BBC Review

'This music tells us about Vaughan Williams' development, and that while he hadn't yet...

Andrew McGregor2002

Two CDs of Vaughan Williams? Ok, bring it on...hang on a minute: chamber music, and almost all premiere recordings. Where's this come from?

Good question. The short answer is from the period between Vaughan Williams's student days at the Royal College of Music and his studies with Ravel in Paris, thirteen years when Vaughan Williams was trying to find his voice. He and his friend Gustav Holst compared notes, and works, and probably decided that these early works were second class goods, and Vaughan Williams withdrew them all - none were published. When he died, Ursula Vaughan Williams gave them to The British Library but embargoed their performance, relenting in the 1990s - and these first recordings are made alongside the first publication of the pieces.

The C minor Quartet and D major Quintet are the earliest works -written in mid-20s - and there's nothing particularly English, or characteristic of the composer...except perhaps the Quartet's slow movement and its wistful opening line on the viola (a fleeting feeling of folksong?). But they're well-crafted, attractive, even if Brahms and Dvorak leap a little too readily into focus as models. But the C minor Piano Quintet from five years later is more self-determined and confident, a bigger-boned work that's instantly attractive. But you'd still never guess Vaughan Williams when you first heard it. With the Nocture and Scherzo for string quintet from 1906 we're closer still, and this time the folksong influence is explicit, as well as the quality of string-writing and imagination we're used to from the early symphonies.

The Suite de Ballet for flute and piano is a strange work - full of quirky, folk-tinged phrases and an almost Britten-esque piano part at times - and like everything else it's superbly played by members of the Nash Ensemble (Philippa Davies and Ian Brown)...and hey, look, there is a Pastorale, one of the two pieces for violin and piano from 1914, but it's not particularly reminiscent of the 'Pastoral' Symphony.

So why should we be interested? After all, the composer didn't want us to hear most of this music, knowing he hadn't yet found his voice. But look how enthusiastic we were about the rediscovered original London Symphony recently...this music all tells us about Vaughan Williams' development, and that while he hadn't yet found the sounds and idiosyncrasies which made him unique (and to some people uniquely annoying), he was still a damned fine composer.

These works were never going to set the world on fire when they were written. But then Vaughan Williams found the voice we know and love (or loathe), and suddenly we want to know where it came from.

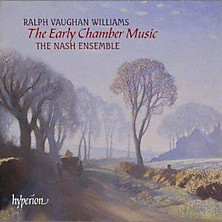

I'm sure this Hyperion set will sell very well. Maybe some of the VW-phobes should have a listen; after all it's him with most of the things they actively dislike removed. Who knows, it might even be the ideal starting point for the sceptic...