This page provides interviews and a transcript of BBC interviews with Richard Dawkins, a vocal pro-humanist.

Richard Dawkins

Last updated 2009-10-22

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins Richard Dawkins is a British evolutionary biologist who has been outspoken in his support of Darwinism, atheism and secular humanism and opposition to religion.

He has written several popular science books, including the iconic The Selfish Gene (1976), and holds the Charles Simonyi Chair for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University.

Intelligent life on a planet comes of age when it first works out the reason for its own existence. If superior creatures from space ever visit earth, the first question they will ask, in order to assess the level of our civilization, is: 'Have they discovered evolution yet?'

Richard Dawkins, first lines of The Selfish Gene (1976)

'Belief' interview

This is the transcript of the "Belief" interview broadcast in April 2004.

Richard Dawkins holds the Charles Simonyi Chair of Public Understanding of Science in Oxford, and as such he takes a high profile role in the exposition and elucidation of scientific ideas in our culture. He's eminently well placed to do so, being himself one of science's most innovative thinkers.

His first book, The Selfish Gene, made a huge impact back in 1976, with its message of the central role of genes in evolution. There followed a stream of more books, all with highly poetic titles - The Blind Watchmaker, River Out of Eden, Climbing Mount Improbable, Unweaving The Rainbow, and most recently A Devil's Chaplain, each offering further development and commentary upon Darwin's concept of Natural Selection. There is one book whose title is not poetic - The Extended Phenotype - which Dawkins himself believes marks his biggest claim to scientific innovation.

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins Not surprisingly, the many honours he's received include both a fellowship of the Royal Society, and a fellowship of the Royal Society of Literature. Not many people have both.

Richard Dawkins, you came from a family...that lived in Malawi, or what is now Malawi. Your father was in colonial administration, and when you came back to England, he became a farmer. This suggests a secure, middle class conventional background.

Yeah, that pretty much sums it up I think, yes.

And it felt comfortable?

Very comfortable. I was sent off to boarding school, which some people don't find comfortable. I was happy with it, and I had an idyllic time in the school holidays.

And was it there that you decided you wanted to be a scientist?

My decision to be a scientist was a bit of a drift really, more or less by default.

Well you were following in you father's footsteps...

I was following, and that partly helped me to help that drift, I suppose. And I did prefer Biology to any other subject, but it was wasn't really until my second year as an undergraduate at Oxford that I feel I really became deeply enthusiastic about science and about Biology.

What about your faith? You were part of an orthodox Anglican home. Did it impinge very much on your life?

Not much. I mean my parents were orthodox Anglican in the sense that they were both baptised, as was I, but they were not deeply religious, and they are not deeply religious. We used to go to Church every Christmas, but I mean apart from that there wasn't a lot of it about.

You weren't confirmed?

I was confirmed. That was school influence. I was confirmed at my prep school at the age of 13.

Because you've written since about how much you disapprove of children being assigned the religion of their parents.

I do disapprove very strongly of labelling children, especially young children, as something like 'Catholic children' or 'Protestant children' or 'Islamic children'. That does seem to me to be very wicked because what you're in effect doing is making the assumption that the beliefs, the cosmology, the beliefs about the world, about life, are automatically going to be inherited in a way that you don't assume for anything else. And you certainly don't assume that a child will inherit his father's sports team, or love of ornithology, or politics or economics. Religion is the one... of course in practice, children very often do. You very often find that a child will in effect be influenced by a parent to take up bird watching or stamp collecting - that of course is absolutely fine. But society simply assumes, without even asking, that there is such a thing as a Catholic 4 year old, or a Muslim 4 year old. And that I do think is wicked.

But confirmed at 13, read Darwin at 16... this was a big leap was it?

Yes. I didn't actually read Darwin himself. I mean I didn't read Darwin himself until rather later. But I read Darwinism, and understood Darwinism at 16. And that was a big leap for me, because by the time I reached the age of 16, I had lost all religious faith, with the exception of possibly a sort of lingering feeling about the argument from design. So I'd already sort of worked out that there are lots of different religions, and they contradict each other, so they can't all be right - and that kind of thing. But I was left with a sort of feeling 'Oh well there must be SOME sort of designer, some sort of spirit which, which designed the universe and designed life.' And it was when I understood Darwin that I saw how totally wrong that point of view was, that rather suddenly scales fell from my eyes and I then became rather strongly anti-religious at that point.

