The Bank of England is increasingly signalling that interest rates will soon begin to rise

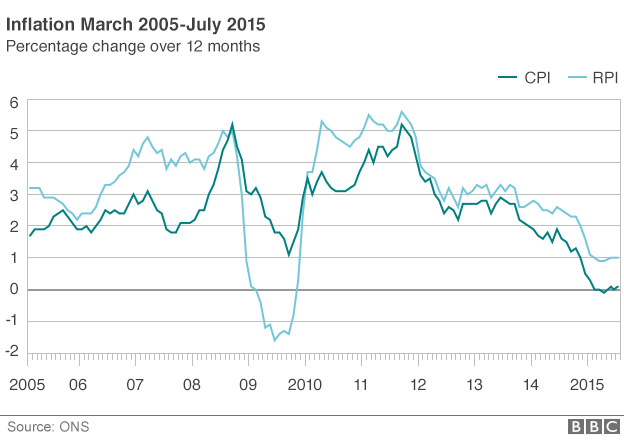

Inflation rose by just 0.1% in the last year and has been basically stagnant around zero percent for six months.

Looking at the global economy, there are plenty of reasons to think that there are disinflationary forces at work that will keep headline inflation down - the oil price is flirting with a six-and-half-year low, China's economy is slowing and food prices continue to fall.

And yet the Bank of England is increasingly signalling that interest rates will soon begin to rise, external. Given that its target is to get inflation to 2.0%, this has left many scratching their heads.

There are three reasons why raising rates may make sense, even with inflation (temporarily?) stuck around zero.

The first is that monetary policy operates with a lag. It takes something between 12 months and 24 months for the impact of a rate hike to work itself through the system and for its effects to be felt.

When setting rates at the moment, the Monetary Policy Committee isn't just looking at the current level of inflation but trying to work out where it is heading over the coming years.

With wage growth picking up and employment high, there are reasons to think that inflation should start to pick up in the months ahead.

Secondly, there's an insurance principle at work. The last recession ended in 2009 and, historically speaking, the typical UK business cycle tends to run for seven or eight years.

In other words, the law of averages suggests that we are "due" a recession at some point. It's better to go into a recession with rates standing at a level from which they can be cut.

Bigger picture

Raising interest rates now (at a gradual pace), gives room to cut them in the future if the economy needs support. And whilst it may sound perverse - "let's raise rates now so we can cut them again later" - it at least retools the policy armoury at a time when fiscal policy is still constrained by a higher level of debt to GDP.

Finally, there is the concern that interest rates that are too low for too long fuel the kind of asset bubbles that leave an economy vulnerable to shocks.

Now technically, this is beyond the remit of the Monetary Policy Committee. Financial Stability concerns are handled by the Bank's Financial Policy Committee. But such fears do play on the minds of some at the Bank.

Bank of England governor Mark Carney has to factor in the impact of a strengthening pound

But all of these arguments risk missing the bigger picture. Whilst many mortgage holders, analysts and yes, a fair few economic journalists do eagerly watch the MPC for signs that a rate rise is coming, it may already be happening.

Monetary policy in the UK may still be set to "ultra-easy", but monetary conditions are tightening.

Sterling has strengthened by around 8% in the past year against a broad basket of other currencies. That makes imports cheaper, lowering inflation, and holds back UK exports.

The interest rate - or yield - on ten year UK government debt has risen from around 1.5% in mid-January to almost 2% (although is admittedly lower than it was last year).

The impact of sterling here is important - my own sense is that if sterling hadn't risen by so much, the MPC would probably have already embarked on raising rates. In effect the markets have done some of the work for them.

Timing and pace of change

In theory moving rates from an exceptionally easy 0.5% to a slightly-less-exceptionally easy 0.75% shouldn't be a major issue for the economy.

In theory, anyway.

The process of raising rates will be fraught, raise them too slowly and inflation will rise but raise them too quickly and they risk an adverse reaction from the financial markets and a premature slowing of the real economy.

That said, for all the market obsession over the timing of the first rise (both here and in the States), more important that the start of the journey will be its pace and the eventual end point.

The Bank has been clear on this: the pace of tightening will be gradual and the eventual end point will be around 2.5% or 3.0% rather than the pre-crisis norm of 5.0%.

That does make sense, for the all the talk of the "lower bound" to interest rates (the rate below which they can't be cut) which has marked the monetary policy discussion of the past few years, rates have an effective "upper bound" as well.

That upper bound is the ability of society or economy to meet its interest payments. With household debt heading to historical highs, there is a limit to how much policy can be tightened.

Rates may start to move in the coming months, but don't expect to see 5% anytime soon.

- Published18 August 2015

- Published18 August 2015

- Published6 August 2015