Local Navigation

Dr. Geoff Bunn devised the 'Mind your Head' exhibition at the Science Museum in 2001 to mark the British Psychological Society's centenary. A discursive psychologist, he is interested in the historical origins and consequences of psychological language terms such as 'soul', 'mind' and 'brain'. His forthcoming book (The Truth Machine: A Social History of the Lie Detector) examines how assumptions about human nature are built into science and technology. He is currently Chair of the British Psychological Society's History & Philosophy of Psychology Section.

My most inspirational historical figure

Memories, Dreams, Reflections by Carl Jung (1965), Cosmos by Carl Sagan (1980), The Arnolfini Portrait (Jan van Eyck, 1434), An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (Joseph Wright of Derby, 1768)

Cave of Forgotten Dreams (Werner Herzog, 2010), Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), Bringing it All Back Home (Bob Dylan, 1965), Ghost in the Machine (The Police, 1981), OK Computer (Radiohead, 1997)

"It weighs around one and a half kilograms and is roughly the size of a small melon."

Dr Kevin Moffat of Warwick University and Dr Richard Baines of Manchester University join Quentin Cooper to discuss how the tiny Drosophila melanogaster, or "fruit fly" is providing scientists with intriguing clues about how the brain works and what happens when it goes wrong. (2008)

Researchers have just finished sequencing the genome of the rhesus macaque monkey, providing brand new insight into how humans are genetically different from our primate relatives. (2007)

The English zoologist and neurophysiologist John Zachary Young explores the function of the brain. He argues that biologists have been concentrating on those features of man that are obviously like those of animals; ie digestion, locomotion and so on. Young argues that the fact that man is a thinking creature, and a worshipping one, is much more significant. (1950)

Watch clips from the recent BBC One series showing how the human brain makes sense of the world.

"How the mind emerges from the brain's breathtaking complexity remains a complete mystery."

Claudia Hammond re-visits the case of Sidney Bradford, born in 1906, who lost his sight when he was 10 months old. When it was finally restored with corneal grafts at the age of 52, a lecturer in Experimental Psychology at Cambridge, Richard Gregory, began a series of tests on SB - a study that would launch Gregory's career as a world-renowned expert in visual perception. (2010)

What governs our perception of the world? And are we correct to distinguish between sight, sound, smell, touch and taste when they appear to influence each other so very much? (2005)

What governs our perception of the world? And are we correct to distinguish between sight, sound, smell, touch and taste when they appear to influence each other so very much? (2005)

We build up a miraculous understanding of the world around us by interpreting the light that enters our eyes. Professor Blakemore explains how the brain interprets these lights to create sight. (1976)

Peter Evans examines how people with nerve or limb injuries may soon be able to command wheelchairs, prosthetics and even paralysed limbs by 'thinking them through' the motions. (2005)

"Each nerve cell can be connected to up to 10,000 others, so at any moment, the brain's neurons are communicating across 100 trillion connections."

Scholars first described the nerves of the human body over two thousand years ago. For 1400 years it was believed that they were animated by 'animal spirits'. In the eighteenth century scientists discovered that nerve fibres transmitted electrical impulses; it was not until the twentieth century that chemical agents - neurotransmitters - were first identified. (2011)

Scholars first described the nerves of the human body over two thousand years ago. For 1400 years it was believed that they were animated by 'animal spirits'. In the eighteenth century scientists discovered that nerve fibres transmitted electrical impulses; it was not until the twentieth century that chemical agents - neurotransmitters - were first identified. (2011)

When a 27 year old man known in the text books simply as HM underwent brain surgery for intractable epilepsy in 1953, no one could have known that the outcome would provide the key to unravelling one of the greatest mysteries of the human mind - how we form new memories. (2010)

When a 27 year old man known in the text books simply as HM underwent brain surgery for intractable epilepsy in 1953, no one could have known that the outcome would provide the key to unravelling one of the greatest mysteries of the human mind - how we form new memories. (2010)

Scientists say they have discovered a "maintenance" protein that helps keep nerve fibres that transmit messages in the brain operating smoothly. (2011)

"When we talk about brain, mind and soul today; or cognition, emotion and the will, or even id, ego and superego, we're using concepts first articulated by the ancient Greeks."

"Hippocrates considered the brain to be the chief organ of control."

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history of ideas about the human brain. Since time immemorial people have puzzled over the brain and its functions.(2008)

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history of ideas about the human brain. Since time immemorial people have puzzled over the brain and its functions.(2008)

The Greek physician Hippocrates, active in the fifth century BC, has been described as the father of medicine, although little is known about his life and some scholars even argue that he was not one person but several. (2011)

The Greek physician Hippocrates, active in the fifth century BC, has been described as the father of medicine, although little is known about his life and some scholars even argue that he was not one person but several. (2011)

Balance and equilibrium in the body is important for many medical traditions. Each tradition understands this balance differently. The idea of the humours emerged in Greece around the 500s or 400s BCE.

