From grand stately homes and public buildings to obscure graveyards and private homes, Britain's slave trade history can be traced in the local landscape around the country.

By S I Martin

Last updated 2011-02-17

From grand stately homes and public buildings to obscure graveyards and private homes, Britain's slave trade history can be traced in the local landscape around the country.

The geography of the British Isles, unlike that of the United States, doesn't at first sight appear to yield any clues to the country's slave trading past. There are no plantations, no plantation houses and seemingly little to suggest any connection between this country and the transatlantic trade in human lives.

Slavery appears as something that happened a long time ago and very far away: out of sight and out of mind. But a closer look at the built environment reveals that links to the slave trade are not only much closer than we realise, but also more numerous.

A square in Plymouth commemorates John Hawkins. A statue of Sir Francis Drake overlooks Plymouth Sound.

Few know of Hawkins' voyage to West Africa in 1562, in search of human cargo.

The story of how these mariners repulsed the Spanish Armada of 1588 is seen as a cornerstone of popular British history, yet few know of Hawkins' voyage to West Africa in 1562, in search of human cargo.

His delivery of 300 Africans as slaves to the Spanish Caribbean is generally credited as being the first instance of an Englishman engaging in the transatlantic slave trade. Hawkins' cousin, Francis Drake, would join him on a later slaving voyage to the African coast. Which story is remembered, and why?

Identifying and tracking traces of the slave trade on a local level will do much to illustrate the depth and nature of its impact on our cultural, social and economic history.

Harewood House, Leeds © When looking for traces of the slave trade, 'following the money' will inevitably lead to the most visible signposts of the wealth this business generated - the great country houses.

Harewood House, Leeds © When looking for traces of the slave trade, 'following the money' will inevitably lead to the most visible signposts of the wealth this business generated - the great country houses.

The discovery that an individual was a shareholder in the Royal Africa Company in the 17th century is usually an indicator that a significant portion of that family's wealth originated from the slave trade.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, a string of extraordinarily ostentatious properties were built or expanded on directly as a result of profits derived from the trafficking of people across the Atlantic, and the production of goods connected to their purchase and sale.

The more obvious houses, like Harewood, are already well-documented, but enquiring into the origins and connections of even the more obscure houses often produces interesting results. If the house in question is in the care of English Heritage or the National Trust, the property manager should be able to offer details of its ownership history.

The discovery that an individual was a shareholder in the Royal Africa Company in the 17th century (as was George Garth of Morden Park Hall, London), or that they sat on the Committee of West India Merchants in the 18th (like the Wedderburns of Inveresk Lodge) is usually a solid indicator that a significant portion of that family's wealth originated from the slave trade.

A perfect example of this phenomenon is the recently restored Danson House in Kent. It was built in 1764 for John Boyd, the son of the St Kitts planter Augustus Boyd. The Italianate villa was designed by Robert Taylor, and the garden by Capability Brown. Danson House was built to be a show home and a forum for displaying Boyd's growing collection of fine art, rare and antique books.

Statue of Edward Colston, Bristol © The profits from slavery were not only used to purchase property and seats in parliament, it also served to buy public sympathy in the form of good works and acts of baronial largesse.

Statue of Edward Colston, Bristol © The profits from slavery were not only used to purchase property and seats in parliament, it also served to buy public sympathy in the form of good works and acts of baronial largesse.

In Bristol, the name of Edward Colston is still associated with the schools and churches that benefited from his donations, rather than with the business of slavery from which he made his fortune. Roads are named after him and his statue stands on one of the many streets that bear his name.

Fortunes made in the Caribbean were central to the creation of the idea of the 18th century English country gentleman.

Similarly, Abraham Elton's ships regularly left Bristol's docks, bound for Africa with copper and glass that would be exchanged for human cargo. Elton soon found himself sufficiently enriched to make a gift of £10,000 to the coffers of George I, an act that ensured Elton's baronetcy. The family's legacy in the form of road-building, scholarships and health care seems to have eclipsed all memory of the origins of their wealth.

Fortunes made in the Caribbean were central to the creation of the idea of the 18th century English country gentleman. The countryside is littered with their decaying estates.

The gothic folly of Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire was built by William Beckford, heir to a family of planters. The scale of the projected building and its inevitable failure stand as a testament to the wealth and hubris of a family which left Beckford an inheritance of £1 million on his 10th birthday in 1770.

