- Contributed by

- DPITNEY

- People in story:

- Walter Douglas Thain

- Location of story:

- Royal Naval Career - Aircraft Carriers

- Background to story:

- Royal Navy

- Article ID:

- A3800206

- Contributed on:

- 17 March 2005

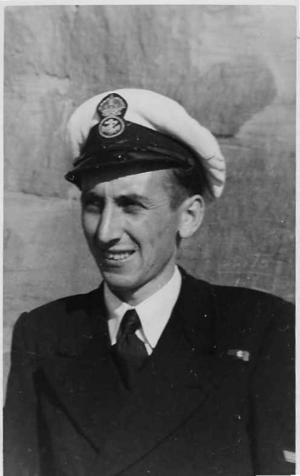

Walter Thain in the uniform of the Royal Navy taken about 1940

These recollections were written by my father in law Walter Douglas Thain in the late 1990’s. In transcribing them I have kept them as near to the originals as possible.

It must be one of the peculiarities of life that we seem to reminisce, as we get older. All I know is that the Royal Navy was rarely if ever in my thoughts during my life but now I find myself looking back and doing just that.

After 50 years there are obviously many things I do not recall the ones I talk about here are all ‘instant recall’ memories.

By way of preface let me tell you that in 1939 age 20 I was very confident, having been to Chivers School, posh name ‘Esplanade House School, Southsea’. I later heard the saying ‘there is hardly a wardroom in the navy that hasn’t got as ex-Chivers boy in it’.

When I was younger I was very keen to join the Navy as an engine room artificer — it was the ‘in’ thing to aim for. After that phase I fancied flying — still in its infancy 50 years ago. I applied to join the RAFVR as an observer — now called a navigator. I got accepted on my school qualifications as I had passed the RAF apprentices examination. I went to Southampton and passed the stiff medical including blowing up the mercury to a certain degree. I had heard nothing by the time war started so I joined the navy instead thinking I would switch later.

SEPTEMBER 1939 - JOINING THE ROYAL NAVY

I joined the Navy the first month of the war in September 1939, RNVR actually. My Navy number was PDX264 (FAA) RNVR. I spent one morning in RN Barracks at Portsmouth. I had to see a Naval commander. I told him I worked in a large store and he promptly said, “supply branch”. I kept quiet that I had already applied to join the RAF as an observer. I was sent to Scapa Flow in the Orkneys to join the Ark Royal for training. It was not very organised at that stage of the war. After about five days in training and an uncomfortable journey I finished up on the depot ship Iron Duke an old WW1 battleship. Had to cross the Pentland Firth in a little ferry from Scrabtser near John O’Groats, it was rough and cold and I felt seasick. After two days on the Iron Duke waiting for transfer to the Ark Royal a German submarine got through the boon and sunk one of our battleships the Royal Oak. I just missed the ‘Ark Royal’ and came back to RN barracks at Portsmouth with the survivors from the ‘Royal Oak’. I heard lots of horrible stories from them so I wasn’t slow on realising the horrors of war.

I was then sent to join the ‘Ark Royal’ somewhere on the way to the South Atlantic to search for the German’s new fast battleship the Graf Spey.

I had to go to Liverpool to join a small liner 11400 tons, an elder ‘Dempster’ line AB0550. There were only about twenty Naval men on board. The rest f the passengers were the colonials going back to Africa after a vacation in the UK. I had a shared cabin and lived like the paying passengers. I thought ‘this is the life’, that feeling wasn’t to last long. I did get some work to do, the twenty odd of us (RN) had to do watches on the bridge including nights. I soon found out about the middle watch i.e. 12 to 4am. The captain, merchant nay of course, was a bluff genial typical old school type, friendly. I had a pair of binoculars and was told to look out for U boats — German submarines. If the captain knew that I’d been selling mans wear the previous month in the Co Op he might not have been so happy!

I was terribly seasick until I got used to it. The ship used to roll and creak and groan. Going up to the bridge in a howling gale at midnight was quite a new experience. The noise of the wind through the rigging was tremendous. Also, I had all the jabs in the book, as they hadn’t been given before I left the UK. Yellow fever was the worst. The effects of these plus the seasickness and I felt rotten. We arrived in Freetown — Sierra Leone — known in those days as ‘white men’s grave’ to be proved true shortly. It was light at six pm and jet back at six fifteen pm. Very hot and humid.

I found the ‘Ark Royal’ there attached to 820 squadron then with Swordfish aircraft — Stringfellows. I relieved a regular serviceman, name of Rapson, going home. It was just a case of hello and goodbye. I was then put in charge of all the squadron stores, remember, I had had no training whatsoever. Normally, you would do a period of ‘square bashing’ then various courses including air stores, Naval stores and victualling. I had a nice office attached to the stores, very lucky. I soon realised that the supply branch of the Royal Navy had many privileges denied to other branches. Silly, but a throwback to the days of Nelson, the pen is mightier than the sword etc. Few could write then, so writers were looked on as better, different, clever or what have you. This led to grumbles, quite understandably from the mechanics, quite a lot were RAF in those days and most eventually transferred to the Navy.

