Beethoven and Ella Milch-Sheriff

Saturday 5 March, 7.30pm

The Bridgewater Hall, Manchester

Welcome to tonight’s performance

Stephen Hough’s recorded Beethoven cycle received universal acclaim on its 2020 release – and we’re thrilled to welcome back the pianist, composer, author and BBC Philharmonic Artist-in-Residence to perform the stormiest of the five piano concertos. This opens a Beethoven-themed concert that continues with the UK premiere of a recent BBC co-commission by Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff: a monodrama inspired by a mysterious dream of migration that Beethoven experienced during a journey to Vienna. The Eternal Stranger is followed by the brooding Funeral March from the ‘Eroica’ Symphony and the ‘Leonore’ No. 3, one of four overtures Beethoven wrote for his only opera, Fidelio.

Our relationship with BBC Radio 3

As the BBC’s flagship orchestra for the North, almost all of the BBC Philharmonic’s concerts are recorded for broadcast on Radio 3. Tonight you will see a range of microphones on the stage and suspended above the orchestra. We have a Producer, Assistant Producer and Programme Manager at the orchestra who produce our broadcasts.

We seek to bring a diverse and risk-taking range of repertoire to our audiences, including our concert-goers here in Manchester, as well as the two million listeners who tune in to BBC Radio 3.

Please do not take flash photographs during the performance as this is very distracting to the artists. Audio and video recording is strictly prohibited.

To ensure that everyone can enjoy the concert, please either turn off your phone and any other electronic devices before it begins or ensure that they are turned to silent.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor 35’

INTERVAL: 20 minutes

Ella Milch-Sheriff

The Eternal Stranger BBC co-commission, UK premiere19’

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, ‘Eroica’ – Funeral march 15’

Overture ‘Leonore’ No. 3 13’

Stephen Hough piano

Eli Danker narrator

BBC Philharmonic

Omer Meir Wellber conductor

Tonight’s concert is being recorded for future broadcast on BBC Radio 3. It will be available to stream or download for 30 days after broadcast via BBC Sounds, where you can also find podcasts and music mixes.

Help us improve our online programmes.

Please take this 5-minute survey and let us know what you think of these notes.

Programme Survey

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 (1800)

1 Allegro con brio

2 Largo

3 Rondo: Allegro

Stephen Houghpiano

This concerto represents a major turning point in Beethoven’s career. Some of its material dates from the late 1790s. Otherwise, it was effectively the composer’s first large-scale orchestral creation of the 19th century. Even more significant than the calendar date is the concerto’s pivotal position in the composer’s own biography. Beethoven was at work on the piece as he began to realise that the problems with his hearing weren’t going to improve – that they were, in fact, likely to lead to complete deafness.

That realisation had a cataclysmic effect on Beethoven as a person and shot entirely new sentiments and concepts into his music, starting with this piece. One of the most obvious implications of his impending deafness was his potential inability to perform and improvise on-stage with an orchestra.

Beethoven got wise to that new reality in this piece. The solo piano part in the Third Concerto is more clearly defined, on the page, than in its predecessors. The soloist takes on a more individual, imposing and energetic role. Cadenzas – the passages in which the soloist would traditionally improvise to demonstrate their prowess – are written out in full, instructions for future pianists to obey to the letter long after Beethoven himself could no longer perform.

The pianist’s more controlling role is also felt in the first movement’s coda, its ‘last word’. Here, the soloist plays along with the orchestra – a strikingly presumptuous act with only one tentative precedent in a concerto by Mozart.

That particular Mozart concerto (No. 24, K491) looms large over many aspects of Beethoven’s Third. Both use the tempestuous key of C minor and both exploit the ‘minor-keyness’ with an opening tune based on the interval of a minor third.

That said, the feelings of heroic conflict and tension in Beethoven’s score were entirely new. Here, the piano initiates a stand-off against the orchestra in a manner unusual even for this composer. Major keys tussle with minor ones throughout the opening movement, marked Allegro con brio (‘fast and with spirit’).

In the slow middle movement, Beethoven reaches for expressive tools that look forward to the full flowering of Romanticism. The music’s meditative qualities conjure a picture of the composer clinging on dearly to music’s beauty, as if he sensed that soon he’d be unable to hear it.

Beethoven knew that his audience in 1803 Vienna expected a gregarious final send-off. The main tune of the finale – heard initially on the piano, before transferring immediately to the oboe – sounds impish and witty but actually stretches over a whole eight bars. It is the longest tune in any Beethoven concerto – fitting for a score that radically changed the dimensions of the genre..