And there wasn't a sense of loss here? I mean you obviously hadn't had a personal relationship with God, to whom you spoke in your prayers, because to lose that would've been considerable.

Well that's probably right. At the age of about 13 when I was being confirmed, I did have a fairly active fantasy life about a relationship with God, and I used to pray and I used to have fantasies about creeping down to the chapel in the middle of the night, and having a sort of blinding vision and things. I don't know really how seriously I took that.

How seriously do you take it now?

It was a fantasy which happened in my head and it's not surprising that it should have happened in my head, because I was at that time being filled with all that sort of stuff in confirmation classes.

A nourishing fantasy?

I don't think so, no. I don't think it was at all a nourishing fantasy. I don't think it did me much harm, but I don't think it did me any good either.

Now you went to Oxford in the early '60s. By the late '60s you were in California - and we're talking of the decade of student tumult - the questioning of everything. How did this wash over you?

Well I got pretty much involved in it. It was at the height of Vietnam war resistance and most of the students and indeed most of the faculty at the University of California at Berkley were against the war in Vietnam and there was a lot of unrest, there was a lot of demonstration and I got pretty heavily involved in all of that.

Now influences on your life then, as a young student, and ideas emerging - Nico Tinbergen? And someone called Bill Hamilton...

Nico Tinbergen was my doctoral supervisor, and he was a benign, avuncular sort of influence; everybody loved him. Bill Hamilton was a very considerable theoretical biologist, who influenced me hugely, and the influence can be seen throughout The Selfish Gene.

The books started arriving - '76 was The Selfish Gene, Blind Watchmaker '86, River Out of Eden and Unweaving the Rainbow, A Devil's Chaplain. These are wonderful titles - and these are not scientific titles. They suggest that you are a figure with a literary interest, but also a literary sensibility running parallel or perhaps identical with your wish to be clear in the exposition of scientific ideas.

I love words. I think some of the phrases that I've produced as titles for books, I won't say that they hit me as a sort of 'That's it'. I think they grew on me later. I don't actually think The Selfish Gene is a very good title. I think that's one of my worst titles.

But what is interesting about The Selfish Gene is 'selfish' is a judgmental word. Selfish is what you are brought up not to be. So we're saying that we disapprove of the gene. The gene is behaving in a way that actually we don't now think is a good thing. It carries that resonance.

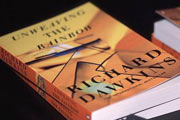

Unweaving the Rainbow

Unweaving the Rainbow It certainly does. It carries that resonance. I'm not sure it carries a very poetic resonance which I think The Blind Watchmaker does. And River Out of Eden, which of course is just lifted straight from Genesis, so that's not surprising that it's poetic. And Unweaving the Rainbow is lifted from Keats.

So the writer is evolving along with the scientist. But The Extended Phenotype is not a poetic title.

No.

And in a way perhaps because you've said it represents what you see as your greatest original contribution, you did want it to have a scientific sounding title.

Well when you introduced this line of discussion you raised the poetic side of the title, because at the same time you said maybe that went with my desire to be clear. But you'd be surprised how many people do not actually want to be understood at all but, I regret to say, want to create some sort of an impression. The Extended Phenotype, as you rightly say, makes no attempt to be poetic, but it does encapsulate very precisely the central message of that book in a way that would be clear to the people that it was mostly aimed at, which was my professional colleagues.

And the books for lay people of course have brought you a huge audience, and people interested in what it is you yourself believe. Let's go through the different concepts then that are often applied to religion, but are words often loosely used. Purpose - the purpose of life - are you satisfied that you understand the purpose of life?

Well 'purpose' is a difficult word, and it's much misunderstood. As humans with consciousness, we have purposes which we actually visualise in our minds and we see in our mind's eye something that we wish to achieve. We're looking into the future, and attempting to achieve something. Purpose is used by biologists in a very different way, but the resemblance comes because the products of Darwinian natural selection look so stunningly as though they have been designed for a purpose. And so something like a wing or a foot or an eye really does carry the most incredibly powerful illusion of purpose. Since Darwin we've understood where that illusion comes from, but it's such a strong illusion that it's almost impossible to resist using the language of purpose.

