Bonkers banks

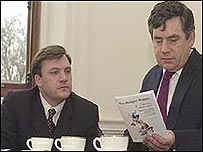

I’ve spent a disproportionate amount of time recently talking to the chaps who run our biggest banks. And in their relationship with government, they are going through a very interesting phase. Having for years been persuaded (correctly) that the chancellor, Gordon Brown, was out to get them, they now believe (more-or-less correctly) that he – and his minister for the City, Ed Balls – have fallen in love with them.

Yup, the new Brown/Balls consensus is that the banks are exemplars of Britain’s economic future, a “knowledge” industry where the UK has a competitive advantage. They have shed their angst that the banks might be operating a cosy oligopoly in those bits of their businesses which serve individuals like you and me and also small businesses (or what’s known as retail banking). For the Chancellor and his brainy consigliere, the banks are to be charmed not harmed.

Yup, the new Brown/Balls consensus is that the banks are exemplars of Britain’s economic future, a “knowledge” industry where the UK has a competitive advantage. They have shed their angst that the banks might be operating a cosy oligopoly in those bits of their businesses which serve individuals like you and me and also small businesses (or what’s known as retail banking). For the Chancellor and his brainy consigliere, the banks are to be charmed not harmed.

But here’s what irks the banks. Just when that lot in the Treasury have become chums, another part of the public sector – the regulatory side – is devoting all its energy and resources to biffing them. And it’s true that over the past few months there has been a baffling number of competition enquiries into various aspect of banking, not to mention a Financial Services Authority probe into whether specific banks and other financial institutions have been mis-selling payment protection insurance (policies that provide cover against an inability to repay a personal loan).

So here’s where I verge on acquiring some sympathy for the banks: the banking market in the UK is more competitive than it is in much of the rest of Europe; yet it’s the UK where the regulators are most aggressive in promoting more competition. For someone like me, there’s no such thing as “too much competition”. But there is a significant cost for the banks in complying with the non-stop requests for information and evidence from assorted watchdogs.

That said, the banks always succeed in alienating me at the last by the sheer silliness of their main arguments against the competition probes.

To remind you, there are two particularly resonant investigations: one by the Competition Commission into whether there is a proper transparent competitive market in payment protection insurance (PPI), which is additional to the FSA enquiries; and an initial information gathering exercise by the Office of Fair Trading into whether the banks levy excessive penalty charges on current account customers who borrow beyond agreed overdraft limits.

The banks’ contention in both cases is that these issues are sideshows: that the big and relevant facts are that current account services in the UK are relatively good value (in fact notionally free to most of us) and that personal loan rates are very attractive.

As it happens, I think they are probably right about what most of us pay for current accounts and loans. By international standards, British consumers typically receive their personal banking services (current accounts and loans) at a pretty good price.

But here’s where the banks’ defence goes a bit bonkers. They say (in private) that the sine qua non of free banking is the right to levy steep charges on the fools, knaves and unfortunates who breach their agreed banking limits. And the underpinning of relatively low personal lending rates is the right to stitch up customers on the insurance policies that often accompany the loans. Now, they don’t put it quite like that – but, believe me, this is the inescapable implication of their representations.

Their apparent conviction is that they can only make a decent return on capital from retail banking through muddying the water when it comes to precisely how they generate revenue.

They seem to believe that most of us would never pay them a fair price – whatever that means – for the current account services we use or for the loans we take out. So we’ve got to be subsidised by those who breach overdraft limits or by those who don’t mind paying too much for loan insurance.

Now obviously none of us would volunteer to pay more for any services. But standing back from our personal preferences, a market that functions with this degree of hidden cross-subsidy feels profoundly unhealthy to me.

It’s vital to all our prosperity that the banks make a proper financial return. But for that to depend on the ignorance, misfortune or negligence of a sizeable proportion of their clients can’t be satisfactory, sensible or sustainable. What do you think?

By the way, the FSA is running the banks a close second for its sheer silliness. Yesterday it fined GE Capital Bank £610,000 for PPI sales breaches. But that’s probably a fraction of what its parent company, the mighty General Electric of the US, spends in just a few days on flowers in its offices. In terms of overall group profits ($20.7bn after tax in 2006 from revenues of $163.4bn), it’s not even a rounding error, it’s the equivalent of that 20p piece that dropped down the back of the sofa which nobody can be bothered to fish out.

Of course, GE doesn’t like being ticked off in public. But guess what? I think it’s already over it.

For shareholders in BA, the big question is therefore whether the dispute which ended yesterday will make it easier or harder for the current chief executive, Willie Walsh, to respond to the intensifying competitive pressures in his industry. Now for all the talk about consensus and compromise in the aftermath, if I were a trade unionist I would be feeling pretty content. There was overwhelming support for strike action from cabin crew, the company has made concessions in the way it manages sick leave, there'll be an above-inflation pay settlement this year and differentials between the different vintages of cabin crew employees have narrowed.

For shareholders in BA, the big question is therefore whether the dispute which ended yesterday will make it easier or harder for the current chief executive, Willie Walsh, to respond to the intensifying competitive pressures in his industry. Now for all the talk about consensus and compromise in the aftermath, if I were a trade unionist I would be feeling pretty content. There was overwhelming support for strike action from cabin crew, the company has made concessions in the way it manages sick leave, there'll be an above-inflation pay settlement this year and differentials between the different vintages of cabin crew employees have narrowed. It's entertainment and soap opera too. Last week's ousting by the world's biggest bank, Citicorp, of a high-flying executive, Todd Thomson - after he shared a private jet with a glamorous US business journalist,

It's entertainment and soap opera too. Last week's ousting by the world's biggest bank, Citicorp, of a high-flying executive, Todd Thomson - after he shared a private jet with a glamorous US business journalist,  Now last week, the eminences of British private equity were out in all their pomp and finery at the most glittering of parties held in London's magnificently refurbished Roundhouse. Only rarely in the history of this nation can so many stupendously wealthy individuals have been gathered in one place. Many of those present were worth many tens of million pounds each, some worth comfortably more than £100m. According to a banker, the collective net worth of those at the do was more than £10bn.

Now last week, the eminences of British private equity were out in all their pomp and finery at the most glittering of parties held in London's magnificently refurbished Roundhouse. Only rarely in the history of this nation can so many stupendously wealthy individuals have been gathered in one place. Many of those present were worth many tens of million pounds each, some worth comfortably more than £100m. According to a banker, the collective net worth of those at the do was more than £10bn. Inevitably, therefore, private equity hasn't endeared itself to the trade union movement. And outside the Roundhouse last Wednesday night were protestors from the GMB, who've been targeting one of the UK's leading private equity houses, Permira. The GMB has been trying to embarrass Permira over job cuts at Birds Eye and the AA, two companies it controls (Permira shares ownership of the AA with another private equity house, CVC).

Inevitably, therefore, private equity hasn't endeared itself to the trade union movement. And outside the Roundhouse last Wednesday night were protestors from the GMB, who've been targeting one of the UK's leading private equity houses, Permira. The GMB has been trying to embarrass Permira over job cuts at Birds Eye and the AA, two companies it controls (Permira shares ownership of the AA with another private equity house, CVC). The move into broadcasting was a big one for me, because for the previous 24 years I’d been a print journalist. My previous roles have included financial editor of the

The move into broadcasting was a big one for me, because for the previous 24 years I’d been a print journalist. My previous roles have included financial editor of the  I'm

I'm