Home > Features > What was so special? The legacy of blind school

What was so special? The legacy of blind school

8th June 2005

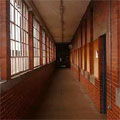

For those of us who attended them, their names echo in our lives like the sound of iron falling on to concrete: Lickey, Bristol, Dorton, Benwell, Vinnie's, Tapton Mount, Wavertree, Lindon, Bridgend.

The Dickensian regimes of these old-fashioned blind boarding schools lived on well past their sell-by date. They shaped - some might say blighted - the lives of those of us who were educated at these establishments.

Although the schools were scattered round the country - from Bristol to Newcastle, from Sheffield to South Wales - and although they might have had their differences and changed over the years, it's amazing how much of what they shared lives on in the collective memory. What starts out as personal anecdote transfers easily into shared experience.

I went to the same school as my mother. She'd been there some twenty years earlier. Many of my teachers had taught her, and the same headmaster was still in charge. The walls were the same brown and cream they'd been in her day.

Although the schools were scattered round the country - from Bristol to Newcastle, from Sheffield to South Wales - and although they might have had their differences and changed over the years, it's amazing how much of what they shared lives on in the collective memory. What starts out as personal anecdote transfers easily into shared experience.

I went to the same school as my mother. She'd been there some twenty years earlier. Many of my teachers had taught her, and the same headmaster was still in charge. The walls were the same brown and cream they'd been in her day.

The memories of my first day at school are clearer in my mind than some of the memories of what happened last week. My fifth birthday was on a Sunday that year, so I must have started school on Monday 6 May. I can remember the name of the woman in the white coat who kept asking my mother if she was sure I didn't wet the bed: she was called Miss Bennett. I can remember the point at which my parents left and how I screamed after them. I can remember the smell of bread and butter in the dining room. And I can remember that they put us to bed at half past five on a warm Spring evening.

But ridiculously early bed-times would turn out to be the least of our worries (although, funnily, it's one of the things that almost everyone who went to one of these places mentions with real resentment). The regime at the school I attended went beyond austerity and was, in many senses, just plain cruel. I can't entirely recall why I was regularly caned during the first two years I was there, but I'm pretty sure that it was for nothing more than talking in the dormitory during the designated time for silence, which could start as early as six o'clock in the evening.

As well as the physical punishment, there was the mental anguish of spending night-times anticipating and dreading what was to come the next day. I can remember one particular morning, though, when I woke up having forgotten about my imminent caning. It was a member of the 'care' staff - unsurprisingly we didn't call them that - who reminded me: "Don't know what you've got to be so cheerful about, Macrae".

Another shared memory for people who went to special school is the experience of punishment by isolation. When everything you do - including eating, bathing and going to the toilet - is shared with dozens of fellow pupils 24 hours a day, the feeling of being alone and away from institutional security brings added terror. Someone told me recently about having been put in what was effectively a cupboard, whilst my solitary confinement was served out in an attic room with a tiny skylight window, at which birds would come and peck.

Did the staff ever imagine what such punishments did to the mind of an eight year-old child?

But ridiculously early bed-times would turn out to be the least of our worries (although, funnily, it's one of the things that almost everyone who went to one of these places mentions with real resentment). The regime at the school I attended went beyond austerity and was, in many senses, just plain cruel. I can't entirely recall why I was regularly caned during the first two years I was there, but I'm pretty sure that it was for nothing more than talking in the dormitory during the designated time for silence, which could start as early as six o'clock in the evening.

As well as the physical punishment, there was the mental anguish of spending night-times anticipating and dreading what was to come the next day. I can remember one particular morning, though, when I woke up having forgotten about my imminent caning. It was a member of the 'care' staff - unsurprisingly we didn't call them that - who reminded me: "Don't know what you've got to be so cheerful about, Macrae".

Another shared memory for people who went to special school is the experience of punishment by isolation. When everything you do - including eating, bathing and going to the toilet - is shared with dozens of fellow pupils 24 hours a day, the feeling of being alone and away from institutional security brings added terror. Someone told me recently about having been put in what was effectively a cupboard, whilst my solitary confinement was served out in an attic room with a tiny skylight window, at which birds would come and peck.

Did the staff ever imagine what such punishments did to the mind of an eight year-old child?

Over the years, everyone I've spoken to or heard from on the subject of blind schools has had one particular person they remember with real hate or lasting fear. For me, it was a woman called Miss Lynne. As a child I had a pretty sunny disposition and took life as it came, but she turned me into a jumpy, distressed and terrified thing who began to doubt that he had any worth at all. Most of what Miss Lynne did to me was psychological; she never missed an opportunity to tell me that I was filthy and worthless like the rest of my snotty-nosed guttersnipe family. Still, at least she couldn't get me on the bed-wetting, which was just as well. There was one boy who was an almost daily bed-wetter, and Miss Lynne's way of showing her displeasure was to literally rub his nose in it. Of course, his terror at the prospect of this happening again virtually ensured that he carried on wetting the bed every night.

Looking back, the abuse I suffered was comparatively mild when I consider what could have happened - and what did happen to more vulnerable children.

But what impact have my school experiences had on how I've lived and how I am now? I'm not talking here about the benefits I've had from a reasonable education, nor that I'm still teaching myself not to parent in the way that the school parented me. No, the impact lies in the psychological reverberations, the deep insecurities and the frightening and continuing anxieties that no amount of material success or current happiness will ever dislodge.

Looking back, the abuse I suffered was comparatively mild when I consider what could have happened - and what did happen to more vulnerable children.

But what impact have my school experiences had on how I've lived and how I am now? I'm not talking here about the benefits I've had from a reasonable education, nor that I'm still teaching myself not to parent in the way that the school parented me. No, the impact lies in the psychological reverberations, the deep insecurities and the frightening and continuing anxieties that no amount of material success or current happiness will ever dislodge.

More articles about

Bookmark with...

Live community panel

Our blog is the main place to go for all things Ouch! Find info, comment, articles and great disability content on the web via us.

Listen to our regular razor sharp talk show online, or subscribe to it as a podcast. Spread the word: it's where disability and reality almost collide.

Comments