Less well known is Piercefield Hall and its 3,000-acre estate near Chepstow in Monmouthshire. In 1802 Nathaniel Wells, the son of a St Kitts planter, bought this property, designed by Sir John Soane and at the time the largest estate in South Wales.

In this he was no different from the other sons and daughters of the 'plantocracy' who were busy buying up country seats in the area. But Nathaniel was unusual because of his mixed heritage - he had a Welsh father and an African slave mother. Along with other British slave-owners, he was well compensated for the loss of his human property after the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

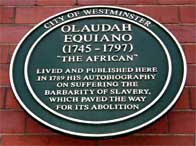

St Andrew's Church, Soham, where Olaudah Equiano married Susanna Cullen © The slave trade has also left its mark in more obscure places than the grand stately homes. Churchyards nationwide testify to the presence not only of enslaved Africans, but also a centuries-old community of free black people whose presence in Britain has been largely forgotten.

St Andrew's Church, Soham, where Olaudah Equiano married Susanna Cullen © The slave trade has also left its mark in more obscure places than the grand stately homes. Churchyards nationwide testify to the presence not only of enslaved Africans, but also a centuries-old community of free black people whose presence in Britain has been largely forgotten.

Since the early 16th century, black slaves and servants were popular in fashionable households. Some were given their freedom, many were not. Baptisms of slaves were not unusual and parish registers contain abundant references to the burials of black people in Britain, both enslaved and free, during the period of the transatlantic slave trade.

County or borough archives are a good place to start any search on this topic. Several local authorities, including Suffolk, Northampton and the London borough of Lambeth, have begun to catalogue the history of Britain's black population as found in their public records.

Independent researchers should note signs of adult baptisms, Graeco-Roman male names, racial epithets (in particular 'blackmoor', 'blackamore' and 'negro') and any hint of birth in either Africa or the Caribbean. A combination of two or more of these occurrences in records relating to any individual would indicate that they were black and possibly also a slave.

Baptisms of slaves were not unusual and parish registers contain abundant references to the burials of black people in Britain.

Slave graves can be found everywhere. A headstone at St Mary's church, Culworth, Northamptonshire, is in memory of Charles Bacchus, who died in 1762. He was an African servant to a local family. In the churchyard of St Martin's in Werrington, Cornwall, we find the final resting place of 'an African', Philip Scipio, who worked for Sir William Morice.

Scipio died in 1700. A well-tended gravestone at Sunderland Point, Lancaster, commemorates the short life of a child called Samboo, and reminds us of the young African children who worked as domestic slaves throughout Britain.

In stark contrast to these overlooked and often overgrown stones and inscriptions, monuments and memorials to the families of slave traders, planters and West India merchants are in great abundance in the most prominent places of worship. St Mary Redcliffe (appropriately found on Colston Parade, Bristol) and Bath Abbey are probably the most significant sites in this regard.

Some reassessment of national and local church history can also unearth interesting links. The Bishop's Palace at Exeter was restored under the direction of Henry Phillpotts (Bishop of Exeter from 1830 to 1869). The project was partly financed by the compensation that was paid to the bishop and his colleagues for the 665 slaves they were obliged to relinquish on Barbados when slavery was abolished in 1838.

These enslaved people lived on the Codrington Plantation on Barbados, and were owned by the Society for the Propogation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, part of the Anglican Church. The compensation amounted to £12,700 - over £1 million in today's money.

Part of the Rhinebeck Panorama, a watercolour of early 19th century London © The growth of the trade in people caused an increase in British shipping and commerce of all kinds. That slavery was central to this expansion is demonstrated by the rapid development of the docks in Bristol and Liverpool.

Part of the Rhinebeck Panorama, a watercolour of early 19th century London © The growth of the trade in people caused an increase in British shipping and commerce of all kinds. That slavery was central to this expansion is demonstrated by the rapid development of the docks in Bristol and Liverpool.

Carvings of African heads and elephants decorate Liverpool's town hall in clear reference to the source of the city's wealth. Between 1787 and 1807, all of the town's mayors were involved in the slave trade.

The memorial at St George's Quay is the only monument in Britain to the victims of the slave trade.

The popular focus on Bristol and Liverpool distract us from the fact that smaller ports also profited. Almost 15,000 slaves were carried in ships sailing from Whitehaven. More than 30,000 were carried by ships from Lancaster. Glasgow and Plymouth also had a significant trade in people.

Kevin Dalton's memorial to enslaved Africans at St George's Quay, Lancaster Docks, remains the only monument in Britain to the victims of the slave trade .

