Clown Prince of bloggers takes on Italian politics

- 14 Apr 08, 02:25 PM

With Italy's elections complete, does the domination of the media by the political elite distort the debate, and will the internet change things?

I find one side of the coin in Milan, at the heart of the estate where Berlusconi made his first serious money.

Milano 2 is a suburb of luxury flats, ponds and trees, restaurants and a hotel. And a TV station. His first in what grew into an unrivalled media empire.

I am here to meet Emilio Fede, a short, well-tanned man with greying hair, a famous face on Italian TV since the 1950s.

He is a newsman more on the model of the old American news anchor than the British presenter. He’s the boss here. He doesn’t just read the main bulletin at seven in the evening. He decides what’s in it and all the other bulletins of TG4.

He’s editor-in-chief of the first TV station in Berlusconi’s now vast media empire.

Mr Fede is anything but impartial. He tells me not only that his friend Mr Berlusconi is a caring man, a man of the people, who has the answer to Italy’s problems but also that he brought the Cold War to an end.

Goldfishing

He is a fan, and the news reflects that. The day I am in the studio, the report on the opposition’s activities features just one politician talking in an interview.

But you don’t hear his words. He is, in TV parlance, goldfishing: you can see his lips move but only hear the reporter’s words. The report on Mr Berlusconi’s day has a rather long clip of him speaking.

After our interview, several uneasy Italian journalists suggest I must find it rather odd to discover a TV editor who supports one side so strongly.

Not really, I‘ve interviewed enough British newspaper editors for precisely the same reason: to get an intelligent informed, but partisan view.

That all broadcasters, even ones that don’t harvest a licence fee, are legally bound to be impartial in the UK, but newspapers are not, could be seen as a cultural quirk.

But it means that no-one in Italy seriously strives for objectivity.

Journalists are still organised in a guild, set up by Mussolini to control the press.

Before you are allowed to write a single article, you first have to have a sponsor within the industry, and then pass an exam sat in Rome, using an old-fashioned typewriter.

If the big organisation representing mainstream Italian journalists doesn’t even acknowledge the existence of the technology that has been dominant for the last 20 years, it’s not surprising that some see the internet as a way around the dead hand of an old elite.

Beppe the blogger

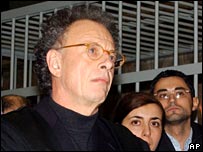

I go to Genoa to meet the man behind a blog whose aim is to clear the current political class out of power.

Beppe Grillo’s online comments were voted by Time Magazine’s readers as the world’s most interesting political blog.

Beppe Grillo is, I guess, in his fifties, a mass of wavy curls more salt than pepper and a neat beard framing his engagingly impish face.

An irrepressible performer with political clout, he’s the organiser of a rally with a very direct message to Italy’s political elite. It was called "F-Off day”. It drew a crowd of 80,000.

What amounts to political censorship cost him his job in 1987. He is a standup comic, and was perhaps the most popular comedian on Italian TV.

But then he made a joke about the then ruling party, the Socialists, being corrupt. The show’s host walked off stage, the doorman wouldn’t look him in the eye and he never appeared on TV again, barred by both the state and Berlusconi’s private empire.

Even after a massive bribery scandal brought about the collapse of the Socialist party, he didn’t get his job back.

Not that it did him any harm. We are talking in his large study and sitting room taking up the whole bottom floor of his rather wonderful villa perched on a hillside overlooking the sea, just outside Genoa.

He fills any theatre he plays to and is one of the most influential alternative political voices in Italy. He takes on big companies and says things about politicians that leave him embroiled in dozens of court cases.

The first protest, or V-Day from its Italian name, demanded that the whole political elite, but particularly politicians with criminal convictions, should leave the political stage.

Media reform

Day Two demands a reform of the media.

“We are enraged, we have a feeling of hopelessness,” he says.

“We have a parliament full of felons. We have a hit-parade of crooks in our parliament, making laws for Italy.

“The current political class has to go – en masse. Then we’ll start again with young people – in their 20s and 30s. And then via the internet we’ll start to create what you might call the virus of a new beginning from the bottom up.”

He says the internet is key to this new beginning.

“We have seven television networks, and three newspapers that inform public opinion. And these are all in the hands of the banks, industrialists and politicians – and they all back each other up. And, without their say so, nothing happens.”

He says Italians are in a comatose state, with the media in control.

“And this is why our next ‘F-Off Day 2’ will focus on the media. We have to stop these millions of euros of public money being handed over to the newspapers; we’ve got to get rid of this ‘guild of journalists’, and we have to get rid of a law that allows Berlusconi, whom today we also refer to as Asphalt Head, to own three TV networks and 10 newspapers, and then become prime minister.”

I question how much impact this control of the media has.

After all I have just had a lively lunch with an Italian family arguing furiously about which way they should vote.

The newspapers are full of highly intellectual analysis, probably of a higher quality than in Britain. The party system means voices that would be excluded in Britain, from the hard left and hard right, are heard in Italy as well as the views of greens of various shades, libertarian socialists and of course the mainstream.

But this is not quite what he means. He is talking about something much more basic. The simple facts.

'Tittle tattle'

“Here in Italy we don’t know the whole truth. We know tittle tattle. What we’re told isn’t false, it’s verisimilitude.

If you have a criminal mind, you’ll be successful in this country. If you don’t, you won’t. That’s the problem with this strange country.”

He gives an example. A politician in the last government was closely linked, he claims, with a business over which his ministry has control. Now I am not going to get into specifics because I do not have the time to check out a claim that would be libellous if not true.

And Italian journalists are likewise scared off by the law and the willingness of politicians to use it. But there’s a difference.

In Britain, if such an allegation was made, it would be instantly checked out and, if true, it would dominate the headlines for days. I am not saying the media in Britain is perfect, indeed it may be blind to many things, but it is an effective check on serious financial scandal.

Given the litigious nature of Italian politicians, few people will put their heads above the parapet.

My most frustrating interview on this trip was with former magistrate Gherardo Colombo about a book he has recently written on a most fascinating subject, the relationship between Italians and rules.

His sound, if basic, theory is that in Italy people at the top see only their privileges and people down the pyramid only their responsibilities.

I have no doubt he is a very brave man. He would have to be to have conducted the investigations into organised crime that he has presided over.

But he does not want to talk about the election, about Berlusconi, about how his theories affect political life in Italy.

This of course is his right, and he may have reasons I can’t guess at. But I suspect after a time it just becomes too much hassle, too wearying.

This worries me. Getting people to think through to conclusions themselves; by stirring up academic debate without spelling out the obvious is what dissidents have to do in dictatorships.

Clearly Italy is anything but, but sometimes you wouldn’t know it from people’s behaviour.

Big fish

Beppe Grillo, ever the standup comedian, mimes munching a large fish as he answers my question.

He says that, just like people who only have ever tasted farmed fish, Italians have forgotten the taste of real democracy.

“We no longer have a proper idea of what democracy is all about. We no longer have proper freedoms. We know nothing about anything.

“I’d say to you that if you know of British companies that want to come here, they can come – because things are simple here. They can submit false accounts, do insider-trading and the like. The problem with this country is that we don’t know the whole truth.”

Back at his computer, Beppe Grillo shows me his plans for V2 Day on his blog.

People can add their avatars to the virtual protest and a bunch of cartoon characters march across the screen to tell, not the politicians this time, but the media to get lost.

Are they right? Can they win?

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites