If you are researching ancestors from Africa or the Caribbean there are some specialised routes to the past that you might like to follow .

By Kathy Chater

Last updated 2011-04-27

If you are researching ancestors from Africa or the Caribbean there are some specialised routes to the past that you might like to follow .

Researching your family history if you're of African Caribbean descent presents some interesting challenges - and there are many resources that can help you.

From very early in our history, there were people of African descent in Britain. Some arrived as part of the Roman army after 55 BC. Others came at the time of the Tudor kings and queens in the 16th century.

The most recent wave of immigrants started to arrive in Britain a few years after World War Two.

Later they came through trading links with Africa, America and the Caribbean Islands - often, especially in the 18th century, as slaves, but also as seamen, students and missionaries. The most recent wave of immigrants started to arrive in Britain a few years after World War Two - in response to the British government's plea to its colonies to send workers to help with post-war reconstruction.

It is with these starting-off points in mind that you will probably want to begin your research. First read Wayne Younge's story to get a flavour of where your quest might take you - then follow on for more about the history of British people of African descent, and information to help you look for the records that relate to your own family members.

You should be able to find out a lot via the internet links given in 'Find out more' at the end of this article, and some of the British sources listed, before you need to approach Caribbean record offices.

Government building, Bridgetown © "Growing up in England, there was always the knowledge that I'm descended from slaves. That alone was an exciting thing for an impressionable teenager to think about, but my interest in genealogy didn't start until my mother died. Then I realised that there was a lot about my mother's life before I was born that I had no idea about. Like most people, I knew a little about my grandparents - but before that my knowledge petered out.

Government building, Bridgetown © "Growing up in England, there was always the knowledge that I'm descended from slaves. That alone was an exciting thing for an impressionable teenager to think about, but my interest in genealogy didn't start until my mother died. Then I realised that there was a lot about my mother's life before I was born that I had no idea about. Like most people, I knew a little about my grandparents - but before that my knowledge petered out.

There was something truly wonderful about leafing through records written over 100 years before.

"A trip to Barbados in 1997 was to provide some of the answers I was looking for. But first, I spent many happy hours trawling the internet for information, and I used my new knowledge to quiz family members about our family history. I used newsgroups to post enquiries for specific people, and a package called 'Brother's Keeper' to chart my findings.

"I also quizzed my grandmother to get as much information as I could. I came away with a group of names and possible birth dates, and armed with all this information I arrived well prepared at the Department of Archives office, St Michael, near Bridgetown.

"There was something truly wonderful about leafing through records written over 100 years before, although I found a few problems. In Barbados in the 19th century a person was not routinely known by their first name. Parents were often either not married or were married only after the birth of a child.

"Generally, my ancestors were labourers or agricultural workers - though according to Gran we are also descended from a Caribbean pirate called Sam Hall. (I haven't been able to prove this yet.) It took me a couple of days of time-consuming and patient checking of the records to get one line of my family going back to 1832, and many others to the back end of the 19th century.

"Recently, after my grandfather died, my uncle mailed to say he'd found that one of my ancestors was the son of the Attorney General and Chief Justice of Barbados. This was exciting news - there's data going back from him to the early 1700s. This is another link I'm still trying to prove."

In 1492, the explorer Christopher Columbus crossed uncharted seas on a voyage of discovery on behalf of the Spanish king Ferdinand II. He arrived on a Caribbean island that he named San Salvador, in the Bahamas, and laid claim to it for Spain.

In the wake of this discovery, other expeditions across the same seas were organised, from Portugal, France, Britain, the Netherlands and Denmark - all countries eager to colonise lands hitherto unheard of in Europe. These European powers eventually took over all the Caribbean islands, as well as mainland America to the north and south.

The European powers during this period were almost permanently at war with each other ...

At first the colonisers tried to use the labour of the indigenous population, and people brought from their own countries, to develop the land. But when this failed they brought in slaves from Africa.

The slave trade developed from around 1700, and was not abolished by Britain until 1807 (by other countries not until many years after that). During that time many slaves arrived in Britain itself, mainly as servants and seamen.

Some arrived directly from Africa, others as the servants of visiting plantation owners from America - a British colony until 1777 - and the Caribbean. Although most will have returned with their masters from whence they came, thousands stayed in Britain, married British people and settled down here.

During the 19th century, with slavery abolished, fewer people of African or African-Caribbean descent arrived in Britain, but there was still a steady stream of seamen, students and missionaries. Again, some were here for only a brief period, while others remained for good.

As slavery disappeared, and new systems for working the plantations evolved, the Caribbean islands developed in a range of ways. The differences grew out of the varying cultures of the European powers controlling the islands, and the different crops that individual areas were best suited to producing.

The European powers during this period were almost permanently at war with each other, and the territories of the Caribbean were often involved in these conflicts, sometimes changing hands as a result. Grenada, Dominica and St Vincent, for example, were under French rule until 1763, when Britain acquired them. Trinidad was Spanish until 1802, but neighbouring Tobago changed hands among the Dutch, British and French until 1814, when it was ceded to Britain.

As well as the changing relationships between the peoples of the different islands, there was always a great deal of trade between North America and the Caribbean. Some families owned property in both places, with slaves moving between them.

