Even the smartest of people can have preconceived ideas about certain aspects of life, whether they are places, objects or people. A very common preconception, even in today's society, is the one we have about people with disabilities. This summer I had the opportunity to work with some disabled adults on a camp in Virginia, USA; the experience altered many things, my cynical preconceptions being one of them.

Even the smartest of people can have preconceived ideas about certain aspects of life, whether they are places, objects or people. A very common preconception, even in today's society, is the one we have about people with disabilities. This summer I had the opportunity to work with some disabled adults on a camp in Virginia, USA; the experience altered many things, my cynical preconceptions being one of them. I had wanted to participate in the Camp America programme for a long time but never got round to it; last November however, I decided I had put it off too long. A lengthy process of applications, interviews, criminal record checks and general administration followed, until my papers were finally sent to the US for the placement process. Originally, I'd hoped my application would be accepted by a camp that catered for children. I waited and waited, but heard nothing. In March this year, frustration got the better of me. Seeing as I hadn't been placed on a camp, I decided to attend a recruitment fair in Manchester.

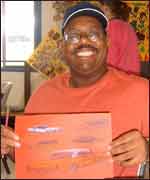

|

| "Camper who was excellent at drawing cars and drew 184 in the week that he was there. He had mild autism and was a fantastic artist." |

Trailing round the stalls, I was told, "We need lifeguards", or "Do you have any horse riding experience?" Me, horse riding? Yeah right! With much indignation about not being able to find a camp that appealed to me, I found myself in the cue for Civitan Acres, a camp based in Chesapeake, Virginia, that catered for adults with special needs and a range of disabilities.

Following a short interview, a grilling on why I wanted to work with adults with special needs (that I blagged because I desperately wanted to go to the states and was determined to get there anyway I could), which I answered with comments like: "It will be a challenge", "I've never done anything like this before and think it will benefit my character," yada yada yada, and I found myself placed - I finally had a job for the summer.

Working with people with disabilities of intellectual and physical proportions had never crossed my mind before. I had preconceptions about the kinds of disabilities I would be working with. In all honesty, I was bl***y scared. Would I be able to communicate with people who were non-verbal, or had profound mental retardation? Would I be able to understand the reasons someone with Autism did what they did? Would I be comfortable with lifting a physically disabled person, weighing 200lbs, onto the lavatory?

I didn't particularly want to bathe, dress or carry out hygiene routines with people who couldn't do it for themselves. I can barely look after myself, let alone anyone else, but over time, the idea grew on me. I wouldn't just be carrying out these kinds of tasks; I would be having fun with people that would fully appreciate the simple things in life. I would be making somebody's week just by being there for them, offering them a shoulder to cry on, playing in a swimming pool with them, or even just drawing pictures with them. I would be the making of their vacation, and whatever preconceptions I had about people with disabilities would have to be thrown in the trash.

My visa was successfully processed in May, my camp had been in touch with details of what to expect when I got there, and on 18th June, I found myself flying from Heathrow Airport to Norfolk, Virginia. Throughout the journey, my mind was inundated with thoughts about the coming weeks. I expected camp to be challenging, hard work and very demanding, but ultimately, I expected to have a ball, after all, how difficult could it be to entertain a few adults with special needs?

My first official interaction with the type people I would be working with came the week before camp actually began. We visited another special needs camp in Hampton, Virginia, called Sarah Bonwell. On entering the room my eyes filled with tears. There were so many amazing characters and all of them wanted to interact with these foreign faces that had come to entertain them. Throughout the day we participated in various activities, from face painting to bowling, but the highlight had to be the dancing. Not one camper remained seated and the effort they put in was just fantastic.

|

| "A camper enjoying getting his face painted by the clown. This was a major treat for the campers and they endorsed it with so much enthusiasm." |

Seeing how enthusiastic they became at the thought of a simple task or activity made me think about how much I take for granted. I don't think I can remember a time when dancing, bowling or face painting provoked such a euphoric feeling. Usually, I take these activities with a pinch of salt; as an everyday thing; something that occurs regularly (well, maybe not the face painting), but for the people we met that day, the activities were a release; a major part of their vacation, and something that obviously didn't happen that often. I went away from Sarah Bonwell with a sense of satisfaction, overwhelmed at how appreciative and loving these people were.

Camp work began the following week, and the preparation we had received as camp counsellors was very little. Although our interactions with the campers from Sarah Bonwell had provided us with a taster, it was nothing compared to the work we would eventually be carrying out. Our responsibilities were very weighted, and a camper's disability would determine how much or how little responsibility we had to take on. For example, if a counsellor was partnered with a camper who suffered from mild mental retardation, was able to get around and slept through the night, then their responsibilities would be limited; ranging from monitoring their actions to ensuring they were basically enjoying themselves.

On the other hand, a camper who was extremely low functioning and depended on a carer to feed, clothe, wash and dress them would require a lot more attention. Therefore, the counsellor's responsibilities would increase, with bathroom duties and dietary requirements being the major priorities.

Not only did we have to ensure that the campers were safe, satisfied and were having fun doing the activities we had planned (these included basketball, volleyball, baseball, swimming, drawing, painting etc) during the day, we also had to look out for them at night. Working at Camp Civitan was a 24/7 job, one where we had to be 100% focused at all times. With this in mind, it's easy to understand how my frustrations sometimes got the better of me. There were times when I felt the only solution was to walk away from an awkward position and not go back. There were times when my campers became so reluctant to participate I just wanted to cry. There were times when showering and assisting with toileting my campers became so inhumane that I wanted to punch something, lash out and leave. There were times when I took my frustrations out on my fellow counsellors, or times when I secluded myself from group activities during our weekends of free time...

More to come from Amy Farnworthwill she be able to survive at Camp Citivan...?

This article is user-generated content (i.e. external contribution) expressing a personal opinion, not the views of the BBC West Yorkshire website.