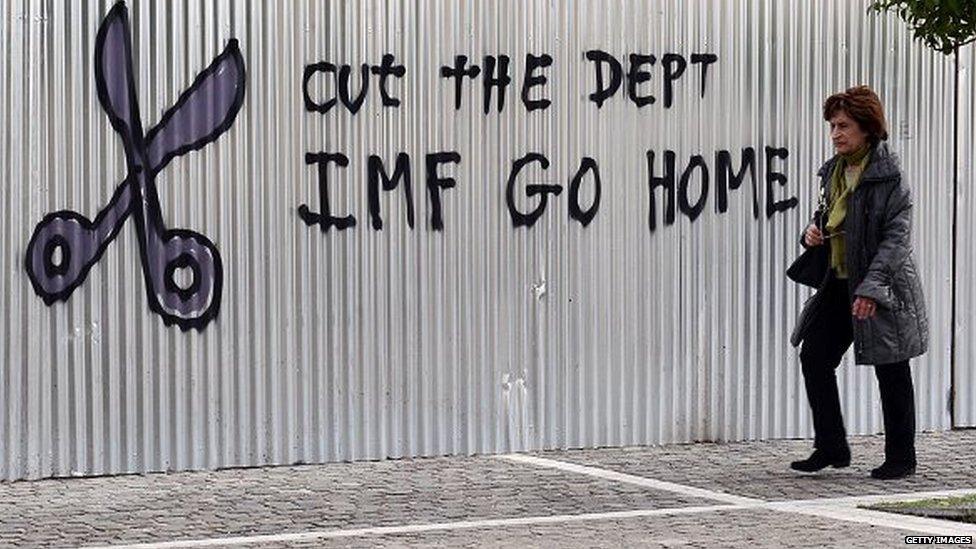

As anti-austerity protesters take to the streets in Athens, the severity of the IMF's language on Greek debt sustainability is likely to inflame demands for a Greek exit from the euro

The IMF's latest report on debt sustainability in Greece makes pretty grim reading.

It highlights a massive flaw in the deal hammered out so painfully between Greece and the rest of the eurozone - the numbers do not add up.

The IMF believes that without restructuring Greek debt, everyone is on a hiding to nothing.

Even after a third bailout, Greece would have no chance of funding itself on the open market.

Politics trumping economics

So if eurozone leaders knew that, why did they strike the deal with Greece that they did?

Germany wants the IMF involved in the Greek debt crisis because it sees the Washington-based institution as a guardian of fiscal rectitude

The IMF believes that without restructuring Greek debt, everyone is on a hiding to nothing

It comes back to a central recurring theme of the eurozone crisis: This deal was a case of politics trumping economics.

The desire to keep the eurozone together was a little bit stronger (for now) than the economic forces threatening to pull it apart.

But only just.

And once again, Germany will be the key to how this gets resolved.

The disagreement between Chancellor Angela Merkel and her Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble on how to handle Greece and its debt mountain has now come fully into the open.

Mrs Merkel agreed to a deal with Alexis Tsipras last Monday morning only after the European Council President Donald Tusk threatened to lock them up in a room.

'Deep upfront haircuts'

But Mr Schaeuble clearly wished that she had broken free.

The Greek parliament is debating a series of awkward choices over tackling the country's debt mountain

The disagreement between Chancellor Angela Merkel and her Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble on how to handle Greece's debt crisis has now come fully into the open

Many German officials, he said this week, would still prefer a Grexit.

And the severity of the IMF's language on Greek debt sustainability will only add fuel to this particular fire.

Two of the potential solutions the report puts forward are politically poisonous, and seem to have been included to create a deliberate stir. Financial shock and awe.

Direct annual transfers to the Greek budget would create the "transfer union" that so many eurozone creditor countries are determined to resist.

The idea of "deep upfront haircuts" - writing off a huge chunk of debt altogether - is equally unacceptable. And - according to Chancellor Merkel - an illegal violation of the Lisbon Treaty.

That leaves a third solution that suggests a 30-year grace period on servicing all of Greece's European debt, as well as a dramatic extension of maturities.

It would, in other words, come back into play just before 2050.

There was plenty of talk about debt restructuring during the negotiating process between Greece and the rest of the eurozone, but nothing emerged that was even close to the scale that the IMF is suggesting.

Officially there will only be a discussion of restructuring after a first review of the new bailout is successfully concluded, and that is several months down the line.

So where does that leave us?

Without being explicit, the report from the IMF implies that if nothing changes on debt, it may feel it is unable to take any part in the new bailout programme for Greece.

"We have made it very clear," says a senior IMF official, "that before we go to the board [to get any approval to take part in another bailout] we need a concrete and ambitious solution to this debt problem".

There is no doubt that the absence of the IMF would leave a large hole - both in terms of numbers and political credibility.

Germany wants the IMF involved because it sees the Washington-based institution as a guardian of fiscal rectitude.

But the IMF now seems to be telling Germany - if you want us in the game, you need to change the rules.