Rosslyn Chapel has intoxicated visitors from the writers of poetry and fiction to modern Grail hunters. This article offers a history of the building as well as answers to the many questions raised in "The Da Vinci Code".

Rosslyn Chapel

By Michael TRB TurnbullLast updated 2009-08-06

On this page

Page options

History of Rosslyn

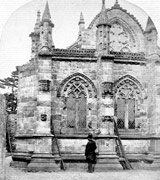

Rosslyn Chapel. The scaffolding is part of a conservation project to allow the stones to dry out naturally. Photo: Thomas Duesing ©

Rosslyn Chapel. The scaffolding is part of a conservation project to allow the stones to dry out naturally. Photo: Thomas Duesing ©Officially known as The Collegiate Church of St Matthew the Apostle, Rosslyn Chapel has intoxicated every visitor, especially the writers of poetry and fiction - from Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth in the nineteenth century to the novelist Dan Brown in the twenty-first.

What makes Rosslyn Chapel unique is that it stands in Roslin Glen, a river channel hidden by towering trees and steep with twisted rock faces. It is an environment that is managed by a number of agencies such as Scottish Natural Heritage and the Scottish Wildlife Trust, a nature reserve protected for its ancient unspoilt habitats.

Rosslyn Chapel was built in the mid-15th century by William Sinclair, first Earl of Caithness. The Sinclairs are descended from Norman knights. Rosslyn was founded as a Roman Catholic collegiate church; today it is a church in the Scottish Episcopalian tradition and still functions as a working church, in spite of the great numbers of tourists who flock to Roslin Glen simply to gaze in wonder at the Chapel, Castle and Glen, searching for spiritual healing in one form or another.

History of Rosslyn

Rosslyn Castle ruins. Photo: Supergolden ©

Rosslyn Castle ruins. Photo: Supergolden ©What most visitors do not appreciate is that there are three Rosslyn Chapels. The first chapel nestled inside Rosslyn Castle within a curious curved stone wall known as the 'rounds', resembling a honeycomb. Two ruined stone buttresses in Roslin's graveyard are all that is left of the second chapel. Construction of the third chapel began in the 1440s on a hill overlooking both its predecessors and lasted forty years.

Sir William founded the Chapel to offer prayers for his ancestors and his descendants and for all mankind. He had had an active life, lived in obedience to his God and to his King, and wanted to ensure that he would reap an eternal reward after death. He established a financial trust that would pay for priests and singing boys to praise the Lord in perpetuity.

Building a collegiate church beside Rosslyn Castle was a way of getting some of the spiritual benefits of a large monastery without the enormous construction this required and the expensive manpower that a big community of monks needed.

The Collegiate Church of St Matthew was intended to be a much larger, cross-shaped building. By the time its founder Sir William Sinclair died, and was buried in the unfinished choir section, his son Sir Oliver Sinclair appears to have either lost interest or run out of money - perhaps the fashion for collegiate churches had simply ended.

Rosslyn Castle, painted by Thomas Bond Walker ©

Rosslyn Castle, painted by Thomas Bond Walker ©For whatever reason, the larger building was never finished: Sir Oliver did no more than add a roof to the choir, which became the entire building. 19th-century excavation work reportedly showed that the foundations laid according to the original plans extend some 91 feet (around 28m) beyond the existing west wall.

At the Reformation (1560) the Chapel was closed for public worship and the Sinclair family forced to break down the altars and discard the carved saints of the old Catholic faith. It was not until 1861 that Rosslyn Chapel opened again for public worship, this time in the Scottish Episcopal tradition. It continues today as an Episcopal church.

Fr Richard Hay

Almost everything we know about Rosslyn Chapel and the Sinclair family goes back to the historical records written down by Fr Richard Augustine Hay (1661-1736/7). Hay, baptised a Protestant, lost his father and his mother married into the still-Roman Catholic Sinclair family. Hay studied to be a priest at the Scots College in Paris and then was ordained as a priest in the Augustinian Order.

Rosslyn Chapel, courtesy of Michael Turnbull

Rosslyn Chapel, courtesy of Michael Turnbull Aside from preaching, celebrating Mass and hearing confessions, baptising, marrying and anointing the dying, taking funerals and all the other things priests might be expected to do, his great interest in life was making sure that precious family charters and their contents were preserved. He did this by copying charters and, as a member of the important Sinclair family, he was given privileged access to the private papers of his and other families.

