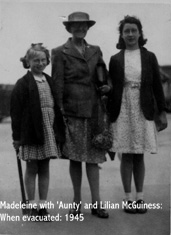

Madeleine with Miss Ratcliffe and Lilian McGuiness 1945

- Contributed by

- Madeleine Smith

- People in story:

- Edith, Grace, John, Peter, Madeleine Cardinal; Miss Eleanor Ratcliffe; Lilian and Ronald McGuiness

- Location of story:

- Oxfordshire/London/Lancashire

- Background to story:

- Civilian

- Article ID:

- A6122477

- Contributed on:

- 13 October 2005

Twice Evacuated

I was first evacuated, between the ages of 4 and 5, with my two big sisters: Edith and Grace. I was transported into a new life without any memory of a journey and without any seeming distress at leaving my parents behind. I remember very little of my life before the evacuation and while I was there I do not remember being either happy or sad, apart from on one occasion.

In the beginning the three of us lived with other children in a big home called Glebe House in Sunningwell, Oxfordshsire. I remember a room filled with beds. I remember a little copse by the house where snowdrops grew in the early spring. I remember the scent of roses in the garden in summer. There was a Shirley Temple doll, which I was allowed to play with on one occasion; she had lovely outfits to dress her in. There was a dolls house, too, and child-size pots and pans. At least, that is what I think I remember.

The house was next door to the church and I remember being scared looking over the wall at a funeral. I don’t think we were supposed to be watching. There was a duck pond opposite the house with a tiny island on it. We were warned not to go near the water in case we drowned.

I suppose I must have been contented in the home. I had my sister Edie with me, who was very good at looking after us. One day, however, a man and woman came to the home with their little boy. They were very nice and I know I liked them. They must have liked me too because they took me home with them. I believe, now, I was being placed with them as a permanent billeting but at the time I did not understand. Then it was time for me to be got ready for bed. They sat me on a table to wash me and the penny dropped: I was not going back to my ‘family’. I don’t remember feeling upset but I know I was desperate to leave. I sat looking at the door and just howled and howled. Nothing would stop me until they gave up and took me back to the home. I suppose I remember this incident so clearly because it was a traumatic one. I don’t seem to have cried when leaving my parents because I had my sisters with me, but being alone was more than I could cope with.

Later on I believe Edie went back to London. Gracie and I were billeted with a Mrs. Steptoe and her daughter, Ethel [at least I think that is what they were called]. They lived in a cottage with a walnut tree in or edging the garden. I could never make out for years why those walnuts tasted so creamy and beautiful yet shop-bought ones were dry. We went to school in the village [where it was I don’t know]. There was a sawmill with a tethered goat in the grounds next door. The school only had one big room with classes all around. I seem to have liked going to school. I believe I won a prize of a cloth doll [but perhaps I was just given it]. I remember being given a cardboard crown as well; was that for being good too? I seem to think it had that kind of good feeling attached to it.

Then we were back home in London [Beaumont Road N.19]. This was a new address for us but as I didn’t remember where we lived before going away, it made no difference. I went to Duncombe Road School and I know I loved it there. There were air raids and if we were at school we would get together in one of the big rooms and sing songs until the All Clear. But if we were on our way home when the siren went, we ran as hard as we could, hearts beating, until we got back safely. I hated being in London during the bombing. We lived in the top flat of a big house. Sometimes we would go downstairs during a raid and sit with the family who lived in the bottom flat. I hated the way everyone discussed the bombing; how they would say, “Be quiet!” when a ‘plane came over so they could work out whether it was “one of ours”. I would stuff my fingers in my ears so hard I made them sore, so that I could not hear the bombs coming. I hated the tension, and even the relief when nothing bad happened to us. It was dreadful at night after a raid, when we could hear the dig, dig, digging of helpers, searching for survivors in the rubble of bombed houses. Sometimes, the next day, we would see people being carried out, wrapped in blankets. It preyed on my mind so much that I was a bundle of nerves and I was glad when at about the age of 8 we were evacuated again. Before that, we were given a place in an air raid shelter in our road. One day I ran fast out of the house towards the shelter and fell on the curb. I had an enormous bruise on my hip and my mother said they would probably not let me be evacuated because of it. It was a great worry, but of course they did!

My second evacuation was to the village of Penwortham, near Preston, Lancashire. This time I do remember the journey, in a train, and I remember being fed up because my mother had given me cheese sandwiches and I hated cheese.

On arrival, we stayed overnight in a big hall in Preston; then we went on to Penwortham, to the village hall. I cannot remember how many of my siblings came with me on this occasion. I know Edie was not with us but Grace was, together with my brother John. Perhaps my brother Peter was with us too but, in the event, we were all separately billeted and saw little or nothing of each other during our stay. I do feel bad about not remembering my family but I do think that a great deal of this was due to the traumatic times in which we lived. Being evacuated twice at an early age could not have helped my brain to make connections. I was here, there and everywhere and seem to have lost the power of feeling fondness for or closeness to anyone. I blame it on the war but, of course, it may be a personality trait!

I was taken in by a Miss Ratcliffe, who lived opposite the church hall. She already had two other evacuees, a brother and sister from Manchester. Lilian and Ronnie were older than I was and were well established in the household. Their mother had died but they had good contacts with their other relations. They were [or seemed] very confident, big children; more like grown-ups. They teased me from time to time but I know they also looked after me. I was such a nervous child: scared of the dark and hating the things they loved, like mixing with people and children’s parties. Again, that might be a personality trait because I am like that still!

