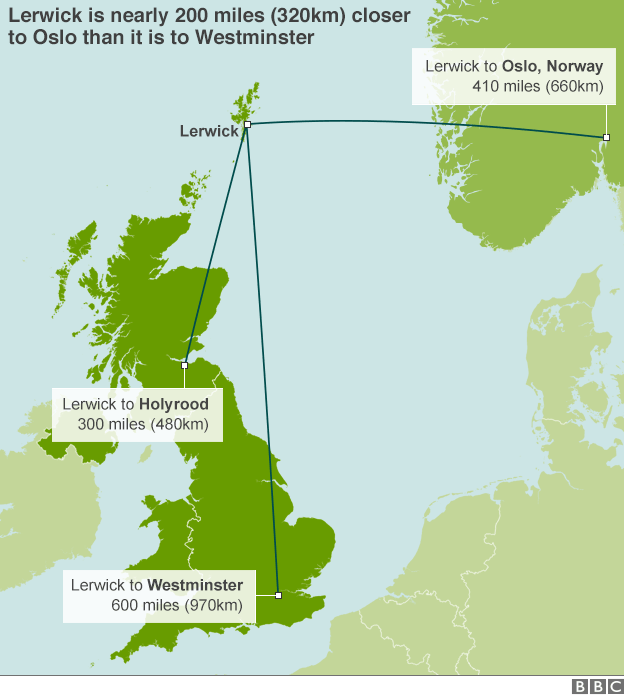

Orkney and Shetland is the most northerly parliamentary constituency in the UK. It's further north than Moscow, and closer to Oslo than it is to Westminster. So do islanders feel like they are taking part in the same general election?

Stand beneath the swirling seagulls in the harbour of the Shetland islands' only town, and the UK's most northern constituency could hardly feel any more remote from Westminster, some 600 miles (960km) south.

Rugged coastlines and wind-scalloped hills stretch into the distance. Fishing boats and ferries come and go. A huge ferry that is a temporary home to hundreds of oil workers is moored by the pier.

It feels a far cry from the formal setting of the House of Commons, with its lofty oratory and rowdy shouting matches.

Nowhere in Shetland - which is made up of more than 100 islands, of which 15 are inhabited - is more than three miles (5km) from the sea.

Orkney, which comprises about 70 islands, 20 of which are inhabited, is similarly coastal.

Distances measured as the crow files and sourced using Google maps. Figures rounded to nearest 10 miles

But the constituency of Orkney and Shetland isn't just geographically distant from the heart of UK government. Culturally it's a world apart, too.

A historic hub of Viking expansion, Shetland still feels very Nordic.

Lerwick's buildings and boathouses have Scandinavian influences. Shetland flags - blue and white like the Scottish saltire, but with a Scandinavian-style cross - flutter in the wind.

Speak to a local, and it's clear Shetlanders feel they have their own identity. "I've been here since I was 16, but I don't count as Shetlander," says 82-year-old Rita, who used to be at the helm of a fishing business that has been in the family for about 300 years.

She feels like the constituency is largely ignored by Westminster. "You don't see politicians like Mr [David] Cameron unless there's an accident or the price of oil is fluctuating, that's the way I feel," she says.

Her daughter Gina, who now runs McNabb Kippers, thinks politicians don't really understand what life is like in the Shetland Islands.

"It's different - there's no hustle and bustle up here. But it's a working island," she says.

Gina McNabb and mother Rita, who own a fishing business, feel largely ignored by Westminster

The family fishing business has been in the Shetland Islands for 300 years

Up the road on the high street, baker Cherl Maclennan, who owns Fine Peerie Cakes and describes herself as a "true blue Shetlander", agrees.

"I think we have a unique problem, given the distance we are from the decision-makers in London. We are very remote, the cost of getting on and off the island is everyone's biggest bugbear. They don't take that into consideration," she says.

For many residents, getting off the Shetland Islands involves getting the overnight ferry to Aberdeen from Mainland, the Islands' biggest island. That takes 12-13 hours alone. There is also the option of flying to Aberdeen and airports such as Manchester.

Bressay island is home to around 350 people, many of whom commute to Lerwick daily

There are other factors that make the Shetland Islands stand out as unusual.

Being surrounded by rich fishing grounds and oil and gas fields has meant many Shetlanders have shared in the islands' fortune. Shetland's fishing industry, which is its biggest sector, is worth well over £200m a year. The presence of oil is worth over £100m a year, not counting the value of the oil itself, according to Visit Shetland.