None of these original charters survived (some were so old and damaged by long use that they would have been copied and re-copied) - although, curiously, a charter recording gifts of land to the canons of Rosslyn Chapel recently came up for sale on an auction site but failed to reach its reserve.

Hence, the manuscripts of Fr Richard Augustine Hay, preserved in the National Library of Scotland, form the main source for the history of the Sinclairs and of Rosslyn Chapel.

Door to Rosslyn Chapel ©

Door to Rosslyn Chapel ©Writers and artists

Many writers, painters, photographers and poets have found beauty and inspiration at Rosslyn. Among these were the writers and poets Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, William Wordsworth, the painter David Roberts and the photographers Hill and Adamson.

Burns and Wordsworth, blown away by the Chapel and the beauty of the surrounding landscape, wrote affectionate verses, while Scott not only penned a haunting poem - The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) - but also, in his Knight Templar novel The Talisman (1871), used the interior of the church at Rosslyn as his bewitching Chapel of the Hermit of Engaddi.

More recently in this long line of creative writers was Dan Brown with The Da Vinci Code (2003, and 2006 film), which uses the Chapel as a key location in its quest for the Holy Grail. The book and film's connection with Rosslyn is covered in detail in a later section.

Stonework

Rosslyn exterior. Photo: Stara Blazkova ©

Rosslyn exterior. Photo: Stara Blazkova ©Tiny as Rosslyn Chapel is, Sir William ordered his architect and stonemasons to create a building decorated with as many biblical and theological stories as possible, but also allowed his stonemasons to let their imagination run riot and carve jokes, green men, monsters and mysteries into the stone.

Of course, the greatest mystery was the gift of life itself and this is what the Chapel celebrates - terrifying evil but also the unquenchable generosity that the mediaeval world saw in the Old Testament and in the drama of the life and death of Jesus.

In the 1860s the Fourth Earl of Rosslyn, Grand Master Mason of Scotland, replaced many of the damaged carvings, changed a number of other stone features and inserted stained glass, painted railings, a central altar and pews.

Monsters

Outside the Chapel there are stone lions violently thrusting out like the monster in Ridley Scott's Alien. They are in fact elaborately concealed parts of the drainage system for the roof. Other carvings outside have fared less well, so badly eroded that it is difficult to make out what they are supposed to be. This adds to the fascination as the onlooker's imagination fills in the gaps.

This indecipherability produced by erosion and damage is what led the Fourth Earl to 'improve' the Chapel in the 1860s, replacing stone bosses (carved features covering the junction of upright pieces of stone with horizontal supporting stones) with invented quasi-Masonic carvings. In a sense the Fourth Earl dressed Rosslyn Chapel up in the then-popular Pre-Raphaelite style of imagined Victorian mediaevalism.

Jokes

There are smiling and grinning faces all over the Chapel. Some of the smiles and grins are close to insanity, so there is an edge that makes you never quite sure when you are being made a fool of.

A Green Man. Photo: Landhere ©

A Green Man. Photo: Landhere ©The Earls of Rosslyn annually entertained travelling gypsy troops who were housed in Rosslyn Castle and presented popular Robin Hood plays. The pre-Reformation Roman Catholic Church did not take itself too seriously: each December the Abbot of Unreason presided at Holyrood Abbey and on New Year's Day the 'King of the Bean' ruled.

But in 1579 (almost twenty years after the Scottish Reformation) the Robin Hood plays were banned and all minstrels, pipers, fiddlers and singers of profane songs expelled from Edinburgh and its surroundings.

In Rosslyn Chapel there is fun everywhere - in the faces of the many minstrels strumming their mediaeval guitars or blowing their own trumpets lustily.

Apprentice Pillar

The master stonemason, so one legend goes, had received the design for a pillar. The carvings were so intricate that he was reluctant to begin work on it until he had travelled to Rome to see the original. While he was away, the mason's apprentice had a dream that he had finished the pillar. He set to work and by the time the master mason returned, the pillar was complete, a masterpiece of stonework. The mason was not pleased and killed the apprentice on the spot with a hammer-blow to the head.

Master and Apprentice Pillars, courtesy of Michael Turnbull

Master and Apprentice Pillars, courtesy of Michael Turnbull The Apprentice Pillar (also called the 'Prentice Pillar or Prince's Pillar in earlier sources) is entwined with carved vines. Its architrave bears the Latin inscription forte est vinum, fortior est rex, fortiores sunt mulieres: super omnia vincit veritas, meaning "wine is strong, the king is stronger, women are stronger still: (but) truth triumphs over all".