"Wherefore the heart and the diaphragm are particularly sensitive, they have nothing to do, however, with the operations of the understanding, but of all these the brain is the cause." (Hippocrates)

In the first Reith Lecture of his series 'Minds, Brains and Science', John Searle, Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, examines the so-called 'mind body problem'. Searle uses this paradox of the conscious mind versus the scientific brain to explore our understanding of the world. (1984)

With what is known as 'Cartesian dualism', Descartes' attempted to address one of the central questions in philosophy, the mind/body problem: is the mind part of the body, or the body part of the mind? If they are distinct, then how do they interact? And which of the two is in charge? (2005)

With what is known as 'Cartesian dualism', Descartes' attempted to address one of the central questions in philosophy, the mind/body problem: is the mind part of the body, or the body part of the mind? If they are distinct, then how do they interact? And which of the two is in charge? (2005)

Compassion for our fellow human beings is something that's long been taught by different faiths and traditions. But could it be used as a tool within therapy to improve mental health? There's a growing interest in compassion-focussed therapy - both for other people and for oneself. It has its roots in the understanding of how the brain evolved. (2011)

"Men ought to know that from nothing else but the brain come joys, delights, laughter and sports, and sorrows, griefs, despondency, and lamentations." (Hippocrates)

In his second Reith Lecture Professor Ramachandran examines the process we call 'seeing'; how we become consciously aware of things around us. How does the activity of the 100 billion little wisps of protoplasm - the neurons in the brain - give rise to all the richness of our conscious experience, including the 'redness' of red, the painfulness of pain or the exquisite flavour of Marmite or Vindaloo? (2003)

In his second Reith Lecture Professor Ramachandran examines the process we call 'seeing'; how we become consciously aware of things around us. How does the activity of the 100 billion little wisps of protoplasm - the neurons in the brain - give rise to all the richness of our conscious experience, including the 'redness' of red, the painfulness of pain or the exquisite flavour of Marmite or Vindaloo? (2003)

For this four-part series, Professor Barry Smith from the Institute of Philosophy, explores the way neuroscience is addressing the ultimate scientific challenge: namely, how our brain makes us the conscious creatures we are - capable of language, thinking and feeling. (2010)

For this four-part series, Professor Barry Smith from the Institute of Philosophy, explores the way neuroscience is addressing the ultimate scientific challenge: namely, how our brain makes us the conscious creatures we are - capable of language, thinking and feeling. (2010)

The analytical facts of science and the imaginative dreamings of art sometimes seem poles apart. But they meet up in the human brain through the process of perception. (2008)

Consciousness has been linked to language, has been married to the mind and divorced from the body; it has been denied to animals, opposed to the subconscious and declared irreducible, but still it defies definition, and the debate rages on as to why we evolved it at all. (2000)

Consciousness has been linked to language, has been married to the mind and divorced from the body; it has been denied to animals, opposed to the subconscious and declared irreducible, but still it defies definition, and the debate rages on as to why we evolved it at all. (2000)

All of us are at it, but no-one feels comfortable talking about it. As you sit there, reading this article, there is something everyone knows about you - you are conscious. (2011)

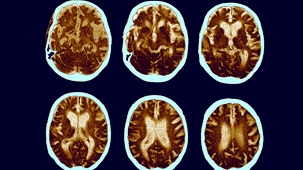

Thanks to the introduction of a range of non-invasive brain imaging techniques, neurosurgical procedures in particular have been revolutionised.

The Renaissance was a period of rebirth for science as well as art. The first treatise of anatomy based on the dissected brain was written at the University of Bologna in 1316. Leonardo da Vinci conducted experiments to discover the anatomy of the brain.

Leonardo Da Vinci's life and interests went way beyond painting. He was an inventor, an architect and a scientist and was especially intrigued by the brain. Dr. Jonathan Pevsner is a neuroscientist at Kennedy Krieger Institute and an expert on the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci. Find out more on his website.