Programme note © Andrew Mellor

Andrew Mellor is a journalist and critic based in Copenhagen, where he writes for national and international publications. His book The Northern Silence – Journeys in Nordic Music and Culture will be published in June (Yale UP).

Ludwig van Beethoven

In his early twenties Beethoven left his native Bonn for Vienna, where he became established in fashionable circles as a composer, piano virtuoso and improviser. Largely following the Classical models of Haydn and Mozart in his ‘early’ period, he recognised signs of his impending deafness as early as 1796. In 1802 he revealed his suffering and alienation, as well as a creative resolve, in his Heiligenstadt Testament. His middle period was characterised by a broadening of form and an extension of harmony to suit his proto-Romantic expression, spawning the Symphonies Nos. 2 to 8, notable piano sonatas, several string quartets and his only opera, Fidelio. From 1812 to 1818 he produced little music, but his last years saw the mould-breaking ‘Choral’ Symphony, and an exploration of increasing profundity in the more intimate mediums of the string quartet and piano sonata.

Profile by Edward Bhesania © BBC

INTERVAL: 20 minutes

Ella Milch-Sheriff (born 1954)

The Eternal Stranger (2020)

BBC co-commission: UK premiere

Eli Dankernarrator

When conductor Omer Meir Wellber (to whom this piece is dedicated) approached me with the idea of writing a work connected in some way with Beethoven’s life – to mark the composer’s 250th anniversary in 2020 – I was almost paralysed at the prospect. How could it be done? In what way could I ever ‘touch’ Beethoven’s life story?

It all started with Beethoven’s curious and relatively unknown dream, about which he wrote from Baden in a letter dated 10 September 1821 to his friend and publisher Tobias Haslinger.

Beethoven dreamt of undertaking a journey ‘to no less distant a country than Syria, then to India, back again, even to Arabia; finally I reached Jerusalem’. There, he encountered some kind of religious experience and his friend Tobias appeared. Beethoven described a musical canon he heard in his dream and he wrote this out in his letter to Tobias, even using his friend’s name as lyrics to the music.

This strange dream inspired the Israeli playwright and author Joshua Sobol to write a long poem on this topic, which inspired me to compose The Eternal Stranger. I chose those parts from the text that enabled me to present a situation in which a person – not necessarily a refugee, although it could be – finds themselves in an unknown and hostile environment.

Who is the ‘stranger’ in this work? Is it Beethoven, who was considered by Viennese society to be a genius but half-crazy, dirty and disgusting? He was rejected by all but his faithful close friends. Being deaf only emphasised Beethoven’s strangeness and loneliness. Or is it a refugee, any refugee, who had a full life somewhere else but had to escape and finds themselves in a totally different culture, not able to communicate with people?

I leave the question open. The stranger is anyone who finds him- or herself in a hostile environment with no legitimate reason to be rejected other than the fact that he or she is different – looks different, moves differently, speaks differently. In any case, the stranger is a human being who has the same desires as everyone else.

This is a work about loneliness and strangeness but also about the desire for life.

Beethoven’s amazing dream enabled me to draw on the vast musical connotations from my home country of Israel and the sounds of my childhood – a mixture of Arabic music, Jewish music of all kinds (Eastern and Western) as well as references to Vienna (the old European world) and even Mahler and Schoenberg, both of whom encountered anti-Semitism.

Beethoven’s own music makes an appearance in the piece, especially in the first part, modified in various ways. It is mixed with Middle-Eastern sounds to create two completely different worlds that meet but perhaps fail to connect at all.

In his text, Joshua Sobol alternates between the first person, second person and third person. His ‘stranger’ has a shadow and this shadow is spoken of in the third person. The ‘third person’ is a part of the stranger’s identity that cannot be defined. At times the stranger experiences an inability to communicate with anyone, a terrible loneliness. Life becomes still. He cannot make sense of words and everything sounds like a collection of noises. (This experience could also be associated with Beethoven’s deafness.) Language, the primary mode of communication between people, eludes him. But the language of the body is stronger and it gives him life and hope.

I am deeply grateful to my late husband, the composer-conductor Noam Sheriff who, two weeks before his sudden death, introduced me to Beethoven’s extraordinary dream, which became the key inspiration for this work.

Programme note © Ella Milch-Sheriff

Ella Milch-Sheriff

Most prodigious composers have musical parents to thank for their youthful success, but not Ella Milch-Sheriff. ‘Nobody played at home’, she says, ‘it was my initiative to start playing and composing.’ Milch-Sheriff grew up in Haifa, Israel, where she remembers being exposed to ‘European music, everything from Bach onwards, but also to Israeli pop and Arabic music. Everything came together into what I now compose.’ Her style is as rich and distinctive as these multifarious influences suggest, blending Western orchestral textures and timbres with evocative fragments of Middle Eastern melodies. It is hypnotic, alluring and highly unique.

As a singer herself, she is drawn to composing for the voice and has a string of highly acclaimed operas to her name. These include her semi-autobiographical chamber opera Baruch’s Silence (2010), and And the Rat Laughed (2005), which is based on Israeli author Nava Semel’s book of the same name and earned her Israel’s Rosenblume Prize. The Eternal Stranger, receiving its first UK performance tonight, was premiered by the Gewandhaus Orchestra as part of the Beethoven 250 celebrations. It reveals a more absurdist side to Milch-Sheriff’s style, which above all is rooted in compelling storytelling.

Profile © Jo Kirkbride

Jo Kirkbride is Chief Executive of the Edinburgh-based Dunedin Consort and a freelance writer on classical music. She studied Beethoven for her PhD.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55, ‘Eroica’ (1803) –Funeral March

When Beethoven published his Symphony No. 3 in 1806, he dedicated it simply to ‘the memory of a great man’. But the mysterious, unnamed individual is really no mystery at all: it is well documented that Beethoven had originally intended to honour Napoleon, whose life and legacy are described over the course of its four movements. As it was, Beethoven withdrew the attribution before publication upon hearing that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor, revising his opinion of a man he had idolised to a ‘tyrant’, no more than a ‘common mortal’.

As a symphony the ‘Eroica’ is longer, more complex and more surprising than anything Beethoven had unleashed on his public up to that point. It tracks a progression from the grand ambition and heroic struggles of the opening Allegro, through to a celebratory finale, which sounds a note of hope for change, the brilliant new aftermath of the revolution.

One of the symphony’s many surprises is its second movement, a solemn Funeral March which seems to offer a projection of Napoleon’s death when the symphony has barely begun. It presents a picture of mourning on a grand and hugely moving scale, erupting at its centre into some of the most joyous music Beethoven ever composed. Is he rejoicing in Napoleon’s death? Or in the closing of one historical chapter and the glorious birth of the next.

Programme note © Jo Kirkbride

Ludwig van Beethoven

Overture ‘Leonore’ No. 3, Op. 72b (1806)

In all of Beethoven’s output, nothing was subject to quite the same torturous process of composition as his only opera. ‘Of all my children, this is the one that cost me the worst birth-pangs and brought me the most sorrow’, he later lamented to his biographer, ‘and for that reason it is the one most dear to me.’ Fidelio, as the opera would eventually become known, began life as Leonore in 1803. But the three-act Leonore (originally named after the heroine) was subsequently revised and reduced into the two-act Fidelio (‘the faithful one’), and was not premiered in its final version until 11 years later.

The overture, meanwhile, appeared in no fewer than four separate versions, of which the second incarnation – confusingly now known as ‘Leonore’ No. 3 – seems to have earned its place as the concert hall favourite. While the fourth and final Fidelio overture would take themes from the opera and use them to create a chronological précis of the opera’s main dramatic action, the Overture No. 3 was composed as a dramatic curtain-raiser in its own right. Indeed, its tone is so dramatic that it risks overshadowing the opera itself, hence its more fitting place in the concert hall.

The overture begins morosely and in darkness in Florestan’s prison cell, his thoughts gradually drifting towards happier, earlier, happier times. As minor turns to major and Florestan’s fighting spirit returns, the overture unfurls to become a buoyant work of irrepressible energy, a triumph of liberty in the face of adversity, the epitome of Beethoven’s ‘heroic’ style.

Programme note © Jo Kirkbride

Biographies

Omer Meir Wellber conductor

Omer Meir Wellber has established himself as one of today’s leading conductors, equally at home in operatic and orchestral repertoire. He currently divides his time between his positions of Chief Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic, Music Director of the Teatro Massimo Palermo, Principal Guest Conductor at the Semperoper Dresden and Music Director of the Raanana Symphonette in Israel. In September this year he takes up the position of Music Director at the Vienna Volksoper as Lotte de Beer becomes Director, marking a new era for the opera house.

He has worked with some of the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Israel and London Philharmonic orchestras, Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, Berlin Radio, City of Birmingham, SWR and Swedish Radio Symphony orchestras, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Dresden Staatskapelle and Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra.

His close ties to his native Israel are evident in his collaboration with the Raanana Symphonette, with whom he works closely on music education projects. He also collaborates with a number of institutions through outreach programmes and fosters the next generation of young conductors through educational lectures.

Omer Meir Wellber made his literary debut with his novel Die vier Ohnmachten des Chaim Birkner, published by BerlinVerlag in 2019. It tells the story of Chaim Birkner, a tired and broken man who is forced by his daughter to face life one last time. Last year it was published in Italian by Sellerio Editore and it will also be published in French by Éditions du sous-sol.

Stephen Hough piano

Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Photo: Sim Canetty-Clarke

Stephen Hough has been named by The Economist as one of Twenty Living Polymaths and combines a distinguished career as a pianist with those of composer and writer. He was the first classical performer to be awarded a MacArthur Fellowship and was made a CBE in the 2014 New Year’s Honours.

This season he performs with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Dortmund, London and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic orchestras, Atlanta, BBC and Dallas Symphony orchestras and Tonkünstler Orchestra. He is the BBC Philharmonic’s 2021/22 Artist-in-Residence, and this year returns to the Far East to perform with the Singapore Symphony Orchestra, among others. Recent concerto highlights include engagements with the New York and Royal Philharmonic orchestras, Minnesota Orchestra, City of Birmingham, Finnish Radio, Toronto and Vienna Symphony orchestras and the Philharmonia.

He is a regular guest at festivals such as Salzburg, Mostly Mozart, Edinburgh, La Roque d’Anthéron, Aldeburgh and the BBC Proms, having made his 29th appearance at the latter with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in 2020. In June 2020 he returned to Wigmore Hall to give the UK’s first live classical music concert in a major venue since the nationwide lockdown earlier that year. Recital highlights this season include a return to London’s Royal Festival Hall as well as to Caramoor, Toronto, Tallinn, Gstaad and the Bridgewater Hall.

His extensive discography has garnered major international awards, including the Diapason d’Or de l’Année, several Grammy nominations, and eight Gramophone Awards, including Record of the Year and the Gold Disc. Recent releases include Beethoven’s complete piano concertos with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Hannu Lintu.

His recent compositions include a string quartet for the Takács Quartet and the commissioned work for this year’s Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, to be performed by all 30 competitors in May/June.

As an author, he saw his collection of essays Rough Ideas: Reflections on Music and More, published in 2019, win a 2020 Royal Philharmonic Society Award and be named one of Financial Times’ Books of the Year 2019. His first novel, The Final Retreat, was published in 2018.

He is a Visiting Professor at the Royal Academy of Music, the International Chair of Piano Studies at the Royal Northern College of Music and is on the faculty of The Juilliard School in New York.

