim with most of its body above the water so it looks like it's doing a doggy paddle | Slide into water so don't really hear them. They glide in the water and only their heads will stick out of the water. |

There are also some dead trees along here which are an extremely valuable habitat for insects and funghi. Woodpeckers and bats might also roost in them and be able to feed on the insects.

Chalk rivers like the Ver have a characteristic plant community with lots of things to look out for. They are often dominated by mid-channel plants such as Water-crowfoot and Water Starwort. You can look for Water-crowfoot here, and also if you take the extra walk further downstream. It has white flowers earlier in the year and can make the whole stream look like it is covered in petals.

The Ver's low banks also support a range of water-loving plants like forget me not, cotoneaster (garden escape) and of course, the obligatory nettles!

The little brick building, carefully hidden by trees in the middle of the flood plain is the Mud Lane pumping station, which works in tandem with Holywell and Stonecross, up by the Jolly Sailor pub at the top end of the town, pumping water from the chalk.

The chalk is about 600 metres thick in this area of Hertfordshire and perfect for holding water because it acts like a sponge. All you need to do is dig a hole and the water seeps into it. We pump it out and there's our water supply.

As you walk back towards Westminster Lodge, remember that hundreds and thousands of years ago you would be sloshing through water! But where you are walking is also at a higher level than it was during those times.

This area was used as a place to dump the excess soil when the park was re-developed in the 1930s and so is artificially raised. You are also walking on the silt from the dredgings of the lake in the 50s and the 70s. There's also some of the spoil from the construction of the surface of the running track ahead of you.

But even though a constant round of human intervention has raised the ground level, during wet winters (and even summers!) there is some flooding. The grass becomes very marshy and boggy and walkers can get a picture of what the river used to be like.

We hope that this stroll through time has shown how the formation of the landscape and its associated features millions of years ago is a process which is forever evolving. And it also illustrates how we have used our natural resources in ever more sophisticated ways as life gets more complicated.

Over the years the river Ver has proved itself to be a natural resource in many ways. It has always been used to provide a drinking water supply for human beings but other uses have included defence, a source of power and a focus for recreation and leisure.

The underlying chalk has supported and fed this river for millions of years and this rock has also provided us with flint for tools, defence building materials and the construction of the roads that have made St Albans an important centre of communication for centuries.

Who knows what will happen next?

BBC Beds, Herts and Bucks would like to thank the following for all their help in producing this Walk Through Time:

Mike Dodds, Open University

Andy Hardstaff, Countryside Management Service

Dr John Catt, Hertfordshire Geological Society

Andy Webb, Ver Valley Society

Brian Adams, St Albans Museums

Michelle Henley, Herts and Middlesex Wildlife Trust