Being in Lancashsire was an education in itself. Auntie, as I called Miss Ratcliffe was a stickler for good manners and clean habits but she was kind; she was very kind. I was, though, a little afraid of her because I was often doing the wrong thing. She taught me so many things that helped me in later life and I will always be grateful to her. I learnt how to darn and mend my own clothes. One thing she insisted on was my writing to Mum and Dad every week. This was to prove a great help in keeping me at least slightly ‘attached’ to my parents. It was also a wonderful way of learning to write and spell and learn the rules of letter writing. My father wrote back and would regularly send me two sixpences placed in slotted cardboard, which Auntie made me save. I didn’t like saving but how I loved it when she allowed me to spend some of it on a special occasion! Auntie also introduced me to the public library and, from then on I invariably had my head stuck in a book. From the library I would take quite young stories to read but, in between, I was reading all of Auntie’s own books: A Basket of Flowers, The Old Curiosity Shop, and Pilgrim’s Progress among them. I have belonged to the Public Library ever since.

I was a plain child with one crossed eye [my family said I got it from screaming so much] but I felt like a princess in some of the clothes I wore at this time. I was given some of Lillian’s cast-offs and I particularly remember a yellow and white checked dress with a lovely swirly skirt. I wore a straw hat to church on Sundays and little white gloves. We always dressed in our best, too, when we went to town [Preston]. Lilian would sometimes take me, without Auntie in charge, and we would have tea in a proper tearoom with white tablecloths.

We had clothes from the parcels sent from America and I remember being absolutely delighted with a warm coat, which was patterned in big black and white checks. There were new shoes from America too.

I had so many good experiences in Lancashsire that I would never have had if I had stayed in London. We went to the seaside, to St. Anne’s, and rode on donkeys and had ice cream! I dug in the sand for the first time in my life. We went on picnics to a place called Little Blackpool, which was really a sandy riverbed, I think. There was a pear tree in the garden of our house and raspberries for tea in its shade in the summer.

I went to Cop Lane School and the walk every day was a wonderful experience past the hedges that contained the fields. We ate ‘bread and cheese’ [new hawthorn leaves] as we went or sucked the honey from white dead nettles. In the winter the hedges were rimed with frost and so were the spider webs, which, on summer mornings, dripped with dew. At school I received my first and only corporal punishment: I was whacked with a ruler for not being able to do my sums. Oh how it stung! And I was backward at Arithmetic all my school days, not understanding anything much until I went out to work.

At Easter we rolled decorated eggs down a hill until they broke. I was given presents from Auntie to mark the season. I think I had sewing cards, which I loved. It was even better at Christmas time. There was a fold-out tree with real little candles on it and other pretty decorations. I had lovely, thoughtful presents then, and for my birthday: a New Testament, my very own prayer and hymn book [I loved church at that time], a rag doll and a brooch that spelt my name — with a little red jewel on the end. I lost the brooch because I was, and still am, a very careless person. I grieve it still.

I made friends with two sisters who lived at the vicarage and I played for hours in the vicarage grounds. There was a big old beech tree that swept one of its branches nearly to the ground, which we would ride on as our horse. There were shrubs set out at one end of the lawn, which made a wonderful stage with entrances and exits. We played at being vicars and congregation in the big old coach house [?], making an altar and getting flowers for it.

On VE day we had a big bonfire for the neighbourhood and we roasted potatoes in the ashes. We had some chocolate to eat too.

When it was time to return to London I was ill and had to stay behind. But, eventually, I too, made my way ‘home’.

I cannot remember how I felt at the time; I probably didn’t feel anything [as was my wont]. Despite all the wonderful experiences and loving care I had been given, I had not made an emotional bond with Auntie and the others. I didn’t seem able to do that. And when I got back I did not feel connected with my family either. It makes me weep now to say this. Those connections were never fully made — and I am 71 years old now. I always felt an outsider in the family. At the time I thought it was because the others did not like me; they looked on me as different, even my Mother. But now I know it was not a one-sided situation. I know now that I was a snob because I had learnt ‘better’ ways and had, definitely, lived in a better style in Lancashire. Eventually, my mother had 11 children altogether. There was never time for anything but babies in her life. I do not blame her now but I believe I blamed her then. And we were poor. However, I did have a good relationship with my Father. Like me, he was interested in reading; he loved poetry as I did; he was a gifted artist and also crafted wonderful things out of practically nothing, like aeroplanes and calendars, hand-made cards and silk flowers. We had a rapport that I scarcely recognised until after he died. I also did, finally, make connections with my siblings, especially those younger than me. I tried to take an interest in them as people had taken an interest in me. But, being me, the bonds are very loose. My parents are dead now and most of the rest of the family keep in regular contact with each other. I am still on the edge; and I find I cannot be anything else. I love them in my own way, but at a distance. My own dear family: my husband, four children and two grandchildren I love absolutely; that is where my feelings lie.

When I think of the past, I wonder whether my experiences made me what I am, or whether I am how I would have been had I not been evacuated. Would I have been closer to my parents and siblings if the war had not parted us? Would I have learned to love books in the same way? Would I appreciate nature as I do now? Would I have met and married my husband who worked in education most of his life, as a teacher of English, then Drama and finally as head teacher of a primary school. Would I, myself, have ‘gone in’ for further education as an adult, as I did? I do not know. But I am still learning: about the world and about myself.

Madeleine Smith, née Cardinal

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.