The 'Empire Windrush', which brought the first post-WW2 Caribbean immigrants to Britain © The brief details given above all affect where records for different periods will be found, so you will need to bear them in mind as you start looking for records relating to your own ancestors.

The 'Empire Windrush', which brought the first post-WW2 Caribbean immigrants to Britain © The brief details given above all affect where records for different periods will be found, so you will need to bear them in mind as you start looking for records relating to your own ancestors.

Before you even start, though, get as much information as you can from members of your family. Find out where your ancestors lived, what their jobs were and for whom they worked.

Remember that not everyone worked on plantations as field workers or domestic servants.

Remember that not everyone worked on plantations as field workers or domestic servants. Many 18th- 19th- and 20th-century Afro-Caribbeans had a skilled trade and lived in towns. Others were fishermen, dockers or seafarers. This will all give you ideas about where to look for records that relate to your family.

In the 20th century, people from the Caribbean served in both world wars, and many of their records can be found through military sources. For details of some of these sources visit the military research timeline. This might be the place for you to start, if you know one of your relatives served in one of the armed forces.

Part of the passenger list from the 1948 voyage of the 'Empire Windrush' © Most of those who settled in Britain in the later 20th century came after 1948, when the Empire Windrush, and other ships, brought people from the West Indies to help with the post-war reconstruction of the UK. Ships’ incoming passenger lists up to 1960 are available online at ancestry.com, with the originals at The National Archives. Those who came by plane or who came only from ports within Europe are not usually recorded.

Part of the passenger list from the 1948 voyage of the 'Empire Windrush' © Most of those who settled in Britain in the later 20th century came after 1948, when the Empire Windrush, and other ships, brought people from the West Indies to help with the post-war reconstruction of the UK. Ships’ incoming passenger lists up to 1960 are available online at ancestry.com, with the originals at The National Archives. Those who came by plane or who came only from ports within Europe are not usually recorded.

You will also find records relating to Afro-Caribbean immigrants, from the point of their arrival in Britain, in UK genealogical sources. Their births, marriages and deaths will have been recorded along with the rest of the population, and all kinds of other standard documents will have been produced.

For information about Caribbean families before this time, you may need to look at family records in Caribbean record offices - in particular records of birth or baptism, marriage, and death or burial - although they have by no means all survived. In the early 1980s, for example, there was a fire in the court house of St Kitts, which destroyed many records. Hurricanes have also taken their toll, as in Montserrat. If you are unable to visit the Caribbean yourself, it may be possible to hire a local researcher, but before you do either of these it is definitely worth checking which records are already available in the UK.

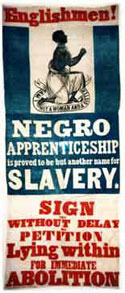

Slavery (as opposed to the trade in slaves) was abolished in the British West Indies in 1834, largely thanks to public opinion in Britain © Another source you might think about is estate papers. These document the ownership of colonial plantations, and may well contain leads for the family historian.

Slavery (as opposed to the trade in slaves) was abolished in the British West Indies in 1834, largely thanks to public opinion in Britain © Another source you might think about is estate papers. These document the ownership of colonial plantations, and may well contain leads for the family historian.

Most are private papers belonging to the families who owned the estates, and may have been brought to Britain, although some have been deposited in records offices on the islands. If the papers did come to Britain with the family, they may now be in a county record office or other institutional library.

Before slavery ended, the authorities in the Caribbean places ruled by Britain had to send back information to the British government. As the government was mainly interested in collecting taxes and other financial matters, most of these records relate to the estate owners, but there are some containing lists of slaves. These government-related papers are now held in The National Archives, although in some cases there are copies in the record offices of former Caribbean colonies.

For further sources of information read history books about the place your family came from. Check the books' footnotes and bibliographies for details of local records or estate papers - and where they are currently located.

Good luck with your researches!

Books

Immigrants and Aliens by Roger Kershaw and Mark Pearsall (The National Archives, 2000)

Tracing Your West Indian Ancestors by Guy Grannum (The National Archives, 2002)

Migration Records by Roger Kershaw (The National Archives, 2009)

Moving Here: a database of digitised photographs, maps, objects, documents and audio items recording migration experiences of the past 200 years.

The Caribbean Gen Web Project a comprehensive list of records with links to sites with more information.

Society of Genealogists: Library has a good section on the West Indies, containing books about the different islands (including some of the non-British ones like Puerto Rico), and transcripts of parish registers. It also has 'Caribbeana', a series of publications containing transcripts of all kinds of records relating to the British West Indies.

The National Archives: a vast repository of documents and information, it also provides detailed research guides and much more.

Latter Day Saints Family History Centres: an international organisation, which has copied many genealogy records from around the world for researchers to view on microfilm. You can order material to your nearest Family History Centre.

Who Do You Think You Are? magazine: a ‘getting started’ guide about Jamaican Family History.

Kathy Chater is a lecturer on family history, and a writer on the topic for, among others, History Today . She has a particular interest in black people's history. Books she has written include Family History Made Easy (Southwater, 2004), and Tracing Your Family Tree (Lorenz, 2003).

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.