This led me to be put in e ‘store ship’ gang. I was in the bowels of the ship stripped to my shorts stowing heavy sacks of flour being lowered down the hatch this was in harbour and terribly hot and claustrophobic. Heaven knows what the temperature was. I soon forgot the pleasant trip out I’d had. Eventually, a supply Petty Officer saw me and said ‘supply ratings don’t do store ship duties, they are in charge of them, leave at once’. So feeling pleased, hot and tiers I staggered off for a shower and grateful for being in a privileged branch When I got to know the mechanics better I made up for it by coaching them with algebra, trigonometry, Euclid etc. They were swotting for their exams, which were taken on board as time etc. allowed. There were aircraft fitters, riggers, electricians, armourers, radio etc. later we had radar mechanics but radar was not around then only in primitive form, great strides were rapidly mad with this after a while. We had a homing beacon on the mast and I know how that worked.

Whilst at Freetown, huge Malaria tablets were issued before going ashore. In my ignorance I did the same as most of the men and slung them quietly over the side of the ship. Freetown was very colourful. Banana’s were1s a stalk containing about 50 or more. Found out what a ‘John Collins’ was. Lots of canoes full of jet-black locals buzzing round the ship. We were told later that one of them was clever enough to be a spy and was sending radio information of news of the Ark Royal and when she sailed to the Graf Spey or Germany. We used to swap trinkets with the locals over the side of the ship.

Our squadron writer, name of Wright, was taken ill and died on a hospital ship four days later of T.B., called galloping TB in those days.

We sailed out into the South Atlantic searching for the Graf Spey. We did thousands of miles, crossing the Equator several times. In peacetime they would have had the usual Naval ceremonies and skylarks but all I got was a crossing the line certificate, which I still, have as I took it home on my first shore leave later. I saw sperm whales, lots of dolphins, flying fish, a waterspout and other creatures of the sea. An albatross followed us for weeks, wingspan 12 to 15 feet. I still have a picture of it. There were huge sea swells of 20 to 30 or more feet. It would look calm, but if we had to lower a ships boat to pick up anyone in the sea I realised how powerful the sea was, one minute the boat would be in a trough, the next minute it would be almost level with the lower deck. Later on in the war and nearer home waters where the German submarines were, we never stopped of course, but not so many U boats were being reported so far south at that early stage of the war.

Dawn action stations every morning, about five am I think it was. So we were all rather tired all day, not conducive to top efficiency but that’s how it was. There was no radar to my knowledge so we didn’t know what was going to be near us at daybreak. We had the usual ‘gung ho’ captain — name of Powell — later an Admiral — came up through the ranks that was fairly unusual then. He was a nice chap but like most regulars, saw the war as their chance for glory and quick promotion which they got of course, One pitch black night we chased what he thought was the ‘Graf Spey’, caught it, and it was a P and O liner going flat out and all blacked out. It had colonials and others aboard heading for Capetown. It was before all non-Navy sailings were stopped for the duration of the war. We had 4.5 guns to the Graf Spey’s 15” so it’s just as well it wasn’t her or I wouldn’t be writing this. We captured a German armed merchantman cruiser ‘Uhenfells’ and we put marines on board and sailed it to port. We stopped another large armed German liner ‘Watussi’ which we scuttled. Some of the crew on board were looking thoroughly dejected. It was a sad and impressive sight as she went down.

There was a tremendous amount of flying going on searching for the ‘Graf Spey’. Air crews got very tired also the aircraft had to be kept serviceable as best as possible, lots of work for me. I managed to wangle three trips up on anti-submarine patrols in place of the observer/navigator. They were given a rest if possible, as the weather was very good and clear. I flew with Lt R.R. Everitt and Sub Lt Boulding.

I was the only one daft enough to ask for trips up. I was friendly with most of the aircrews s I used to have dealings with them in my store duties. I was nicknamed ‘the flying store basher’. I went off the catapult once, so at least I can say that I’ve flown on operational flights although in wartime all flights were basically operational, but most not over the Atlantic or from carriers. I took a few pictures whilst up which I still have. I also still have the camera a 620 Kodak (620 films) bought in Gibraltar, should have bought a Leica or Zeiss as comparatively cheap but I didn’t have much money of course. Graf Spey was reported near the west off Rio de Janeiro. We had to call into Rio to re-fuel along with the ‘Renown’. We sailed into Rio harbour at dawn on a beautiful day. It is reputed to be the most beautiful sight in the world and it looked it. No one was allowed ashore of course, as Brazil was neutral and in any case I guess we would have lost half the crew. All the matelots could do was look at all the sunburnt girls in their bikini’s, that’s as far as they got.

Everyone was expecting a battle with the German battleship but as everyone knows she scuttled in Montevideo harbour after being engaged by three very small cruisers, which had arrived, ‘Ajax’, ‘Exeter’ and ‘Achilles’. We escorted them back to Freetown. They were badly damaged and they got a huge welcome when they arrived back in the UK.

Continued in Part 2

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.