As Shakespeare's fame grew, references to him began to appear in some enlightening documents. They give an intriguing account of high and low living, tax dodges, and the steady acquisition of property.

By Michael Wood

Last updated 2011-02-17

As Shakespeare's fame grew, references to him began to appear in some enlightening documents. They give an intriguing account of high and low living, tax dodges, and the steady acquisition of property.

The scarcity of real knowledge about William Shakespeare, especially his early years, has led to theories that he didn't exist as an individual at all, but was really another writer working under a pseudonym. Most serious historians however, regard these theories as baseless: the later years of Shakespeare's life are in fact relatively well documented, for someone of his standing.

...his early experience of belonging to a persecuted minority could have played its part in ...a self-effacing stance.

In addition, the playwright's colleagues, in their commemoration volume of his plays after his death (the First Folio, published in 1623), confirm that William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon was the author of those plays. Evidence that a poet of this name, from Stratford, did exist is also backed up by further documents from around the same time, including Shakespeare's will (now in the National Archive, at Kew), and his funeral monument (in the church at Stratford). A look at the main documents relating to his later life, and some recent finds, may offer further clues.

Shakespeare's formative years had been spent at a time poised between two worlds - the old world of Catholicism and the new world of Protestantism. Then, in the aftermath of Spain's failed attempt, in 1588, to impose Catholicism on the English, the new Protestant establishment had triumphed. Thus, by the turn of the century, Catholicism had become a minority religion.

Stained glass in the church at Wroxall. Shakespeare's grandfather Richard was bailiff here and Shakepeare women were prioresses at the nunnery © It seems likely that in the privacy of the Shakespeare family home the old faith may have been foremost. His grandfather had left a will demonstrating strong Catholic beliefs, and his father appears on a list of Catholic recusants in 1592. Perhaps his early experience of belonging to a persecuted minority could have played its part in what appears to be a self-effacing, even evasive, stance as a writer in his later career in London.

Stained glass in the church at Wroxall. Shakespeare's grandfather Richard was bailiff here and Shakepeare women were prioresses at the nunnery © It seems likely that in the privacy of the Shakespeare family home the old faith may have been foremost. His grandfather had left a will demonstrating strong Catholic beliefs, and his father appears on a list of Catholic recusants in 1592. Perhaps his early experience of belonging to a persecuted minority could have played its part in what appears to be a self-effacing, even evasive, stance as a writer in his later career in London.

It is intriguing, for example, that he was never picked up on church attendance lists, including during his years of lodging within the London estate known as the Liberty of the Clink, in Southwark, belonging the Bishops of Winchester. He is known to have lived here in 1599, and maybe later.

It is perhaps also significant that his one known house purchase in London (for which the mortgage documents survive), was made in 1613, after he had retired to Stratford - and that this house had once been well known to the government as a Catholic safe house.

In his private life Shakespeare is always hard to pin down, but interesting light can be cast on his time in London by looking at the neighbourhoods he is known to have frequented. London has a very rich body of source material, much of it accessible in the Guildhall Library, including parish registers, guild companies' accounts and memoranda books.

Early books on London include the indispensable guide book of John Stow from 1598, and the Carriers Cosmographie by John Taylor (on the London inns). Among court records, the Middlesex Court Sessions offer vivid detail on crime in Shakespeare's Shoreditch.

...it is possible to paint a vivid picture of the places where Shakespeare worked...

The National Monument Record has wonderful black-and-white photographs of areas such as Bishopsgate, which were not destroyed until the 19th century, so record the city as it had been in previous centuries. Out of all these records it is possible to paint a vivid picture of the places where Shakespeare worked, and to begin to map the pattern of his friends and contacts.

Eight addresses are suggested by this range of sources, and include the rough theatre area of Shoreditch, where tradition says Shakespeare got his first job as a theatre runner, prompt boy and horse holder.

Nick Bottom, a character from 'Midsummer Night's Dream' is turned into a donkey © His early fame came through history plays, and by 1594-5 he was writing his first masterpieces - Midsummer Night's Dream and Romeo and Juliet. His first definite address is in Bishopsgate, which he left as a tax debtor in autumn 1596, soon after the death of his son. He is thought to have lived there from 1592, maybe earlier. He may have moved from Shoreditch to the better neighbourhood of Bishopsgate once he had started earning good money.

Nick Bottom, a character from 'Midsummer Night's Dream' is turned into a donkey © His early fame came through history plays, and by 1594-5 he was writing his first masterpieces - Midsummer Night's Dream and Romeo and Juliet. His first definite address is in Bishopsgate, which he left as a tax debtor in autumn 1596, soon after the death of his son. He is thought to have lived there from 1592, maybe earlier. He may have moved from Shoreditch to the better neighbourhood of Bishopsgate once he had started earning good money.

His next address was in Paris Garden, on the south bank of the Thames, near the new Swan theatre. Here it is that his company, who were in dispute with their landlord in Shoreditch, are thought to have played the winter season of 1596.