Also to be found in the chapel are the carved heads of the master mason, the apprentice (complete with wounded head) and the apprentice's grieving mother.

Fascinating as this legend is, it is not unique to Rosslyn. The story of the Master and the Apprentice pillar is a cautionary tale told by the older craftsmen to the young apprentices to prevent them getting ideas above their station! 'Apprentice Pillars' and similar stories occur in many mediaeval churches, not only in Britain: there are gashed apprentice heads all over Europe.

The pillar in Rosslyn was made by an expert stonemason. No apprentice would have the skill to carve such a masterpiece.

Corn, aloe and mysterious foliage

The Apprentice Pillar. Photo: Beau Wade ©

The Apprentice Pillar. Photo: Beau Wade ©Rosslyn Chapel is full of leaves and plants carved in stone. Could any of them represent real plants, and is a trans-Atlantic mystery hiding among the carvings?

Dr Adrian Dyer, a professional botanist and husband of the Revd Janet Dyer, former Priest in Charge at Rosslyn Chapel, meticulously examined the botanical carvings in the Chapel. He looked at carvings of leaves that are claimed to be curly kale, oak leaves, cactus leaves, sunflowers and three-leaved botanical forms (trefoils).

Broadly speaking, Dr Dyer found the botanical forms in the Chapel to be stylised or conventionalised, not meant to be identifiable plants, with one exception. Hart's-tongue fern, an ancient fronded plant, was growing in Roslin Glen in the fourteenth century and is still found today under Rosslyn Castle. It can be seen, approximately life-size, carved on the Apprentice Pillar.

With respect to the fruits and flowers and their possible symbolism, the three-leaved flowers may be seen as references to the Trinity. However, the flowers in the roof which early guides described as 'daisies' are not true representations of that flower. There are some carvings which are reminiscent of the Madonna lily and may therefore have religious significance.

The Rosslyn 'corn' carvings. Photo: Kjetil Bjornsrud ©

The Rosslyn 'corn' carvings. Photo: Kjetil Bjornsrud ©One window in the Chapel is surrounded by carved plants that are claimed to be maize and aloe, two species that are native to North America and had not yet reached Europe by the 15th century, when Rosslyn was built. They have been used to support theories that William Sinclair's grandfather, the explorer Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, had secretly travelled to the Americas before Columbus.

This idea does not bear scrutiny. Dr Dyer found that there was no attempt to represent a species accurately: the 'maize' and 'aloe' carvings are almost certainly derived from stylized wooden patterns, whose resemblance to recognisable botanical forms is fortuitous.

Much the same conclusion was reached by archaeo-botanist Dr Brian Moffat, who also noted that the carvings of botanical forms are not naturalistic nor accurate. He found a highly stylised Arum Lily the most likely candidate for what has been identified as American maize.

As for the 'aloes', Dr Moffat points out that the consumer would never have seen the plant, only the sap which was used medicinally. There is no citation of either 'maize' or 'aloe' in the Oxford English Dictionary before the mid-sixteenth century; aloe was not imported to Spain until 1561. Moffat adds that "In common with the majority of Rosslyn's foliage, little life is on display and precious little nature."

Green Men

Green Man. Photo: Johanne McInnis ©

Green Man. Photo: Johanne McInnis ©A Green Man is a depiction of a man's head made of, or surrounded by, leaves. They are common decorations in both churches and secular buildings, mediaeval and onwards.

Green Men originated in pre-Christian times and are often associated with ancient Pagan nature deities. They symbolise spring, new life and rebirth: fitting themes for Christian worship.

Rosslyn has many Green Men around its walls, beginning at the east, with young faces symbolising spring, through south and west, with ageing faces as autumn approaches, and ending at the north where the faces are skeletons.

The Green Men make the visitor laugh at the sheer exuberance of the foliage coming out of a grinning mouth. At the same time the image is ironic, as it seems to undermine the pomposity of organised religion by introducing elements of chaos. Green Men show the intimate connection between the human race and the environment.

You could argue that Jesus Christ was a Green Man in that he was a carpenter by training and died on a wooden cross!

Light-box

A carving. Photo: Landhere ©

A carving. Photo: Landhere ©John Ritchie, journalist and historical researcher, and Alan Butler, historical writer, have described their discovery of a small red piece of stained glass at the apex of the East Window. Twice a year, at the summer and winter equinox, the sun shines through the Chapel and bathes it with red light. (See related links for a clip.)