Since time immemorial humanity has been fascinated by genius and geniuses, those extraordinary men and women whose abilities mark them out from the rest of us. Are geniuses born not made, or do they have habits and skills which the rest of use can learn from? Today on Four Thought Andrew poses the question, "What can we learn from Geniuses?" (2011)

Since time immemorial humanity has been fascinated by genius and geniuses, those extraordinary men and women whose abilities mark them out from the rest of us. Are geniuses born not made, or do they have habits and skills which the rest of use can learn from? Today on Four Thought Andrew poses the question, "What can we learn from Geniuses?" (2011)

Is the Renaissance really a cultural miracle, and is it fair to think of medieval thought as being 'obscured by a veil'? Should we even call the period around the fifteenth century the Renaissance when the very word implies that culture, for a thousand years, has been dead? What if our idea of the Renaissance is completely wrong? (2000)

Is the Renaissance really a cultural miracle, and is it fair to think of medieval thought as being 'obscured by a veil'? Should we even call the period around the fifteenth century the Renaissance when the very word implies that culture, for a thousand years, has been dead? What if our idea of the Renaissance is completely wrong? (2000)

Electroencephalography, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and other machines have increased our knowledge of the brain's inner workings.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (FMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) have become essential tools for investigating the brain. Thanks to brain scanning, our knowledge of core physical processes - memory, sight, muscle control - has been hugely improved. But are researchers justified in using these tools to delve into more complex and subjective areas such as emotions, aesthetics and morality? (2009)

Dr Mark Lythgoe investigates the technology of brain scanning. Will this technique ever help people suffering from mental illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia? (2007)

Dr Mark Lythgoe, Director of the Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging, tells the untold story of medical imaging and why uncovering our inner selves changed the world. (2010)

Dr Mark Lythgoe, Director of the Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging, tells the untold story of medical imaging and why uncovering our inner selves changed the world. (2010)

According to popular accounts of neuroscience, we think and act as we do because our brains are "hard wired."

In the first of a new series of Frontiers, Peter Evans discusses new research into vegetative state. Scientists at Cambridge University recently published a paper suggesting that there were "islands" of brain function in the brain of a patient in a vegetative state. Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging, the researchers have shown that the patient's brain apparently responded to spoken instructions. (2006)

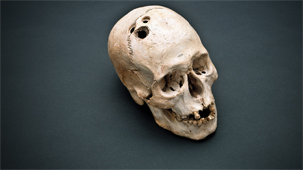

The story of the theft of the skull of composer Joseph Haydn by over-zealous fans, shortly after his death in 1809. Their motivation for stealing the skull was, it is believed, 'scientific': there was at the time a great interest in phrenology, a now-discredited scientific movement that attempted to associate mental capacities with aspects of cranial anatomy. (2010)

If you are 'tone-deaf' can your brain be 're-tuned' by singing lessons? Author and journalist Sathnam Sanghera has spent his life miming to songs. Like one in 15 of us, he believes he is tone deaf. But is he? In this programme he braves both scientific testing and singing lessons in the hope of finding his voice.(2011)

If you are 'tone-deaf' can your brain be 're-tuned' by singing lessons? Author and journalist Sathnam Sanghera has spent his life miming to songs. Like one in 15 of us, he believes he is tone deaf. But is he? In this programme he braves both scientific testing and singing lessons in the hope of finding his voice.(2011)

Almost every organism on Earth has an associated parasite, and most have quite a few. We're used to the idea that influenza and malaria microbes can wreak havoc on our bodies, but researchers now realise how they can also infect our minds, intentionally changing the way we think and behave. (2011)

Almost every organism on Earth has an associated parasite, and most have quite a few. We're used to the idea that influenza and malaria microbes can wreak havoc on our bodies, but researchers now realise how they can also infect our minds, intentionally changing the way we think and behave. (2011)

Ancient treatments for the brain included the gruesome practice of trepanning - literally drilling a hole in the skull. Arabic scholars made significant contributions to the understanding of the brain during the European Dark Ages, focussing on what they called apoplexy.

Surgical treatments for mental disorders in the ancient world centred on the practice of trepanation. The most influential Islamic contributions to knowledge of the brain focussed on the puzzling condition known as apoplexy, which today we would describe as a stroke.

In Episode 1 of Geoff Bunn's series 'A History of the Brain' the focus is on trepanation, the practice of drilling holes in the skull believing that such operations might correct physiological or spiritual problems. Trepanation reveals much about the understanding of the brain from Neolithic to recent times. (2011)

2011 marks a 75th anniversary that many would prefer to forget: of the first lobotomy in the US. This programme tells the story of three key figures in the strange history of lobotomy - and for the first time explores the popularity of lobotomy in the UK in detail. (2011)

2011 marks a 75th anniversary that many would prefer to forget: of the first lobotomy in the US. This programme tells the story of three key figures in the strange history of lobotomy - and for the first time explores the popularity of lobotomy in the UK in detail. (2011)

Dr Mark Porter explores health issues of the day. He visits Glasgow where doctors have pioneered a new treatment for strokes, which is common in older people. They are calling the clot-busting therapy the Lazarus effect because it has such a dramatic result. (2009)

Dr Mark Porter on how best to help people rebuild their lives after a head injury. Damage to the brain affects people in all kinds of ways, both physically and emotionally. At the Bath Neuro Rehabiliation Services, Mark discovers how timely intervention can reduce problems. (2009)

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia. Damaged tissue builds up in the brain and forms deposits called 'plaques' and 'tangles' which cause the cells around them to die. It also affects chemicals in the brain which transmit messages from one cell to another.