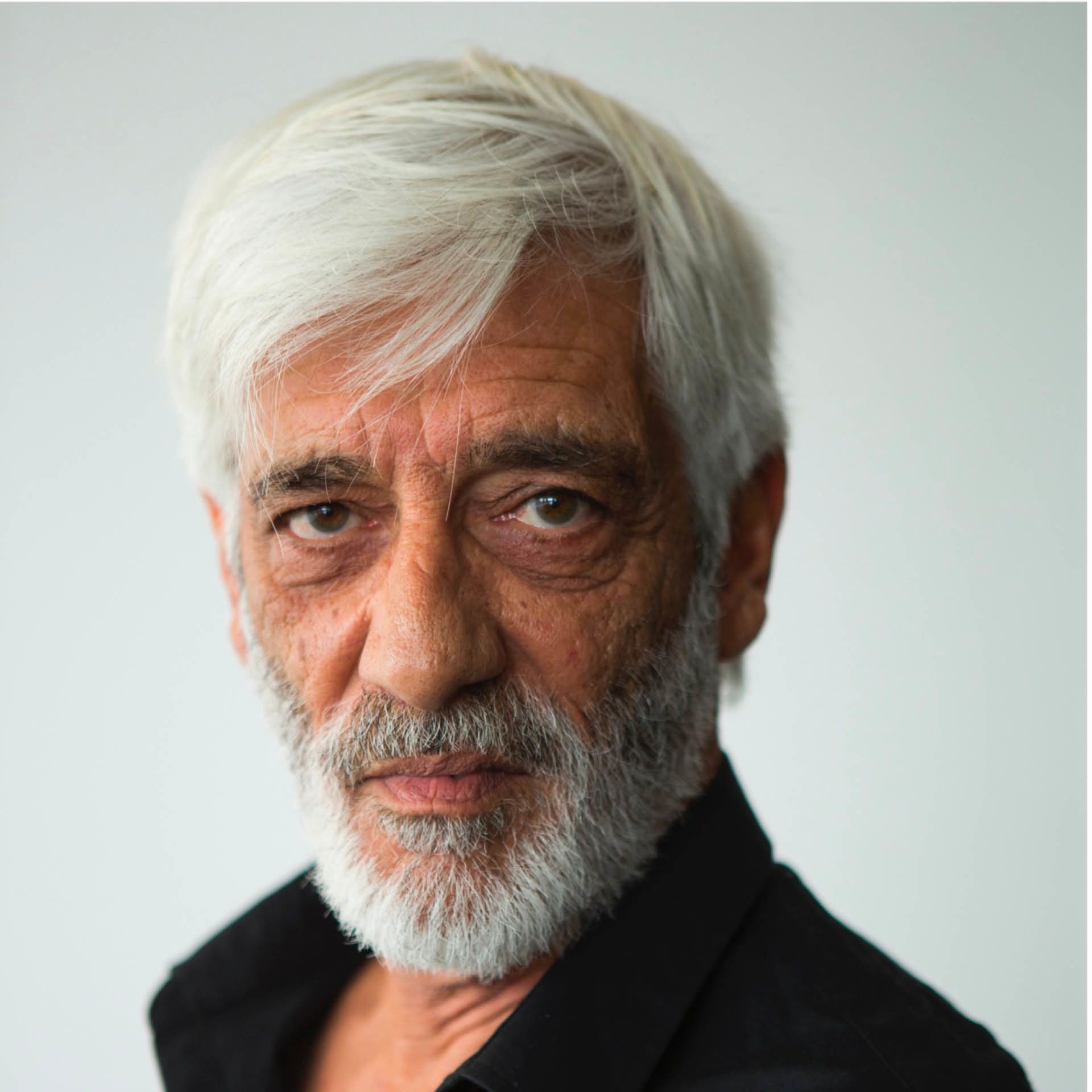

Eli Danker narrator

Photo: Maya Lusky

Photo: Maya Lusky

Eli Danker is an Israeli stage actor whose work moves between the world of theatre in Israel and Hollywood. After studying at the Beit Zvi drama school in Israel, he continued his studies in New York. Having returned to Israel, he joined the Khan Theatre in Jerusalem.

His abilities as a pianist and singer have opened up a wide artistic spectrum for him and enabled him to take on a broad range of roles. Among others, he has played Rogozhin in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, Collie Crouch in Brecht’s In the Jungle of Cities, the Horse in Kästner’s The 35th of May, or Conrad’s Ride to the South Seas and Dumbo in Heller’s Catch 22.

While a member of Habimah, the Israeli National Theatre, he played Jason in Medea and Mortimer in Maria Stuart. He also studied pantomime at the École Jacques Lecoq.

He has worked in opera and for film and television, too, most recently in Viktor, with Gérard Depardieu, and the American TV series 24: Legacy. He is currently a member of the ensemble of the Cameri Theatre in Tel Aviv, where he most recently appeared as the Cook in Mother Courage.

He previously collaborated with Omer Meir Wellber as the narrator in Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, as well as in the world premiere of Ella Milch-Sheriff’s The Eternal Stranger in February 2020.

BBC Philharmonic

The BBC Philharmonic is reimagining

the orchestral experience for a new generation – challenging perceptions, championing innovation and taking a rich variety of music to the widest range of audiences.

The orchestra usually performs around 100 concerts every year, the vast majority of which are broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Along with around 35 free concerts a year at its MediaCityUK studio in Salford and a series of concerts at Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall, the orchestra performs across the North of England, at the BBC Proms and internationally, and records regularly for the Chandos label.

The BBC Philharmonic’s Chief Conductor is Omer Meir Wellber. Described by The Times’s Richard Morrison as ‘arguably the most inspired musical appointment the BBC has made for years’, Israeli-born Wellber burst into his new role at the 2019 BBC Proms and has quickly built an international reputation as one of the most exciting young conductors working today. The orchestra also has strong ongoing relationships with its Chief Guest Conductor John Storgårds and Associate Artist Ludovic Morlot. In May last year the orchestra announced young British composer and rising star Tom Coult as its Composer in Association.