However, Mark Bambrough, the mediaeval stained glass expert, shows authoritatively in 'Rosslyn: A Glazing History' that all the stained glass in Rosslyn Chapel dates from the 1860s, when the Fourth Earl of Rosslyn had it installed, dates from the Victorian period.

The mediaeval stone tracery was also removed in the 1860s to make way for the stained glass that can be seen today. Bambrough's opinion is that there never was any stained glass in the Chapel in mediaeval times - only uncoloured glass, if any.

William Sinclair

A carving of the Chapel's founder himself is found underneath the apprentice's head.

Da Vinci and Templars

Could Rosslyn be the hiding place of the Holy Grail? ©

Could Rosslyn be the hiding place of the Holy Grail? ©As a Rosslyn historian, I don't have a problem with Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code: it's a work of fiction. It's a rattling good read, but it isn't history and it isn't factual.

Was da Vinci connected to Rosslyn Chapel?

Leonardo da Vinci, with whose name Dan Brown entitled his thriller, had very little to do with the Chapel. Leonardo was born in 1452 at the small town of Vinci, twenty miles west of Florence, twelve years after the foundations of Rosslyn Chapel were first put into position. In 1480, when construction on the Chapel was permanently halted, Leonardo would have been 28 years old.

Was Rosslyn Chapel built by Templars?

Rosslyn has nothing to do with the Templar order, despite the modern carving that claims a gravestone in the Chapel is that of a Knight Templar.

The early members of the Sinclair family were knights, but unfortunately Dan Brown does not distinguish between the several William Sinclairs. One Sir William Sinclair was killed in battle against the Saracens at Teba in Spain on 25 August 1330. He had been en route to the Holy Land with a number of other Scottish knights, charged with taking the heart of the late King Robert the Bruce and burying it in Jerusalem.

Sketch of Rosslyn Chapel, courtesy of Michael Turnbull

Sketch of Rosslyn Chapel, courtesy of Michael Turnbull However, this William, and the other Sinclairs, were not Templars. Knights Templar belonged to a religious Order and so swore vows of poverty, chastity (ie they were not allowed to marry) and obedience to the rule of the Order. One or two of the Sinclairs were Roman Catholic canons who served at Rosslyn Chapel and other local chapels that belonged to the family, but the vast majority were rich, married and only owed obedience to the King and the Pope above him.

The Sinclairs, in other words, were not Knights Templar but Crusaders who went on a Crusade to the Holy Land.

The Chapel was built by mediaeval architects who had worked their way through the craft of the stone mason from apprentice to master architect. Some of their designs have survived - such as the sketch-books and pattern-books of the French mason-architect, Villard de Honnecourt (c 1175-1240).

Mediaeval architects were not Knights Templar but builders. They travelled around Europe teaching, learning and constructing. They were not professional soldiers like the Templars.

Does the stonework contain Jewish, Muslim and Pagan images?

Carvings on the upper level. Photo: The_Majestic_Fool ©

Carvings on the upper level. Photo: The_Majestic_Fool ©The symbols in Rosslyn Chapel can all be related to the Bible, in particular to the Old Testament and the Psalms. The Psalms were part of the Divine Office (known as the 'Opus Dei') sung by the canons and choirboys at Rosslyn at regular intervals throughout the day and night. Since Christianity was founded by Jews it is natural that it should continue to use the Hebrew Bible (even if translated into Greek or Latin). The Roman Catholic Mass and other services to this day contain many formulae, expressions and gestures that are characteristically Jewish.

Christianity shares with Judaism and Islam a belief in one God. The notion of salvation and mystery goes back to the book of Genesis and continues with events such as the escape of the Jews from slavery in Egypt and the wanderings of the People of God in the desert.

All this and more is dramatised in the carvings at Rosslyn Chapel. The Roman Catholic Church was never afraid of using Pagan symbols such as the Sun or the Moon. In fact the early missionaries sent to England with St Augustine in the sixth century were specifically told to destroy the Pagan shrines and build the Christian churches over the site!

Does the stonework honour nature and the female divine?

It certainly celebrates nature.

Christians believe that God created the universe, the sun and the moon, the earth, human beings and animals. This is the great Creation story that can be found in the Book of Genesis which emphasises the connectivity between human beings and their environment.