London's West India Docks opened in 1802. Described as the 'greatest feat of civil engineering since the building of the pyramids' and 'an undertaking which under the favour of god, shall contribute stability, increase and ornament to British Commerce', the docks were created at the request of the West India merchants' lobby, who wanted their own secured quays and warehouses to store sugar, rum and coffee from their Caribbean plantations.

The Maritime Museums of Liverpool and Lancaster and London's Museum in the Docklands have extensively catalogued the ways in which the slave trade changed Britain's waterfronts and the fortunes of all connected to them.

Further details, including a few examples of waterside slave history trails, are available on the Port Cities website.

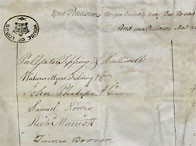

A pro-slavery petition of 1788 © Towards the end of the 18th century, the anti-slavery movement grew in size and scope. The parliamentary struggle was led by William Wilberforce, who is commemorated in the form of statues, memorials, monuments and inscriptions of all kinds.

A pro-slavery petition of 1788 © Towards the end of the 18th century, the anti-slavery movement grew in size and scope. The parliamentary struggle was led by William Wilberforce, who is commemorated in the form of statues, memorials, monuments and inscriptions of all kinds.

The history of the abolition campaign outside parliament is less well known. The movement to abolish the slave trade was the first genuine mass human rights movement in British history. Local anti-slavery groups flourished.

The numbers speak for themselves. In 1788 more than 100 petitions were sent to parliament in support of the cause. Manchester alone furnished 10,639 signatures. In 1792, 519 petitions were submitted in support of Wilberforce's proposed abolition bill. Manchester (with a population of 75,000) produced 20,000 signatures.

Membership of anti-slavery societies crossed all lines of class and sex (the latter much to Wilberforce's distress). Despite the fact that only adult male signatures on petitions were held to be valid, women such as Hannah More, and later Elizabeth Heyrick, proved to be some of the movement's most effective advocates and pamphleteers.

The Clapham Sect counted William Wilberforce, Henry Thornton, Zachary Macaulay and John Venn among its members.

The homes of many notable women, including Hannah More's in Blagdon, Somerset, and Elizabeth Pease's in Darlington, served as meeting places when public houses and municipal spaces were deemed inappropriate.

Quaker meeting houses throughout the country were frequently organisational centres for abolitionists, and Quakers were often at the forefront of the abolition movement. The Society of Friends has extensive records detailing their involvement in abolition, going back to its very beginnings in England in 1657.

The Methodists have similar records, though less scrupulously recorded. Methodist sites relating to abolition are nationwide and include Wesley's home in Ashford, Kent, and the Methodist chapel and museum at City Road, London.

The most prominent Christian anti-slavery group lived around Clapham Common. The Clapham Sect counted William Wilberforce, Henry Thornton, Zachary Macaulay and John Venn among its members, and their presence in the area is commemorated by English Heritage blue plaques and other signage. A great deal of research remains to be undertaken regarding the activities of less illustrious anti-slavery activists.

But most often, the physical legacy of the anti-slave trade campaigners hides from plain sight. Part of Kettering's coat of arms features a black man with a broken chain dangling from his wrist. This image symbolises the abolitionist work of a son of the town, the Reverend William Knibb, who campaigned against human bondage in Jamaica.

Other signs have a lower profile still. An anti-slavery arch can be found on the Paganhill estate in Stroud. Built by Henry Wyatt in 1834 to commemorate the passage of the Slavery Abolition Bill through parliament in 1833, this powerful monument is the only 19th-century anti-slavery monument.

Books

African History: a Very Short Introduction by John Parker and Richard Rathbone (Oxford, 2007)

Staying Power - The History of Black People in Britain by Peter Fryer (Pluto Press, ISBN:0 86104 749 4)

Britain's Slave Trade by S.I. Martin (Channel 4 Books (Macmillan))

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavas Vassa, The African (London 1789)

The Horrors of Slavery by Robert Wedderburn (London 1824)

Black & Asian Association Newsletter BASA, c/o ICS, 28 Russell Square, London WC1B 5DS

Specialising in the fields of Black British history and literature, S I Martin is a writer and researcher who has undertaken Black history projects for numerous organisations including English Heritage, the National Maritime Museum, the Museum of London, several London boroughs and the BBC. He is the author of the novel Incomparable World and the non-fiction title Britain's Slave Trade. He is the founder of the 500 Years of Black London walking and boat tours.

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.