The scope of the orchestra’s programme extends far beyond standard repertoire. Over the past few years it has collaborated with artists as varied as Clean Bandit, Jarvis Cocker and The Wombats; played previously unheard music by writer-composer Anthony Burgess in a unique dramatisation of A Clockwork Orange; joined forces with chart-toppers The 1975 at Blackpool’s Tower Ballroom; premiered The Arsonists by composer Alan Edward Williams and poet Ian McMillan, the first opera ever written to be sung entirely in a Northern English dialect; and broadcast on all seven BBC national radio networks, from BBC Radio 1 to BBC Radio 6 Music and the BBC Asian Network. Last year the orchestra also entered the UK Top 40 singles chart with ‘Four Notes: Paul’s Tune’.

The BBC Philharmonic is pioneering new ways for audiences to engage with music and places learning and education at the heart of its mission. Outside of the concert hall, it is passionate about taking music off the page and into the ears, hearts and lives of listeners of all ages and musical backgrounds – whether in award-winning interactive performances, schools’ concerts, Higher Education work with the Royal Northern College of Music or the creation of teacher resources for the BBC’s acclaimed Ten Pieces project. Through all its activities, the BBC Philharmonic is bringing life-changing musical experiences to audiences across Greater Manchester, the North of England, the UK and the rest of the world.

First Violins

Yuri Torchinsky Leader

Midori Sugiyama Assistant Leader

Thomas Bangbala Sub Leader

Alison Fletcher *

Kevin Flynn †

Martin Clark

Karen Mainwaring

Catherine Mandelbaum

Anya Muston

Robert Wild

Toby Tramaseur

Ian Flower

Second Violins

Lisa Obert *

Lily Whitehurst

Gemma Bass

Lucy Flynn

Christina Knox

Rebecca Mathews

Claire Sledd

Matthew Watson

Oliver Morris

William Chadwick

Violas

Tim Pooley §

Bernadette Anguige †

Kathryn Anstey

Alexandra Fletcher

Nicholas Howson

Roisin Ni Dhuill

Fiona Dunkley

Amy Hark

Cellos

Peter Dixon *

Maria Zachariadou ‡

Steven Callow †

Jessica Schaefer

Rebecca Aldersea

Melissa Edwards

Elinor Gow

Miriam Skinner

Marina Vidal Valle

Elise Wild

Double Basses

Ronan Dunne *

Alice Durrant †

Miriam Shaftoe

Andrew Vickers

Ben Burnley

Flutes

Alex Jakeman *

Victoria Daniel †

Piccolo

Jennifer Hutchinson

Oboes

Rainer Gibbons §

Kenny Sturgeon

Cor anglais

Gillian Callow

Clarinets

John Bradbury *

Daniel Bayley

Bass Clarinet

Daniel Bayley

Bassoons

Roberto Giaccaglia *

Angharad Thomas

Contrabassoon

Bill Anderson

Horns

Ben Hulme *

Phillip Stoker

Tom Kane

Jonathan Barrett

John Thornton

Trumpets

Jason Lewis §

Gary Farr †

Simon Cox

Trombones

Richard Brown *

Gary MacPhee

Bass Trombone

Mark Frost

Timpani

Paul Turner *

Percussion

Paul Patrick *

Geraint Daniel

* Principal

† Sub Principal

‡ Assistant Principal

§ Guest Principal

¥ Associate Principal

The list of players was correct at the time of publication

Director

Simon Webb

Orchestra Manager

Tom Baxter

Assistant Orchestra Manager

Stefanie Farr/Beth Wells

Orchestra Personnel Manager

Helena Nolan

Orchestra Administrator

Maria Villa

Senior Producer

Mike George

Programme Manager

Stephen Rinker

Assistant Producer

Katherine Jones

Marketing Manager

Amy Shaw

Marketing Executive

Jenny Whitham

Marketing Assistant

Kate Highmore

Manager, Learning and Digital

Jennifer Redmond/ Beth Wells

Project Co-ordinator, Learning

Youlanda Daly/ Róisín Ní Dhúill

Librarian

Edward Russell

Stage Manager

Thomas Hilton

Transport Manager

Will Southerton

Team Assistant

Diane Asprey

Keep up to date with the

BBC Philharmonic

Listen to our BBC Radio 3 broadcasts via the BBC Sounds app. Visit our website and follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram and sign up to the newsletter

To help us improve our online concert programmes, please take this 5-minute survey

Produced by BBC Proms Publications