The ceiling in Rosslyn Chapel, covered with stars and flowers. Photo: Landhere ©

The ceiling in Rosslyn Chapel, covered with stars and flowers. Photo: Landhere ©Standing in Roslin Glen of a summer's day it is easy to revel in the wonder of Creation. This is celebrated in the riotous profusion of carvings in Rosslyn Chapel.

Christanity does not contain goddesses who are worshipped but the Virgin Mary is honoured as the Mother of Christ and the eastern part of Rosslyn Chapel (the Retro-Chapel) is sometimes called the 'Lady Chapel'.

Are there hidden messages in the stonework?

There could be. Plenty of creatures, symbols and funny figures can be discovered in Rosslyn's carvings. But using stonework to express unorthodox religious beliefs, even disguised ones, would have been a risky business.

Rosslyn Chapel was built in the mediaeval period when feudalism required that every knight or baron provide fighting men when asked by the king. Kings were in turn subject to the moral authority of the Pope and to the requirements of canon law as a ruler under God. In other words, orthodoxy was synonymous with temporal and spiritual authority.

Power, titles and lands were bestowed by mediaeval kings as rewards for service - generally military service. Deviation, treachery or alternative religious beliefs were punished by death!

Is Rosslyn named after the Paris Meridian or 'Rose Line'?

No. Rosslyn is generally taken to be derived from the Gaelic for "rock" and "foaming water" - which describes the location of Rosslyn Chapel beside the North Esk River. The river does not have such spectacular rushing water nowadays, as the rocks that caused it were blasted out by the tapestry, linen-bleaching and gunpowder factories in Roslin Glen not far from the Chapel and just below the Castle.

Roslin village, Midlothian. Photo: Richard Webb ©

Roslin village, Midlothian. Photo: Richard Webb ©Rosslyn has no etymological connection with "Rose Line", or "Ligne Rose" as it would be in French.

Is there an underground chamber hidden beneath the Chapel?

The Chapel is built on compacted sand which forms a solid and secure foundation. It is thought that the lower Chapel (also known as the Sacristy or Crypt) was the original Rosslyn Castle, which the Sinclairs abandoned on the advice of an English prisoner-of-war after the triple Battle of Roslin (1330), moving to the present site on a narrow promontory of rock high above the river.

Sir Walter Scott, who came to live nearby at Lasswade Cottage at the time of his marriage, often walked over to Rosslyn (and once nearly slipped down to his death in the river!). His 'Lay of the Last Minstrel' describes the Barons of Rosslyn lying in full armour in the chambers under the Chapel. These chambers would have been part of the foundation reinforcement.

In recent years drilling has taken place with a camera, but as soon as the drill and camera penetrated into these lower chambers sand flowed in. Such invasive explorations are no longer permitted as they would compromise the stability of the mediaeval foundation.

There is no modern office concealed under a trap-door in the Lower Chapel.

Is Rosslyn a replica of Solomon's Temple?

No more so than a usual church. Christian churches are based on the traditions of Judaism, with a sanctuary (Holy of Holies) that derives from the tents that covered the Ark of the Covenant in the desert. Greek and Roman styles of architecture have also been influential in the development of Christian churches. In this sense every Christian church expresses the cumulative history of the Chosen People.

There are some 40 Collegiate churches in Scotland built at approximately the same time as Rosslyn Chapel. Their purpose was to obtain some of the spiritual benefits of a large monastery but much more economically. Hence, the design of Rosslyn Chapel, although architectural historians generally agree that it is based on that of the earlier Glasgow Cathedral, is on a much smaller scale.

Door hinge. Photo: The_Majestic_Fool ©

Door hinge. Photo: The_Majestic_Fool ©Many of the Collegiate Churches built by the nobility ceased construction at precisely the same point as Rosslyn Chapel. The Choir at the east end was finished but the central tower was not completed, nor was the rest of the building whose foundations still stretch 90 feet to the west two metres underground. Construction stopped either because of a change in fashion or because the building was proving to be too expensive.

Dan Brown claims that the west wall is a replica of the Western Wall of the Temple in Jerusalem. In reality the wall, with its northern and southern transepts and its Victorian baptistery, was intended as an interior wall to support a tower and not as a 'Wailing Wall'. It has nothing to do with Solomon's Temple.

Brown also mentions that the subterranean vault is a replica of the Holy of Holies. Since no one can tell what the subterranean vaults are like (see above) this is hard to prove! What is known is that the vaults were used to bury members of the family. In the Temple at Jerusalem, the Holy of Holies was not underground but in an elevated central position.