Southwark was an edgy and violent area with 300 inns and brothels, bear and bull baiting, gambling dens and skittle alleys. The tax men tracked Shakespeare here, in 1596-7, and he is also named in connection with a GBH summons in the area, with Francis Langley, the owner of the Swan.

Local landmarks again appear in the plays of this time - the Castle inn (today's Anchor, in Bank End), and the Windmill, are both named in the Henry IV plays. Also, famously, the Elephant, at the end of Horseshoe Lane, is named in Twelfth Night as the 'best place to Lodge'.

By spring 1599, when the Globe theatre in Southwark was under construction, William was living in a house on the site; around this time he is also recorded as living in the Liberty of the Clink, close to the Bishop of Winchester's palace, whose ruins still survive today near Borough Market.

By late in Elizabeth's reign, Shakespeare was a famous poet and playwright, and there are a number of references to him and his plays between 1598 and 1602. The contemporary critic Francis Meres refers to him as the best English writer for comedy and tragedy.

His life in Silver Street is lit up by a vivid series of documents, and in the court case he is named 26 times...

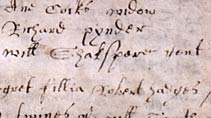

In early 1602 Shakespeare was living back north of the river. A court case over a disputed dowry shows he lodged with a family named Mountjoy, in a house on the corner of Silver St, and that he was the go-between in the marriage of Marie, a daughter of the family, to their apprentice Stephen Belott. This took place in November 1604, and the playwright may still have been living there through the writing of King Lear (autumn-winter 1605-6?) and Macbeth, which was written through summer 1606, and performed late that year.

His life in Silver Street is lit up by a vivid series of documents, and in the court case he is named 26 times, signing one deposition in his own hand. When questioned, he told the court of Mountjoy's 'goodwill and affection' towards the apprentice, and how Marie's mother 'did solicit and entreat [me] to move and persuade Belott to effect the marriage': Shakespeare for once speaking in his own voice!

Illustration showing a reconstruction of New Place, which Shakespeare bought in early 1597. It was the second biggest house in Stratford © It has always been assumed that throughout these years Shakespeare's family were living back in Stratford. (He would have gone home for a lengthy period only at Lent, when the theatres were closed.) The death of his son Hamnet in the summer of 1596 must have been a devastating blow, and may shadow some of the sonnets written the next year. Certainly, some of the things the playwright did in the aftermath are revealing.

Illustration showing a reconstruction of New Place, which Shakespeare bought in early 1597. It was the second biggest house in Stratford © It has always been assumed that throughout these years Shakespeare's family were living back in Stratford. (He would have gone home for a lengthy period only at Lent, when the theatres were closed.) The death of his son Hamnet in the summer of 1596 must have been a devastating blow, and may shadow some of the sonnets written the next year. Certainly, some of the things the playwright did in the aftermath are revealing.

...and a note of William's remark that his great grandfather had fought valiantly for Henry VII.

Ten week after the death of his son, William applied for a coat of arms, at the College of Arms. The College still preserves the documents, and a note of William's remark that his great grandfather had fought valiantly for Henry VII.

Then, early in 1597, Shakespeare bought New Place, the second biggest house in Stratford. The only surviving letter to Shakespeare, from his friend Richard Quiney, dates from this time, and contains a request to borrow money. It seems likely that William, like his father, operated on the side as a moneylender.

There are other fascinating documents naming Shakespeare, at the National Archive at Kew. Among the papers is the royal license granted to William and his company to do shows all over England, under the name of the King's Men. Also at Kew is a document of the Master of Revels, long thought a forgery but now proved authentic, which lists the entertainments put on at King James's first Christmas court, including plays by 'Shaxberd'.

Yet another document lists the issue of 'scarlet red cloth' to William and colleagues for the 'royal entry' of 1604, when James showed himself to his subjects in an ostentatious procession through London. The cloth was for William's scarlet woollen livery, which he wore on that day as a gentleman usher, and is shown perhaps in the famous Folio engraving of him.

The question of Shakespeare's religion is an interesting one. We can tell from his works that his knowledge of the old Catholic rituals never left him. As a young man, he may have moved between both worlds, like many of his generation. But in his case, the persistence of private loyalties may have been more a matter of choice.

...a story surfaced in the Cotswolds that Shakespeare had "dyed a papiste"...

A sensational new analysis reinforces this idea. It concerns Shakespeare's most enigmatic poem, The Phoenix and Turtle, published in 1601. Until now, this work has defied all attempts at explanation, but it has recently been convincingly argued that it was a memorial poem for Anne Line, a Catholic widow executed at Tyburn in 1601 (see Times Literary Supplement, April 2003).

