Yesterday marked a huge shift in government policy on wages. It is introducing a new National Living Wage for the over-25s which, by 2020, will rise to £9 an hour. This is below the level of the existing Living Wage but represents a big increase over the Minimum Wage.

In two very significant ways, the entire basis of existing policy has changed.

First, the chancellor has directly intervened in how the wage floor in Britain is set. Since the National Minimum Wage was established in 1998 its level has been set each year by the Low Pay Commission, external (the LPC), a body which brings together employers, employee representatives and independent experts.

The LPC will still have a big role to play in deciding the pace at which the new National Living Wage rises but the eventual destination has been politically set.

This has already caused some grumbling from businesses and, in the medium term, risks lowering their political buy-in to the process.

Pay/jobs trade-off

Taking direct political control of the outcome is a step in the opposite direction to those witnessed across the rest of economic policy. Monetary policy was outsourced to technocrats at the Bank of England in 1997. Yesterday, the chancellor gave more power to technocrats. In the future chancellors will always have to run surplus unless the Office for Budget Responsibility, external has decided growth is weak.

The second change is even bigger. The government's own assessment of this policy suggests that it will boost wages but also increase unemployment by 60,000 by 2020.

The previous line has always been that low pay is a problem, but it's better than no pay. However, with employment high and wage growth having lagged behind forecasts for years that attitude seems to have changed. The position now is: "Yes, there is a trade-off between pay and jobs, and we are comfortable trading marginally higher unemployment for higher earnings."

The impact of all of this on living standards for the low paid is complicated by the government's welfare cuts, especially the big hit to tax credits.

Many families, especially those with children, will lose more from the cuts in in-work benefits than they gain from increased earnings.

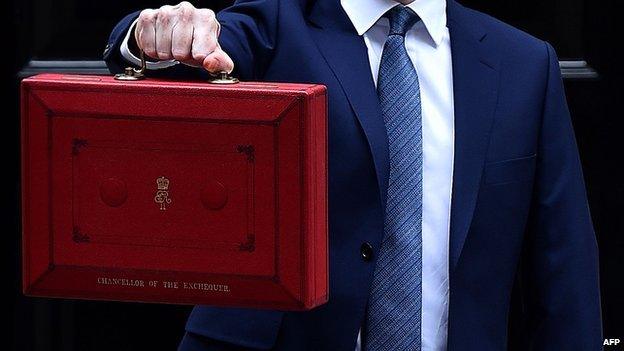

The Budget has set a challenge to employers regarding pay

The chancellor repeated an argument yesterday which has been common in parts of the British left and which has found increasing currency on the right, too: the notion that the existing tax credit system acts as a subsidy to low pay employers and has contributed to weak earnings growth.

That seems like a stretch. As employers often don't know the family circumstances of their employees, it's hard to see how they would have the knowledge required to game the system like that. Academic work has not found the oft-claimed link.

And, while the lowest paid will benefit from the new higher Living Wage, the group just above them stands to lose out: they take the benefit squeeze hit without gaining the higher wage boost.

Strategic

In some ways a grand economic experiment is about to play out, one that might provide some clues as to the real causes of Britain's "productivity puzzle": the fact that output-per-hour worked has stagnated since 2007.

One possible explanation is a compositional shift in those in work. More people are working in low skill, low wage, low productivity jobs. That's helped drive the exceptionally fast employment growth we've seen in recent years but may have contributed to dragging down average productivity and average earnings.

Employing people at the bottom of the labour market is now set to get more expensive - labour is being made less cheap.

That may discourage low skill business models by squeezing profits and it could encourage employers to get more out of existing workers either through training, investment in capital or better management.

In other words, while this policy may increase unemployment it could at the same time, potentially, increase productivity.

Was there a German theme to parts of this year's Budget?

Britain's labour market is about to become a bit less flexible. As well as costs that could bring benefits.

This was the flagship policy in a wide-ranging budget, one that shows how far George Osborne has moved since 2010. The early focus on deficit reduction is still there and the size of the state is set to shrink. But this smaller state is also taking a more direct role in macroeconomic management than was the case in the 1980s, the 1990s or even in the Blair years.

Osborne has embraced industrial activism, devolution to city regions, government-mandated wage floors and an apprenticeship policy, where firms will be charged a levy in order to avoid free riding on the training provided by others.

Cutting income tax, tightening welfare and shrinking the state are all the hallmarks of classic Thatcherism. But this is being combined with a more northern European focus on the strategic use of the state and other institutional actors to try and raise productivity and direct, to an extent, economic outcomes.

For years, the German economic model has found support on the left of British politics. The chancellor yesterday nudged Britain a bit closer towards it. Not the Social Democratic vision of Germany admired by many of those around Ed Miliband, but the Christian Democrat version currently represented by Angela Merkel.

Look at the emerging hallmarks of Osborne's chancellorship: targeting near-permanent surpluses, cutting personal taxes, trimming welfare and favouring productivity-boosting industrial policy. None of those would be out of place in a German Christian Democrat manifesto.