Are Rosslyn's Apprentice and Master Pillars really Masonic symbols, found in Masonic temples today?

If they are, Rosslyn had them first. Since modern Freemasonry did not exist before the Reformation (1560), whatever is to be found in modern Masonic buildings may be identical but was built a millennium and a half later.

In fact, any Masonic-looking emblems in the Chapel were inserted in the 1860s when the Fourth Earl of Rosslyn, the Grand Master Mason of Scotland, was replacing damaged carvings in the Lady Chapel. Most were so eroded that there was no way of knowing what to replace them with, so the architect, the stonemason and the Fourth Earl designed and executed some mediaeval-looking stone bosses, which seemed to have Masonic meanings.

For the legend of the Master and the Apprentice, see the previous section.

Are there grooves on the floor in the shape of the Star of David?

There are no such grooves on the floor and no Star of David, although visitors come looking for them and are surprised to find they do not exist!

One of Rosslyn's carved columns. Photo: Landhere ©

One of Rosslyn's carved columns. Photo: Landhere ©Is there an archway covered in a secret code?

Rosslyn features a number of small rectangular decorative stone features protruding from a number of arches - and these have been identified recently as a hidden piece of mediaeval music.

This seems an unlikely discovery. It is hard to see why anyone would want to hide such a very short section of music when there was a wealth of Gregorian chant and complex polyphonic compositions available to the canons and singing-boys at Rosslyn Chapel.

Dan Brown mentions an archway covered in jutting symbols and says that "cryptographers [have] been trying for centuries to decipher its meaning" with no success, despite a reward being offered.

However, the father and son who believe they have discovered this piece of music took some twenty years (not centuries) to find it and are musicians, not cryptographers. The Rosslyn Chapel Trust confirms that it has not offered any reward to would-be code-crackers.

Where is the stone roundel from the film?

In the film of The Da Vinci Code, the two main characters enter Rosslyn Chapel and go down the steps into the Lower Chapel. As they do so, you see a small stone roundel above their heads displaying a cabbalistic symbol and surrounded by green algae.

If you go down those same steps today you will see that, instead of a roundel, there is a painted grey disk of the same size with a number on it. This number was probably used as part of the tourist guiding system a few decades ago. The green algae are still there surrounding the painted and numbered disk.

The Holy Grail remains elusive. Photo: Dani Simmonds ©

The Holy Grail remains elusive. Photo: Dani Simmonds ©The 'stone' roundel in the film was in fact made of fibreglass and was removed after filming. The 'algae' were sprayed-on paint!

Could descendants of Jesus and Mary Magdalene be living secretly at Rosslyn?

It's pretty clear that Dan Brown invented this detail for his story. He never claimed it was really true.

The rule of the Merovingian kings ended in 751 AD. The St Clairs came over from France as part of the Norman Conquest after 1066 AD. If Jesus and Mary Magdalene had had children, by 1066 AD their descendants would have multiplied exponentially. It is almost the same as saying that everyone in the world is descended from Adam and Eve or a small number of hominids in Africa.

There is no proof that Jesus had any children other than in the sense of the theological concept that we are all 'children of God'.

References and bibliography

Old photograph of Rosslyn, courtesy of Michael Turnbull

Old photograph of Rosslyn, courtesy of Michael Turnbull About the Chapel

Michael T R B Turnbull, Rosslyn Chapel Revealed (Sutton Publishing Ltd., Nov 2007) ISBN-10: 0750944676; ISBN-13: 978-0750944670

Botanical carvings

Dr Adrian Dyer, A Botanist looks at the Mediaeval Plant Carvings at Rosslyn Chapel, three articles, 2001-02

Dr Brian Moffat, Magic Afoot: Rosslyn Aloes in Veritas?

Mediaeval stonemasonry

François Bucher, Architector: the Lodge Books and Sketchbooks of Mediaeval Architects, vol 1 (New York: Abaris Books, 1979), 13; 170-171

Apprentice Pillar

Robert L. D. Cooper, The Rosslyn Hoax? (Hersham: Lewis Publishing, 2006), 244

Stained glass and 'light box'

Alan Butler and John Ritchie, Rosslyn Revealed - A Library in Stone (Winchester: O Books, 2006), 139-166

Mark Bambrough, Rosslyn: A Glazing History, (Journal of Stained Glass, vol. xxx, 2006), 12-28

Around the BBC

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.