The older you get, the more likely you are to get the neurological disease Alzheimer's. But is the ageing process actually causing the disease? Professor Andrew Dillin from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California, used some mice that are genetically programmed to live for a long time to find out. (2009)

The most common type of dementia occurs when brain tissue degeneration causes a progressive deterioration in mental function and ability. It's more likely to develop as people get older, but can affect younger people too. (2011)

Five more genes which increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease have been identified, scientists say. It takes the number of identified genes linked to Alzheimer's to 10 - the new genes affect three bodily processes and could become targets for treatment. (2011)

There are about 40 different types of epilepsy, all with varying symptoms.

Dr Mark Porter discusses epilepsy and its treatment. Mark talks to epilepsy specialists about drug treatments, and a special high-fat diet, known as the ketogenic diet, which helps to reduce the severity of the condition in some children. (2011)

One in every 130 or so of us will develop epilepsy, which isn't one single condition but a cluster of symptoms, all of which result in recurring seizures in the brain. However for such a common disorder Epilepsy is traditionally poorly understood. (2007)

Rolf Harris discusses the life of the Welsh painter Sir Kyffin Williams. Famous for his paintings inspired by the north Wales landscape, Williams never chose to be a painter; he was told by a doctor to take up art for his health when he was diagnosed with epilepsy. (2009)

Rolf Harris discusses the life of the Welsh painter Sir Kyffin Williams. Famous for his paintings inspired by the north Wales landscape, Williams never chose to be a painter; he was told by a doctor to take up art for his health when he was diagnosed with epilepsy. (2009)

Some of the great names in the history of the brain include Thomas Willis, author of a pioneering work on the brain; Pierre Paul Broca, after whom Broca's area in the brain is named; Hans Berger, discoverer of brain waves and William Grey Walter.

On June 13th 1970, the neuroscientist and robotics pioneer, William Grey Walter was seriously injured in a motor scooter accident... The brain scientist had suffered a brain injury.

The Brain's Trust - two archive editions from 1958 and 1961 featuring Dr W. Grey Walter, head of the department of Neuro-Physiology at the Burden Neurological Institute, Bristol. (1958 & 1961)

Roy Plomley's castaway is scientist Dr W Grey Walter. See what choices Dr Grey Walter made to take to his desert island. (1961)

Roy Plomley's castaway is scientist Dr W Grey Walter. See what choices Dr Grey Walter made to take to his desert island. (1961)

A few of the pioneering names in research on the brain, from Thomas Willis in the 17th century through to Colin Blakemore's Reith Lectures of 1976 examining the history of brain studies.

Thomas Willis (27 January 1621 - 11 November 1675) was an English doctor who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology and psychiatry. He was a founding member of the Royal Society. Read the full article at wikipedia

Michael Mosley examines the complex workings of the human brain, starting with a part of the brain known as the BROCA area, which is crucial to speech and language and named after French physician Pierre Paul Broca. (2010)

Professor Blakemore delves into the idea of miraculous mind and explains how the scientific world has not always thought that highly of the brain. (1976)

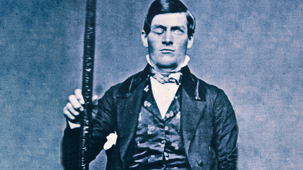

How some unique medical cases changed our understanding of the brain, in particular the remarkable story of Phineas Gage "the American crowbar case".

Phineas Gage was a railway worker in 19th-century Vermont who survived a bizarre accident. A metre-long iron rod shot through his head, changing him and the study of neuroscience forever. (2008)

Phineas Gage was a railway worker in 19th-century Vermont who survived a bizarre accident. A metre-long iron rod shot through his head, changing him and the study of neuroscience forever. (2008)

Nature's Masterpiece: the mechanism of the human brain. An archive programme from 11 January 1949. The programme includes a sequence of features illustrating the similarity of a brain war wound and leucotomy operation; an explanation of the human brain mechanism; developments and discoveries, and future possibilities. (1949)

In the 55 years since Albert Einstein's death, many scientists have tried to figure out what made him so smart. But no one tried harder than a pathologist named Thomas Harvey, who lost his job and his reputation in a quest to unlock the secrets of Einstein's genius.

Select a scientist to explore more about their life, work and inspiration. Choose a subject to discover even more from the Radio 4 Archive & beyond. You can download programmes to listen to later or stack them up to listen to in Your Playlist below.

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.