Unemployment is significantly lower in the constituency than the rest of the UK. Nearly 72% of residents aged 16-74 are in employment, compared with a UK average of 61.6%, according to the House of Commons Library, external. Working-age residents claiming out-of-work benefits stands at 0.8%, compared with a UK average of 2.7%.

And in constituency terms, the electorate is smaller than most. Orkney and Shetland has an electorate of 33,085, compared with the national average seat size of 70,216.

But not everyone in Lerwick feels that life is fundamentally different. Audrey Alfa, 80, moved to the Shetland Islands from Herefordshire just over two years ago and hasn't noticed much of a difference in people's priorities.

"Everyone wants enough money to live on," she says.

While London is indisputably a long way away, a majority in the constituency voted against the seat of central government being moved closer to home.

Shetland rejected independence by 64% to 36% last September, with a turnout of 83.7%. Orkney, which is a separate constituency in the Scottish Parliament, also voted against independence, by 67% to 33%, with exactly the same turnout. That compared with a national picture which saw Scotland vote against independence 55% to 45%, with a turnout of 84.59%.

Born-and-bred Shetlander Andrea Groat, 47, who is a part-time carer and mother, voted Yes to independence, believing it would bring the government closer to the people of the Shetland Islands. "I'm more inclined to listen and get involved in Scottish Parliament. I do listen if it's relevant in Westminster, but not as much," she says.

By contrast, Kayla Chancton, 23, who has worked at Anderson knitwear since the age of 13, voted No. "I didn't see any benefit - we've all got the same issues, it just takes a bit more time for things to filter through to here," she says. "We still have poor folk and wealthy ones."

Kayla Chancton thinks the Shetland Islands are affected by the same issues as everywhere else

Shetlander Andrea Groat, 47, says Holyrood feels less remote than Westminster

The islands attracted special attention during the referendum campaigns, with both the "Yes" and "No" side making attempts to appeal to the islands by promising them more powers in the wake of a joint declaration by the island councils, which included a call for control over seabed revenues.

There was even a local campaign for the islands to have their own referendum, which failed to gain support from Shetland's political leaders.

Orkney and Shetland is used to feeling unique, and it is also distinctive in general election terms. While not a single Scottish seat changed hands in 2010, this constituency has shown remarkable fealty to the Liberal Democrats and their predecessors the Liberals, staying with the party at every election since 1950.

But political certainties in Scotland are crumbling. Pollsters have observed a surge of support for the SNP, and it's been suggested that the party could win every seat in Scotland, external.

It's not just Labour heavyweights like Jim Murphy and Douglas Alexander who are threatened - polls have suggested, external senior Lib Dems like former party leader Charles Kennedy and Danny Alexander, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, could lose their seats, too, following a collapse in support for the Lib Dems across the board.

More from the Magazine

The long history of Viking and Norse settlement in Scotland has left an indelible mark. "In countries where it's dark half the year, you do tend to have a great tradition of storytelling," says the author Ian Rankin. "Whenever I've met Scandinavian writers, we do share quite a dark sense of humour and a feeling that the world's messed up, we might as well laugh about it.

Polling expert John Curtice of the University of Strathclyde says Orkney and Shetland is probably the safest Lib Dem seat in the whole of the UK. "If the SNP manage to pick up Orkney and Shetland then as far as the Lib Dems are concerned, it's a complete disaster. The constituency was one of the places that kept the old Liberal party alive in the 1950s when it was at absolute rock bottom, down at 2.5% of the UK vote.

"Frankly it's one of the few beacons of Liberal Democrat light, and they will be very keen to keep it alight," he says.

Kayla Chancton puts the long Liberal Dem run down to Shetlanders being "stuck in their ways".

Rita McNabb thinks the constituency is still voting for Jo Grimond, the Liberal Party leader who represented the seat between 1950 and 1983. "He was good for the island, and people haven't forgotten that," she says.

An oft-repeated tale has Mr Grimond being asked to give the name of his nearest rail station on a parliamentary expenses form, and writing "Bergen, Norway".

That's a long, long way from London.

The candidates for the constituency are:

Donald Cameron (Conservative)

Alistair Carmichael (Liberal Democrat)

Gerry McGarvey (Labour)

Danus Skene (SNP)

Robert Smith (UKIP)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.