But where then does the concept of human purpose come from? There must be something within the human psyche that can conceive of a forward-looking...

Well there clearly is, and it's clearly a very strong part of our psyche. And I of course as a Darwinian would see it as yet another thing that has evolved. So just as we've evolved sexual desire, just as we've evolved hunger, we have also evolved a sense of purpose. And the sense of purpose in our wild ancestors would've been hugely useful because you can imagine a purpose of setting out on a hunt, a purpose of looking for a water hole. Those are all very, very useful things, and the human brain was, I don't doubt, selected by Darwinian selection to develop this sense of purpose.

Was the human brain selected to develop religion?

I don't know, but my guess is no. The way I would answer that question is to say that the human brain was selected to develop something which manifests itself as religion under some circumstances. If I take an analogy of... well, one that I'm particularly fond of is the tendency of moths to fly into candle flames, and it's tempting to label that suicidal behaviour in moths, and ask what on earth is the Darwinian advantage of suicidal behaviour in moths. If you put it like that, clearly there isn't any.

But if you say instead 'What is the Darwinian survival value of having the kind of brain which under some circumstances leads moths to fly into candle flames?', then you're getting somewhere, because then you can say 'Well in the world where moths evolved, there weren't any candle flames. The only lights you would see if you were a night-flying moth would be things like the moon and the stars, and they are at optical infinity, which means that their rays are coming parallel. And if you have a rule of thumb in your brain that says 'Steer a steady angle of say 30 degrees to the rays of the moon,' that's a very useful thing to do, because that keeps you going in a dead straight line. That rule of thumb is then misapplied to candles, which are not at optical infinity, where the rays are radiating outwards. And if you follow the same rule of thumb, of keeping an angle of 30 degrees to the candle's rays, then you'll simply spiral into the candle and burn yourself.

So we have rephrased the question. We've said it was the wrong question to say 'Why do moths fly into candle flames?'. The right question is 'Why do they have the kind of brain which in the wild state made them do something which, in the human-dominated state where there are candles, makes them fly into candle flames?'. Now in the case of religion, I think there was something built into the human brain by natural selection which was once useful and which now manifests itself under civilised conditions as religion, but which used not to be religion when it first arose, and when it was useful.

Well given that religion arises in most cultures, do you believe that there are benefits of solidarity, tribal unity, mutual generosity, within religions, that are useful to those communities?

Yes there very possibly are. I should qualify that by saying that as a Darwinian, usefulness to communities is not what it's about. Darwinism is all about usefulness to individuals, or rather their genes, to be more precise. So usefulness to communities is an added benefit, and I'm sure you can list benefits to communities that accrue from religion. I expect you can probably list disbenefits as well. But benefits or not, I don't think that's why it evolved. I think that's a kind of incidental bonus.

One of the things that recurs when you are spoken of, Richard, is the way that you're regarded by the religious in our society, who see you as a bogeyman - a fundamentalist, a scientific Puritan. You have this reputation quite widely - do you feel responsible for it?

I don't particularly mind being a bogeyman - I do mind being a fundamentalist. I think a fundamentalist is somebody who believes something unshakeably, and isn't going to change their mind. Somebody who believes something because it's written in their holy book. And even if all the evidence in the world points in the other direction, because it's in the holy book they're not going to change.

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins I absolutely repudiate any suggestion that I am that. I would, like any other scientist, willingly change my mind if the evidence led me to do so. So I care about what's true, I care about evidence, I care about evidence as the reason for knowing what is true. It is true that I come across rather passionate sometimes - and that's because I am passionate about the truth. Passion is very different from fundamentalism.

You're rather good at invective...

Yes. I mean if that's true, I don't mind it. I do get very impatient with humbug, with cant, with fakery, with charlatans. And so sometimes I am perhaps less polite than might be desirable. But it comes not from fundamentalism but from a passionate belief in the power of evidence.

Let's talk about the three letter word - God. What is interesting is how the use of the word varies now, and that while many people have what in shorthand I might call a 'Sunday School' version of what they believe in God, many people including scientists are using the word 'God' in a much more abstract way. What do you feel about those developments?

Einstein, for example, frequently used the word 'God' in very clearly what was not a 'Sunday School' way. It was somewhere between deism, the belief that some sort of intelligence started the universe going and then stepped back and did nothing else, which actually I don't think Einstein believed in, and a sort of pantheism, where he was using the word 'God' as just a name for the laws of nature, the laws of physics, for which he had a deep reverence, as do I.