If this account becomes accepted, it will show that in mid-career Shakespeare was not only sympathetic to a figure such as Mrs Line, but well connected with the intellectual circles of Catholicism. Whether or not this was the case, documents from 1603 show that a Catholic writer, working in secret, was moved to reject the secular agenda of Shakespeare's plays - the playwright, then, pursued his own path in matters of conscience.

In the later 17th century, a story surfaced in the Cotswolds that Shakespeare had 'dyed a papiste', in other words, that he took the last rites of the old faith. If he did, it would reflect his sense of conflicting loyalties, typical of many of his generation.

The monument to William Shakespeare in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford © For the last of Shakespeare's days there are numerous documents bearing on his life in Stratford. The purchase of New Place was followed by several deals on land: evidently the writer was building up his holdings. He may have retired to Stratford after writing The Tempest in 1611: he gives Stratford as his address in a London court case in spring 1612.

The monument to William Shakespeare in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford © For the last of Shakespeare's days there are numerous documents bearing on his life in Stratford. The purchase of New Place was followed by several deals on land: evidently the writer was building up his holdings. He may have retired to Stratford after writing The Tempest in 1611: he gives Stratford as his address in a London court case in spring 1612.

Other documents show Shakespeare's involvement in a dispute between some rich landowners, the Combes, whom he knew, and a group of the rural poor. William seems successfully to have acted as an honest broker between the two sides - according to the notebook of his cousin, Thomas Green, where conversations with 'my cousin Shakespeare' are reported.

There are still, however, many riddles. In 1613, for example, as has already been mentioned, Shakespeare bought a large London house in the Blackfriars - but only after he had moved back to Stratford.

The burial register of William Shakespeare, 25 April 1616. By then he was a pillar of the local community © The last primary documents concerning Shakespeare are his will and the record of his death in 1616, on the date of his birthday, 23 April. He was a rector of his local church towards the end of his life, and as a benefactor he was allowed prime position in front of the altar for his own tomb, and for those of his family - where they still lie to this day.

The burial register of William Shakespeare, 25 April 1616. By then he was a pillar of the local community © The last primary documents concerning Shakespeare are his will and the record of his death in 1616, on the date of his birthday, 23 April. He was a rector of his local church towards the end of his life, and as a benefactor he was allowed prime position in front of the altar for his own tomb, and for those of his family - where they still lie to this day.

So there's a brief account, telling what has been found from some of the more interesting Shakespeare documents - from more than a hundred papers that name the poet. How will the new discoveries and reappraisals affect our view of Shakespeare?

Obviously these documents help set the writer in his time in a much more concrete, and human, way. Many questions, including the one concerning his self-effacing stance, may now have answers. His characteristic quality, his empathy - his feeling for the 'stranger's case' - for example, is all the more explicable in someone who came from an increasingly persecuted minority.

The world he represented with such affection - old England with its good and bad kings, old friars and holy women - is the world he had lost. More even than we could have guessed, in his own life he embodies the conflicts of his time, the cultural revolution of the Elizabethan and post-Elizabethan age. It remains true, however, as his friend Ben Jonson said, that Shakespeare 'was not of an age but for all time'.

Books

Shakespeare's Lives by Samuel Schoenbaum (Oxford Paperbacks, 1993)

Shakespeare: A Life by Park Honan (Oxford Paperbacks, 2000)

Ungentle Shakespeare by K Duncan-Jones (Arden Shakespeare, 2002)

In Search of Shakespeare by Michael Wood (BBC Worldwide Ltd, 2003)

New Worlds, Lost Worlds by Susan Brigden (Penguin Books, 2001)

Family Life in Shakespeare's England 1570-1630 by Jeanne Jones (Sutton Publishing, 1996)

Shakespeare's Birthplace: This half-timbered building in Henley Street, Stratford-upon-Avon, was bought by Shakespeare's father, John, probably in two stages (in 1556 and 1575). This is the house where Shakespeare and his brothers and sisters were born and brought up. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust completed the re-presentation of the Birthplace in April 2000. Rooms are furnished as accurately as possible to recreate the interiors as they might have been in the 1570s and include a glover's workshop.

Anne Hathaway's Cottage: Anne Hathaway's Cottage is in Shottery, a hamlet within the parish of Stratford but just over a mile from the town centre. It was the childhood home of Shakespeare's wife, Anne, the daughter of a yeoman farmer, Richard Hathaway.

Shakespeare Birthplace Trust: As well as Shakespeare material of international importance, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Records Office holds many thousands of records relating to Stratford-upon-Avon and the surrounding area. Anyone studying local history in Warwickshire and neighbouring parts of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, or tracing a family who lived here, is almost bound to find something of interest.

Michael Wood is the writer and presenter of many critically acclaimed television series, including In the Footsteps of...series. Born and educated in Manchester, Michael did postgraduate research on Anglo-Saxon history at Oxford. Since then he has made over 60 documentary films and written several best selling books. His films have centred on history, but have also included travel, politics and cultural history.

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.