Stephen Hawking talks about 'the mind of God'.

Stephen Hawking ends up his famous book by saying 'Then we would know the mind of God' and that's precisely like Einstein. It's a metaphor, a personification, it's a poetic way of expressing 'Then we should know everything, then we should understand everything.' Stephen Hawking was looking forward to a day when physicists finally have unified all their theories and understand everything, and 'Then we should know the mind of God' was a way of expressing that. Stephen Hawking and Einstein: neither of them believes or believed in a personal God.

So which is the God you don't believe in?

I certainly don't believe in a God who answers prayers, forgives sins, listens to misfortunes, cares about your sins, cares about your sex life, makes you survive death, performs miracles - that is most certainly a God I don't believe in. Einstein's God, which simply means the laws of nature which are so deeply mysterious that they inspire a feeling of reverence - I believe in that, but I wouldn't call it God.

What about Buddhism, mysticism, contemplation, meditation?

I know little about Buddhism; meditation as a kind of mental discipline to manipulate your mind in beneficial directions, I could easily imagine. In reciting a mantra in a repetitive way - it's entirely plausible to me that might have some sort of trance-inducing effects which could even be beneficial.

But you don't do it?

I have done it, and it didn't do anything for me, but I gave it a go. But it certainly has nothing whatever to do in my mind with a belief in anything supernatural.

Let's take another religious word - 'evil'. Do you have a concept of evil?

I mistrust the uses of words like 'evil' which suggest a kind of personification of them. I'm happy to use a word like 'evil' of a particular individual. I'm happy to say that Adolf Hitler was evil, Adolf Hitler did evil things, but too many people once again, leap to the conclusion 'Oh there must be some kind of spirit of evil which entered into Hitler,' or 'There's a spirit of evil abroad'. That I think is unhelpful, putting it mildly.

What is the vocabulary that you use to express what you believe?

Well I suppose it's a scientific vocabulary. It's the vocabulary of the real world, but in the rather subtle way that scientists use the idea of the real world.

But where do you draw your values from, if you live in what you might call the mechanistic world of ideas and developing and potential ideas?

Well, if by 'values' you mean 'morals', that would be one question. Another question might be 'values' in terms of things that I think are worth striving for, things that I think are beautiful, those are all values.

Where does 'beauty' come from?

Well I think beauty ultimately has to come from the way the brain is set up, so the brain is a devastatingly complicated mechanism. We're only just beginning to understand how it works. And our response to certain things as 'beautiful' must be explicable ultimately in those terms. I hesitate to say that, because some people think that that's in some way to demean it, which of course it isn't - it absolutely isn't. When I am moved to tears as I can be by the slow movement of a Schubert quartet, it is not in any sense to demean that experience, to say that there is nothing going on other than activity in my neurones.

Nonetheless it is one of the sublimest experiences, the experience of Art, profound Art that moves the human spirit, and again we're talking again, and I'm talking now, to the poet in you. And there is a sense in which people - not you - have suggested that there is a scientific way of looking at the world, which runs parallel to say a religious way of looking at the world, or a poetic way of looking at the world, and in some way they all exist at the same time, but don't interrelate. What do you feel about that?

I don't really see how they could not interrelate. I am very suspicious - we keep coming back to this - of uses of words like 'spirit', which I'm happy to use as long as it doesn't suggest anything supernatural or ghostly. To say that something is explicable in terms of the brain, in terms of interactions between neurons, it really is vitally important to understand that that is not to reduce it. It is actually a far more wonderful explanation than just to say 'Oh it's the human spirit'. And the human spirit explains nothing, you've said precisely nothing when you say it's the human spirit.

So are you saying that we undervalue, we haven't yet begun to celebrate, what goes on in our head?

Exactly. We haven't begun to celebrate what goes on in our heads and what goes on in the world, in the universe. These are so much grander, so much more wildly exciting than whatever you can convey by a really rather trite phrase like 'the human spirit', that I just find there's no comparison.

Now you've said that when in terms of biology and genetics of course you are a Darwinian, but in terms of politics and the world and how we live, you are an anti-Darwinian, because you do not believe in the survival of the fittest.

Well I have said that. I believe in the survival of the fittest as an explanation for the evolution of life, but there have been people who have advocated the survival of the fittest as a kind of political creed, where they will justify a form of right-wing politics or economics on the grounds that it conforms to the laws of nature. And that I do object to, as indeed so does any other modern Darwinian. We don't want to see Darwinism being used to justify things like fascism, which it has been.

So is Darwinism over now? Is it are, are we fighting natural selection? Has natural selection come to an end, because we all now use antibiotics and contraceptives and so on?

Well, only in humans. Humans are just a very, very small part of the panoply of life, and it is arguable that in a certain sense, humans have emancipated themselves from Darwinian selection. But it's not over. Darwinism is still THE explanation for the existence of all life, including ourselves, even if just at this moment, we're not indulging in Darwinism or at least indulging it in a rather unusual way.

No, but talk to me then about how man has put a block on Darwinism in his own evolution? Do you believe it's true?

Not sure. I mean if it were true, the way it would come to be true is that we don't die young any more, or it's rather difficult to. That means that most people who want to reproduce do. Whereas in the past, the people who reproduced would be those who made it. And so natural selection was a winnowing process - some survived, some didn't. The ones that survived reproduced and passed on the genes that made them survive. If we live in a welfare state where everybody survives, then there's not the same sense in which genes that make you survive are the ones that get passed on. Any old genes can get passed on, if the welfare state keeps you alive. That would be the point of view that somebody who said that Darwinism had come to an end in humans, somebody who said that - that's what they would say. I'm not sure that I'm going to say that, but that...

But what view do you take of it?

Well, I think there may be more subtle processes of selection going on. Clearly not everybody does reproduce. Some people reproduce a lot more than others. If there is any genetic component to the variants in reproductive success - the word 'success' is a neutral word, a Darwinian word, it doesn't mean that I approve of it - if there is, if you divide those people who have lots of children from those people who have none and then you ask the question 'Is there any statistical tendency for this lot to have a different set of genes statistically from that lot?' [If so], then by definition, we've got natural selection going on. Of course it may be that that particular selection pressure is so short lived in historical time, that it doesn't lead to any interesting evolution - that's what I believe. I mean there could be a selection going on for example, in favour of incompetence in using contraceptives.

If there is a genetic component to incompetence in using contraceptives, then for sure there'll be a slight Darwinian selection pressure in favour of it. I don't really believe that, but that gives you the idea of the kind of thing that might be going on.

As the observance of religion in our particular country has declined, we've seen the rise of perhaps what (laughing) you might call more irrational beliefs. I mean I'm talking about astrology and crystal gazing and things of that kind. It seems perhaps from that, to argue the need for religion, that there is never a vacuum in human ideas, that focus around religious notions.

Yes, that's an interesting point. My prejudice is that those things are even worse than religion. As for whether you're right that they signify a vacuum that needs to be filled, I'm not sure about that. I suppose the human mind is complicated, it has all sorts of desires and things that satisfy it. If there are people who seem to need either religion or astrology and crystal gazing to satisfy them, I would like to have a go at giving them an alternative, and just to see whether perhaps it might work better as a satisfying agent. And that would be understanding of the real world, and understanding of why you exist, where you come from, what the world is, what it's all about.

I think that is such a satisfying thing to have in your head, that I find it very hard to believe that anybody would prefer astrology, crystal gazing, or religion. And so my suspicion is perhaps there is a vacuum that needs to be filled, and it may be that scientific rationalism just hasn't got its act together enough to fill that vacuum, and if it did, it would fill it.

Now you have a position in the humanist society, and we're talking at a time when humanism is coming on the curriculum of schools. Has humanism got it within its vocabulary and its concepts, its narrative, to persuade people?

I'm not sure. Humanism means different things to different people. What is proposed for the national curriculum is I think not just humanism but also atheism was mentioned, and people wondered about how you can teach a negative. I don't have a problem, and I think that a non-theistic understanding of the universe and of life, that's not a religion, but it could very well be taught alongside other religions - which I'm sure will go on being taught - as something deeply satisfying. As something that children will warm to when they will say to themselves 'Ah yes, I understand why I exist, I understand why the world exists.'

What a wonderful place to be in, where you can actually understand why you exist. I would like to see that kind of thing on the syllabus of what is now called RE.

Elsewhere on the web

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.